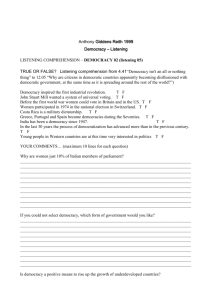

MEDIA ROUND TABLE REPORT

advertisement