3. OPen Virtual and distance learning for teachers

advertisement

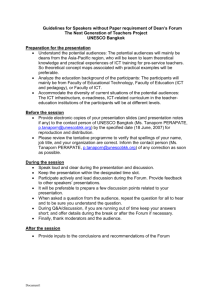

Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers APA-sherri APA-joke REV CHK Revised 200607 NOTES FROM THE EDITORS: - - - Green highlights as well as comments need the attention of the author; yellow highlights require attention from the Handbook editors; Be sure that your file – when you open it - also shows the comments! This is a nice chapter; it provides enough background literature to illustrate concrete examples of IT use in teacher education; Check on terminology used: you easily use different terms for the same things; either make this clear to the reader or use less different terms. (e.g. 1. virtual learning environment – e-learning platform – ICT-based(supported) learning environment)online learning environment-open learning environment and 2. e-learning-online learning) Add a small concluding section at the end of the chapter with the aim to summarize and suggest steps for future research and developments. Please review our comments/changes and revise your chapter accordingly. We did not yet check the references (complete/APA); we might come back to you when necessary. ONLINE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT FOR TEACHERS Márta Turcsányi-Szabó, turcsanyine@ludens.elte.hu Eötvös Loránd University, Faculty of Informatics, Department of Media & Educational Informatics 1117, Budapest, Pázmány Péter Sétány 1C., HUNGARY tel: (+36 1) 381-2298, fax: (+36 1) 381-2140 ABSTRACT The most effective way of spreading and updating professional development for teachers can be done with the use of virtual learning environments. They provide ease of delivery, flexibility for usage of resources, technology to support collaborative work and emergence of learning/teaching communities that can further help each other in their common tasks. Technology use is a basic feature of online professional development, since it provides the technology of delivery as well as effective means of learning. Therefore, professional development has to consider the use of information and communication technologies as its main priorities when transforming teacher education into an effective process. Education also 1 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers has to take into consideration the change in the forms of learning, turning away from more formalised school settings into various forms of informal modes of learning, thus the design of learning objects have to satisfy a more flexible use of materials within different contexts. KEYWORDS Continuous professional development, Europe, Hungary, initial teacher education, learning objects, School networks, virtual learning environments 1. INTRODUCTION The world is facing an acute and growing shortage of teachers. Besides, many teachers work in overcrowded classrooms where frontal teaching and rote learning makes it difficult to motivate children to learn in school, thus new teaching methods and strategies are needed to change teacher practices. Technology can create virtual learning environments, which on the one hand provides motivating learning situations as well as allows to quickly reach remote areas in need and provide a flexible training environment for all participants (UNESCO Teacher Education Web site, n.d.). Online education originated from Distance Education as technology penetrated deeper into the method of delivery and communication. Distance Education refers to the delivery of education to students who are not physically at the training institution itself. Delivery of learning materials are provided through printed or electronic media or e-learning/onlinelearning technology and communication between teachers and students can be managed through technology that allows asynchronous or synchronous communication. In case any amount of on-site presence is required, then the learning mode is rather described as blended learning, and in case more of the subjects and objects of learning are connected through technology, then the learning mode is described to be facilitated through virtual learning environment. In terms of prefix use, one can trace the path of development and be able to distinguish between D-learning (Distance Education), E-learning (Technology Enhanced Learning), M-learning (Mobile Learning) where students do not need to keep location and use mobile or portable technology (Wikipedia – Distance Education Web site, n.d.). However, e-learning is not a synonym of online learning. While e-learning requires the fluent use of enhanced technology in itself as it is performed through emerging technologies, delivering knowledge and information through multimedia content and internet resources, it is not necessarily performed online, but can well be utilised in a face-to-face classroom situation as well. The essence of online learning – in addition – is in its collaborative nature, that simulates face-to-face classroom activities by providing virtual learning environment (e.g. Moodle, BSCW, Blackboard, WebCT), collaborative teaching/learning environments to share and communicate online (by using e-mail, mailing lists, chats, forums or videoconferences), use virtual laboratories to perform experiments and facilitate assessment by application of automatic assessment tools, portfolios and web-logs. It is evident from the above, how technology plays a deterministic role in mode of education in exactly the same way as technology penetrates the everyday lives of business and leisure activities. Even though, the call of time has urged technology to make an immediate penetration into business, a delayed impact on the leisure market is observed, and a far more retarded emergence within education can be experienced. Technology, as it is, seems to be an 2 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers unproved obstacle for schools rather than an enhanced facilitator for learning. Therefore, teacher education of our present days has to exert distinct efforts to show and prove good practices and integrate Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) into the everyday teaching processes. The main problem might originate from the fact that the majority of teachers practicing today have learned the teaching profession through books and in face-toface, frontal teaching situations and have little chance within their own learning experiences in using technology to provide self-proof. Technology progresses rapidly, so Initial Teacher Training (ITE) cannot prove to be enough, but Continuous Professional Development (CPD) has to deal with new emerging technology, context and methods, in which the use of ICT must have an outstanding role. Therefore, this chapter deals not only with online professional development of teachers in general, but specifically concentrates on the issue of using ICT tools and e-learning materials on the road as it both facilitates the learning process of teachers as well as provides resources for enhanced learning in schools. Besides official training programs, the case of providing online curriculum materials is highly important. Research in the UK claims that the nature of ICT is fundamentally antipathetic to the culture of the school and highlights the dissatisfaction towards the educational system, which is leading increasing numbers of parents in the USA and the UK to remove their children from school and educate them at home, using the services of Internet-based providers of educational materials (Somekh, 2004). Of course one can only understand the problems fully by examining the pedagogy related to ICT usage – this chapter cannot deal with this rather extensive and very important issue – but one should be guided on with the evidence that new affordances provided by virtual learning environments require teachers to undertake more complex pedagogical reasoning than before in their planning and teaching (Webb & Cox, 2004). There is also evidence that online projects make great impact on teachers and thus act as professional development side-effect, especially in relation to the use of new technologies (Turcsányi-Szabó et al. 2006; also see 6.7 of this Chapter). The assertion claims, that classroom activities are the catalyst for professional growth as classroom behaviours are determined directly by teacher beliefs on which the experiences can make impact after reflections on evaluations of success of new practices (Fisher, 2003). Moreover, classroom observations suggest that technology integration is governed by six key elements (relevance, recognition, resources, reflection, readiness and risk), which changes pedagogic practices and allows teachers to take ownership of their professional development (Rodrigues, 2006). Whereas the design of virtual learning environments and activities also require the implementation of an integrated approach to pedagogy and technology which recognizes how these activities, communities and environments represent, transform and encourage a virtual extension of a face-to-face classroom (Richards, 2006). This chapter first examines Initial Teacher Education (ITE) and Continuous Professional Development (CPD) within Europe and beyond, discusses virtual and distance learning possibilities offered for teachers and highlights case-studies from all over the world. Then it elaborates on trends of knowledge delivery and revisits lessons learned in Teacher Education (TE) within the region of Asia and the Pacific. Finally, the issues are specifically examined within the example of Hungary. 2. TEACHER TRAINING IN EUROPE AND BEYOND The governments of all European countries share the awareness that teachers’ professional development in ICT for education is a key factor in school innovation. However, they have 3 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers adopted different approaches to the question, ranging from very decentralised and autonomous initiatives to very structured systems (Midoro, 2005). 2.1. Basic skills in the use of ICT within ITE An increasing number of students already acquire ICT skills before entering higher education, which has been mastered either at school (primary or secondary) or autonomously, independent of their education path. Thus, in some institutions basic ICT skills are already considered as a prerequisite in higher education. But, since the situation is often quite heterogeneous, most institutions also offer (mandatory or optional) courses for developing basic ICT skills on different levels. In some countries like Iceland and the UK, institutions offer their ICT courses online, so trainees acquire a certain implicit knowledge concerning both the used technology (CMC systems, virtual learning environments, etc.) and the processes of online communication and collaboration. Unfortunately this does not mean that future teachers are also able to use ICT effectively in the classroom. Thus, institutions in Europe are following two main kinds of approaches in order to develop the specific competencies needed: to use new technologies for supporting learning processes within specific subject areas, and to master methods and tools for designing and using virtual learning environments (Midoro, 2005). 2.2. Approaches of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) In some countries, teachers’ professional development is a natural continuation of ITE and in other countries, there seems to be no continuity between ITE and CPD. For example in Belgium, Germany, and Sweden, public or certified private bodies autonomously propose courses in ICT for education addressed to in-service teachers, while in Greece CPD is completely organized and managed at a national level by a single central body. In some approaches centralised and decentralised aspects are merged together and this can occur with different levels of intensity (Midoro, 2005). Often, courses are delivered blended, allowing face-to-face lessons as well as online lessons with collaborative activities (see also National Reports of Italy, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Greece, Portugal, Germany, and Spain (@Teacher - National Reports Web site, n.d.). In many countries qualities of teachers are more often measured through competencies within their professional functionality (Resta, 2002; Midoro, 2005) which of course depends on local principles and strategies employed in planning as well as the surrounding community (Majumdar, 2005). 3. VIRTUAL AND DISTANCE LEARNING FOR TEACHERS Evidence shows that distance education in its various forms can work and if well-designed can be educationally legitimate. It has been applied to the education of teachers and has been shown to be effective on a number of measures, for example the number of students enrolled, outcome, cost, etc. (Perraton et al., 2002). 3.1. How to build virtual and distance learning for teachers In terms of cost per student, distance-education programmes have often shown advantages over conventional programmes (Kvaternik, 2002). UNESCO is very actively publishing experiences in TE all over the world and provides guidelines especially for developing 4 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers countries to gain knowledge on building effective institutions (UNESCO – Teacher Education Web site). Regional and country overviews, projects, online resources, and more valuable information can also be accessed for use. (UNESCO Bangkok – ICT in Education Web site, n.d.) 3.2. Models for Online Professional Development Based on Tinker’s taxonomy, four models of online professional development can be identified (Haddad & Draxler, 2002): the course supplement model, complements traditional face-to-face teacher training; the online lecture model, uses primarily one-way delivery of high-quality content and some orientation from instructor; the online correspondence model, uses fewer resources, but offers increased personal contact; and the online collaborative model, emphasizes on collaboration activities among participants through high technology and expert facilitation. Besides normal universities all sorts of formal and informal form of education exists, which often require high levels of online presence. 3.3. Types of Institutions Open Universities: A substantial portion of open university students are seeking regular university degrees, and another significant portion are engaged in lifelong learning, advancing their knowledge and skills for occupational, family, and personal purposes (Haddad & Draxler, 2002). Examples: The Open University Web site (http://www.open.ac.uk/), China TV University Web site (http://www.crtvu.edu.cn), Indira Gandhi National Open University Web site (http://www.ignou.org/index.htm). Virtual Universities: Incorporates a variety of institutions that may be classified as megauniversities, open universities, and dual-mode universities, and whose primary programs are at a distance, as well as those that may be referred to commonly as virtual universities (Haddad & Draxler, 2002). Examples: Peru’s Higher Technological Institute Web site (http://www.tecsup.edu.pe), and African Virtual University Web site (http://www.avu.org). Community tele-centres: In developing countries on every continent, public ICT access centres are springing up and bringing information from around the world to communities, generally referred to as tele-centres. They vary in the clientele they serve and the services they provide. All models are useful. But so far, the version designed specifically to achieve education and development goals – including affordable access and training for students, teachers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and other social development agents – is the most likely to ensure access for targeted, low-income populations (Haddad & Draxler, 2002). Their publication mentions examples from Benin, Ghana, Asunción, and Bulgaria. Thus, learning can take place in various types of formal and informal institutions of learning, where the essential element can be viewed as the access to motivating learning materials that allow flexible use in a lifelong learning scheme. The design of such learning materials is crucial, as flexibility also means the use of the same learning elements in different contexts. This will be dealt with in the next section. 4. TRENDS IN KNOWLEDGE DELIVERY 5 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers 4.1. Trends in Content Development – Learning Objects and Repositories There is a need for standardised systems that can catalogue, store and retrieve content in ways that enable users to access and organize it for their particular purposes as well as sharing it institutionally, nationally, and internationally. There is a great deal of effort being expended around the world on the development of such systems – ones that will standardize the development of resources Learning Objects (LOs), catalogue them (metadata) and store them in repositories (Glen & Farrel, 2003). Examples: The eduSource project Web site (www.edusource.ca/english/what_eng.html) and Merlot Web site (www.merlot.org/Home.po). The use of LOs in education – especially elementary and secondary education – is still in a starting stage and thus a lot of lessons still need to be learned in order to make them have an innovative impact on the learning process. McCormick and Li (2006) evaluated the use of European LOs. Their findings indicated that teachers were generally unhappy about the fit of LOs to the curriculum, though they are able to superimpose their own pedagogy on any LO and found their granularity and interoperability characteristic to be the most significant in their usefulness. LOs themselves do not guarantee high-quality learning performance and meaningful learning activities, but they require carefully designed learning environments and instructional arrangements (Nurmi & Jaakkola, 2006a). The teachers’ role in organising, structuring and guiding the whole process is crucial, whereas the design of LOs have to take into consideration a pedagogical context which is less task-centred, but more idea-centred (Ilomaki et al., 2006). In fact, the promises of LOs can only be fulfilled when they are used according to the principles of contemporary learning theories - viz. engaging students in active knowledge construction and meaning making (Nurmi & Jaakkola, 2006b). Thus, frameworks for knowledge management and appropriate environments need to be put in place to activate LOs to their full potential and allow emergence of online communities of users. 4.2. Trends in Portal Development Butcher (in Glen & Farrel, 2003) describes three types of portals currently available, emphasising that, in many instances, these services are merged in a single portal: Networking Portals, provides access to various individuals to tools and facilities; Organizational Portals, constructed by organisations whose core business is to deliver educational materials; Resource-based Portals, provides access to various educational resources online. To create successful online communities, strong social and intellectual benefits that cannot easily be accomplished in face-to-face communication must be realized – and innovative technology must be a part of that overall package. Collaboration with, or sharing of, resources can be helped by facilitating sharing and communication in communities governed by common work and purposes. Building communities of practice has become a major theme of educators’ professional development research and practice since it enables teachers to promote collaboration, increase idea creation, solve problems in time- and cost-efficient manners, and, therefore, foster social capital. Example: TeacherBridge project Web site (http://teacherbridge.cs.vt.edu/). When the learning task itself is the learner’s task, when the situation is under the learner’s control, and when the activities of learning are personalized by that learner, participants are motivated and educational outcomes are greatly enhanced This approach allows teachers to get started on projects as quickly as possible, a behaviour which minimalist theory explicitly 6 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers encourages: people can easily learn by doing with concrete examples, not by being told how to do things (Kim et al., 2003). Examples: AskERIC Web site (http://askeric.org/About/), Knowledge Finder Web site (http://colfinder.org/public), and UNESCO Community of Practice in Curriculum Development Web site (http://www.ibe.unesco.org/COPs.htm). It is not only professional development that such portals can support, but also the target areas of public education with all other sorts of emerging informal learning modes. 4.3. Trends in learning modes Open Schools – The models that have evolved in the primary and secondary education sectors as a result of the use of distance education methodologies often use the label Open School (Glen & Farrel, 2003). Examples: Open School BC Web site (http://online.openschool.bc.ca/). School Nets – A portal managed by local or international stakeholders, providing learning materials and activities for both institutions and individuals on a broad level (Glen and Farrel 2003). Examples:: SchoolNet Canada Web site (www.schoolnet.ca), European SchoolNet Web site (www.eun.org or www.eschoolnet.org), SchoolNet South Africa Web site (www.school.za), SchoolNet Africa Web site (www.schoolnetafrica.net), and World Links for Development Web site (www.worldbank.org/worldlinks). The question remains: how well can these trends and experiences be utilised on a larger scale, bloom within different cultures and language areas, serve varieties of country policies and be adaptable in underdeveloped regions as well, where the greatest need for teaching and learning is required. It is worth examining the factors that lead to effective implementations. 5. LESSONS LEARNED IN ASIA & THE PACIFIC REGION 5.1. Curriculum and Content Development A synthesis of lessons learned provides the basis for the development of tools and blueprints to guide policy and programme improvements for the appropriate use of resource to support the integration of ICT in education, based on the experiences of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, with respect to curriculum, pedagogy and content development in the integration of ICT in education (UNESCO, 2004a). 5.2. School Networking The decision to establish a SchoolNet must take into account wide-ranging considerations, as can be seen from experiences of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, with respect to SchoolNet-related infrastructure and connectivity (UNESCO, 2004b). Further country overviews can highlight different aspects in relation to (I)TE programs in Asia and the Pacific at UNESCO Bangkok – Regions and Country Overviews Web site (http://www.unescobkk.org/index.php?id=783) Private enterprises also provide support and very successful initiatives that spread rapidly all over the world. A very good example is Intel, which offers free professional development to K-12 educators, focused on enhancing education with technology and student-centred 7 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers learning approaches (Intel Teach http://www97.intel.com/education/teach/). to the Future project Web site - There are of course many different success stories. The International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP), among others, holds a Technical Committee of ICT in Education that operates a web page where the different country profiles contain basic documents for planning at national level, national educational networks, and the best educational projects that are running in the country at present (IFIP TC 3 Country Profiles Web site - http://www.ifip-tc3.net/rubrique.php3?id_rubrique=18). 6. THE CASE OF HUNGARY 6.1. Teacher Training In Hungary, concerning ITE, one has to consider that Informatics is a compulsory subject from elementary 5th grade onwards since 1998 (Turcsányi-Szabó & Ambruszter, 2001). Thus specialised Informatics teachers are trained throughout the country to deliver the subject on a high level, both at elementary and at secondary schools. There were four universities in Hungary that were involved in the training of secondary school informatics teachers and five colleges that were involved in training elementary school teachers so far, which are now in the process of change due to the Bologna process. Concerning CPD, all teachers in Hungary have to undergo 120 lesson hours of in-service training once every seven years. Thus courses offered all over the country in Universities, Teacher Training Colleges, and Institutes for Professional Development, concentrate on new competencies to be mastered according to the requirements of present time. 6.2. Infrastructure In 1994, the Hungarian Ministry of Education initiated a nation-wide project financing Internet facilities for all schools, training and content for school-work facilitating connection to institutes bearing public collections and it’s access as well to Hungarian nationals outside the country (Turcsányi-Szabó & Ambruszter, 2001). The project financed the following topics: The establishment and operation of 64Kb communication lines for schools allowing unrestricted Internet access. Equip all schools (all secondary schools till 1st September 1998, all elementary schools till 2002) with Internet-ready multimedia lab. Develop content for educational materials accessible via Internet that would help school work: supplementary course materials, assignments for individual work, multimedia and Internet introductory kit, monthly newsletter, musical resource kit, and recently accessible research materials. Facilitate bi-directional data exchange via co-ordinated data-bases that could be accessed nation-wide. The ministry also financed the establishment of reference centres and training centres for teachers, where courses would be held in the following levels: Basic Internet use: for all teachers that are not specialised in informatics. Educational Informatician: a high degree for non informatics specialists. School ICT advisor: for those bearing a middle degree in computer science. 8 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers 6.3. Distance Education Considerable efforts have been made in Hungary since the early 1990s to establish a distance education system for taking advantage of the increasing ICT use. As a promoter of the development the National Council for Distance Education (set up in 1991, NCDE Web site http://www.ntt.hu) coordinated large Tempus and PHARE projects aiming at the modernization of the so called traditional evening and correspondence education. Training of experts and trainers, establishment of Regional Training Centres and their network based on higher education institutions, and setting up of a National Methodological Centre were the main results of this activity (Tóth, 2002). 6.4. Present situation At present, all higher educational institutions are connected through broadband fibre optic cable and broadband (ADSL) Internet access is provided to all (5500) primary and secondary schools. Until 2006 in the National Development Plan the Human Resource Operative Programme is responsible for building lifelong learning skills and pedagogical methodology reform in primary and secondary education using a competence-based approach (Horváth, 2004). Concerning teachers of all subject areas, the Ministry of Education initiated in-service teacher training and incentives for purchasing computing instruments: Till the spring of 2004, ICT training for 10 000 teachers; 2004-2006: ICT training for 30 000 teachers for competence based education combined with incentives for purchasing computing products through tax allowance policies (Magyar, 2004). 6.5. Sulinet Digital Knowledge Base & Portal The content development strategy of Hungarian SchoolNet (Sulinet) can be determined according to two target areas (Főző & Pap, 2004; Abonyi-Tóth, 2006): The Sulinet webpage – The goal is to operate a well functioning educational portal, which attends 50,000 visitors a day. Development of digital educational auxiliary materials, which are usable in the field of the public education as open source. The Sulinet Digital Knowledge Base (SDT Web site - http://sdt.sulinet.hu/), edited and managed by Sulinet, aims to establish a complete electronic database covering all the cultural domains of primary and secondary education specified in the Hungarian National Curriculum. The available database offers lesson plans, methodological support, subject matters and basic learning blocks for teachers and students to use in the everyday teaching/learning process. The use of SDT is free of charge for all individuals and educational institutions within Hungary and those beyond the borders. It aims to serve not only public education, but also ITE and CPD. The different elements of the Knowledge Base (pictures, texts, sound- and video files) are designed as re-usable LOs and are placed into a Learning Content Management System (LCMS) designed to suit local requirements. More than 200,000 reusable LOs are placed within the LCMS. Different users are entitled to go through different paths depending on their preferences, levels and purpose. Enhanced search facilities provide direct access to required 9 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers topics, and use of bookmarks ease the process of collecting entry points to revisit. Materials can be accessed thematically; through designed paths; searched titles, keywords, and other specified tags; established connections via an internal concept graph, which also serves as visualization tool for knowledge integration. The internal storage of data and the publishing complies with international standards (SCORM, IMS, LOM, Dublin Core) to attain re-use and portability of content. The structure of the system also makes it possible to publish the materials in other interfaces like mobile phones or palmtops. Functionality allows not just browsing and download of materials, but also editing new materials or adapting existing content to suit specific needs. The system is also equipped with messaging, forum, and activity area to facilitate project work and collaboration. Besides, Sulinet portal (Sulinet Web site - http://www.sulinet.hu/tart/kat/Re) publishes auxiliary educational materials and subject matter blocks too as well as methodological information. The portal consists of 4 sub-portals (e-Learning, School, Pedagogy, Systems administrator) with 28 sections altogether. School bodies can find all sorts of information they need and can easily exchange with others on topics and experiences. In addition Sulinet also launched a 30 hours ICT based modular in-service teacher training program consisting of ten modules that can be attended all over the country (Sulinet Express Web site http://www.oki.hu/printerFriendly.php?tipus=cikk&kod=link-Sulinet-Express). Thus, the Hungarian approach embedded within Sulinet provides a unique environment with equal access for all citizens and Hungarian nationals around the world, to be part of the learning community, allowing participants to take active role in further perfection of the established knowledge base as members of a community of practice in the educational arena of the 21st century. 6.6. Teacher Training at ELTE University Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE University Web site - http://www.elte.hu/en/) was the first to introduce computers into the teacher training programs. Students with several types of majors attended introductory computer and programming courses as well as their applications in subject areas. ELTE University is the biggest university in Hungary which, apart from other subject areas, produces the largest amount of teachers in the field of informatics and prepares all teachers for the use of ICT in education. Its educational policy, which was very highly programming oriented, has shifted more towards the use of ICT in subject areas rather than the heavy emphasis in the learning of the technology and computer science itself. EPICT – The European Pedagogical ICT Licence is a comprehensive, flexible and efficient in-service training course introducing a European quality standard for the continued professional development of teachers in the pedagogical integration of information, media and communication technologies (ICT) in education, controlled internationally by the EPICT Group (EPICT Group Web site - http://www.epict.eu/about_epict/index.html). The Hungarian representative is the Centre for Multimedia and Educational technology (MULTIPED Web site - http://edutech.elte.hu/kozpont/english/index.html) based at the Faculty of Sciences at ELTE University, serving teacher training faculties of the university with courses on Educational Technology and ICT in Education. 10 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers 6.7. Special projects at ELTE University The emphasis of Informatics is so high in the country, that three years ago the Faculty of Informatics was established within ELTE University, which considers – among others – the training of informatics experts and teachers, continuing their pioneer activities of integrating ICT into TE in a more effective setup. Besides the official courses in teacher training, there are special projects that help infusion of innovation within public education initiated within TE. An example is the practice of ELTE University TeaM lab (TeaM Lab Web site http://teamlabor.inf.elte.hu/), which offers courses for higher graders as undergraduate noncompulsory electives, mainly within the Informatics teacher training program and secondly for programmer and program designer mathematicians with relation to developing e-learning materials and running projects in public education (Turcsányi-Szabó, 2006a). All courses require project work that outlines a definitive part of an actual project to be launched and the sequence of courses contribute to the building, launching, running and evaluating processes within project activities. Projects are launched directly into public education often in association with the national computer society (John von Neumann Computer Society, Public Education SIG - http://njszt-kozokt.inf.elte.hu/) and results are reported twice a year at the conferences for Informatics Teachers (INFO conferences Web site - http://www.infoera.hu/), where discussions with practicing teachers can produce important conclusions for the future. One such project type is the TeaM Challenge Game series (TeaM Challenge Game series Web site - http://matchsz.inf.elte.hu/kihivas/), launched every year since 2002 (TurcsányiSzabó et al. 2006). TeaM lab initiates projects not only for formal public education, but also for tele-centres in underdeveloped regions as capacity building initiative, during which a model for mentoring has been developed (Turcsányi-Szabó, 2003), which is since then successfully utilised within the Hungarian tele-centre community (Telehouse association http://www.telehaz.hu/). Another such continuous project is the development of subject oriented microworlds for elementary education and special education. In fact, e-learning material for teachers has been developed in 1996 within NETLogo project on how to use, configure and design such microworlds using Comenius Logo as authoring tool (Turcsányi-Szabó, 2000). This material was later extended and adapted to suit elementary education as well and was used for many years at ELTE university ITE in blended courses and opened for the public (visited by both in-service teachers and students), mentored online by future teachers themselves (TurcsányiSzabó, 2004). At present, ITE uses the localised version of Imagine authoring tool and an elearning material developed by TeaM lab, which has been adapted as LOs for Sulinet SDT “Digital literacy” course (Turcsányi-Szabó, 2006b) and can be accessed freely by public education for use in class-work too. The English language version of this material is also available through Logotron Ltd. (Turcsányi-Szabó, 2006c) and is distributed in English language cultures. Thus, it can be said, that TeaM lab not only takes part intensively in face-to-face and online ITE, but also develops the necessary e-learning materials which are suitable for both training purposes and for direct use in class-work. Thus formal and informal CPD also profits through direct use of materials in schools and at homes for which online-mentoring is provided. 11 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers 7. CONCLUSION ITE and CPD varies in forms, resources, methods and delivery along the different countries in Europe and beyond, but case-studies suggest that ICT use is a benchmark for success and the effectiveness of all initiatives depend on the fluent use of enhanced technology, availability of adequate and suitable LOs, the setup of suitable virtual learning environments, and initiation of innovative projects that allow an integrated approach to pedagogy and technology as a virtual extension of formal and informal learning in general. Research on the actual effectiveness of these tools and resources is in an early stage and the concrete parameters of success and are yet to proven. However, it is well visible, that lessons are worth learning from other cultures and regions as there is always something new and innovative to examine, try out and if proven, to adapt to local needs. The overview of the picture is quite wide on an international scale and all countries should find their own profile, depending on capabilities to utilise the right tools and methodology that would really able them to make changes with the needed impact. It might well be different from country to country as the add-on values of local communities can be highlighted only if appropriate basic requirements are met on which a well designed structure of schooling is built on, that can be flexibly adopted according to needs. REFERENCES 1. Abonyi-Tóth, A. (2006). The Role of Education portals in Hungary – are Teachers Facing Change in Methodology? In (eds.) Dagiene, V., Mittermeir, R., Proceedings of ISSEP 2006, pp. 281-296. 2. Fisher, T. (2003). Teacher Professional Development through Curriculum Development: teachers’ experiences in the field training of online curriculum materials. In Technology, Pedagogy and Education, Vol 12, No 3. , pp. 329-343. 3. Főző, A., & Pap, É. (2004). Digital Knowledge Base Program, International workshop of IFIP WG 3.5 Book of Abstracts, pp117-118, Budapest, Hungary. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://matchsz.inf.elte.hu/ifip2004/program/A_Fozo_AS.doc 4. Glen, M., & Farrel, D. (2003). An Overview of Developments and Trends in the Application of Information and Communication Technologies in Education, UNESCO, Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ict/Metasurvey/2Regional04.pdf 5. (ed.) Haddad,W.D., & Draxler, A. (2002). Technologies for Education – Potentials, Parameters, and prospects. UNESCO, Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001191/119129e.pdf 6. Horváth, Á. (2004). State of eLearning in Hungary. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.gpi-online.de/upload/PDFs/ESEC_0405/Internetpublikation/B-_und_E_Learning/HU-Horvath-eLearningHA.pdf 7. Ilomaki, L., Lakkala, M., & Paavola, S. (2006). Case studies of learning objects used in school settings. In Learning, Media and Technology, Vol. 31, No 3. , pp. 249-267. 8. Kim, K., Isenhour, P.L., Carroll, J.M., Rosson, M.B., & Dunlap, D.R. (2003). TeacherBridge: Knowledge Management in Communities of Practice. In Proceedings of H.O.I.T. 2003, California, USA. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.crito.uci.edu/noah/HOIT/HOIT%20Papers/TeacherBridge.pdf 12 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers 9. (ed.) Kvaternik, R. (2002). Teacher Education Guidelines: Using Open and Distance Learning, Technology – Curriculum – Cost – Evaluation, UNESCO. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001253/125396e.pdf 10. Magyar, B. (2004). School of the Future, International workshop of IFIP WG 3.5 Book of Abstracts, pp117-118, Budapest, Hungary. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.om.hu/letolt/english/school_of_future.ppt 11. (ed.) Majumdar, S. (2005). Regional Guidelines on Teacher Development for PedagogyTechnology Integration (Working Draft). Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001405/140577e.pdf 12. McCormick, R., & Li, N. (2006). An evaluation of European learning objects in use. In Learning, Media and Technology, Vol. 31, No 3., pp. 213-231. 13. (ed.) Midoro, V. (2005). EUROPEAN TEACHERS' TOWARDS THE KNOWLEDGE SOCIETY , Menabo edizioni. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://ulearn.itd.ge.cnr.it/uteacher/docs/European.pdf 14. Nurmi, S., & Jaakkola, T. (2006a). Effectiveness of learning objects in various instructional settings. In Learning, Media and Technology, Vol. 31, No 3., pp. 233-247. 15. Nurmi, S., & Jaakkola, T. (2006b). Promises and itfals of learning objects. In Learning, Media and Technology, Vol. 31, No 3. , pp. 269-285. 16. Perraton, H., & Creed, C., Robinson, B., (2002) Teacher Education Guidelines: Using Open and Distance Learning, UNESCO, Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001253/125396e.pdf 17. (ed.) Resta, P. (2002). Information and Communication Technologies in Teacher Education: A Planning Guide. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001295/129533e.pdf (accessed 11 December 2006) 18. Richards, C. (2006). Towards an integrated framework for designing effective ICTsupported learning environments: the challenge to better link technology and pedagogy. In Technology, Pedagogy and Education,, Vol 15, No 2. , pp. 239-255. 19. Rodrigues, S. (2006). Pedagogic practice integrating primary science and elearning: the need for relevance, recognition, resources, reflection, readiness and risk. In Technology, Pedagogy and Education, , Vol 15, No 2. pp. 175-189. 20. Somekh, B., (2004). Taking the Sociological Imagination to School: an analysis of the (lack of) impact of information and communication technologies on education systems. In Technology, Pedagogy and Education, pp. 163-179, Vol 13, No 2. 21. Tóth, É. (2002). Teaching and the use of ICT in Hungary, International Labour Office, Geneva, Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www-ilomirror.cornell.edu/public/english/dialogue/sector/papers/education/wp199.pdf 22. Turcsányi-Szabó, M. (2000). Subject Oriented Microworld Extendable environment for learning and tailoring educational tools a scope for teacher training, Proceedings of 16th IFIP World Computer Congress, pp. 387-394, ICEUT 2000, Beijing, China. 23. Turcsányi-Szabó, M., & Ambruszter, G. (2001). The past, present, and future of computers in education the Hungarian image, International Journal of Continuing Engeneering Education and Life-Long learning, UNESCO, Volume 11, Nos 4/5/6., pp. 487-501. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from 13 Section 7: IT and Distance Learning in K-12 Education Chapter 6: Online Professional Development for Teachers https://www.inderscience.com/search/index.php?action=record&rec_id=413&prevQuery= &ps=10&m=or 24. Turcsányi-Szabó, M. (2003). Practical Teacher Training Through Implementation of Capacity Building Internet Projects, Proceedings of SITE 2003, abstract pp. 189, full paper on CD, Albuquerque, New Mexico USA. 25. ed. Turcsányi-Szabó, M., (2004). “HÁLogo portal” (Hungarian NETLogo portal with elearning material). Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://kihivas.inf.elte.hu/halogo, ELTE University TeaM Lab. 26. Turcsányi-Szabó, M. (2006a). Blending projects serving public education into teacher training. In Kumar, Deepak; Turner, Joe (Eds.) Education for the 21st Century – Impact of ICT and Digital Resources, IFIP 19th World Computer Congress, TC-3 Education, IFIP series Vol. 210, pp. 235-244, Springer. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.springerlink.com/content/k8q6107r3gu60838/ 27. ed. Turcsányi-Szabó, M. (2006b). “Elektronikus Írásbeliség” (Digital Literacy e-learning material), Sulinet Digitális Tudásbázis (Course material for Schoolnet Digital Repository), Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://sdt.sulinet.hu/. 28. Turcsányi-Szabó, M. (2006c). Creative Classroom CD Logotron Ltd, Cambridge, Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.logo.com/cat/view/creative_classroom.html. 29. Turcsányi-Szabó, M., Bedo, A., Pluhar, Zs. (2006). Case study of a TeaM Challenge game – e-PBL revisited, ed. Watson, D. Education and Information Technologies, No.4 October 2006. Springer. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.springerlink.com/content/t4896677504820u2/ 30. UNESCO – Teacher Education Web site (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://portal.unesco.org/education/en/ev.phpURL_ID=40218&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html 31. UNESCO Bangkok – ICT in Education Web site (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.unescobkk.org/index.php?id=76 32. UNESCO (2004a). A Collective Case Study of Six Asian Countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education, 2004, 9 vols. ISBN 92-9223-015-8 . Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.unescobkk.org/index.php?id=1793 33. UNESCO (2004b). SchoolNetworking: Lessons Learned Vol 2., A Collective Case Study of Five Asian Countries: Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand (ICT lessons learned series 2004, Vol. 2), UNESCO Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education, 2004, 9 vols. Retrieved April 28, 2007, from http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ict/ebooks/ICT_lessonslearned2/Scheelnetworking.pdf 34. Webb, M., & Cox, M. (2004). A Review of Pedagogy Related to Information and Communications Technology. In Technology, Pedagogy and Education, , Vol 13, No 3. pp. 235-286. 35. Wikipedia – Distance Education Web site (n.d.). Retrieved December 28, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Distance_education 36. @Teacher web site (n.d.). – National Reports Retrieved April 28, 2006, from http://ulearn.itd.ge.cnr.it/uteacher/national_reports.htm. 14