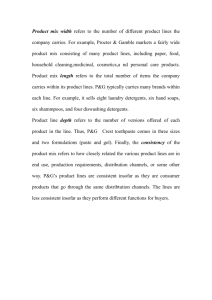

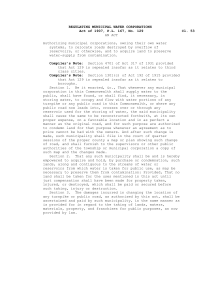

first part of the ethics

advertisement