近代日本における宗教と社会活動 My concern is to understand what

advertisement

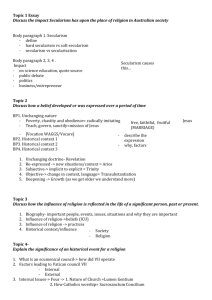

近代日本における宗教と社会活動 My concern is to understand what moved people to social action, in particular, in nineteenth century Japan and how this can be located within a broader comparative context. To address this question it is necessary to define the contours of the intellectual topography during this period and I would argue that the exclusion of ‘religion’ has obscured the contours of this topography. The exclusion of religion as a defining element obscures the motivations but also serves to strengthen the presence of the so-called ‘West’ as the defining element in shaping modern Japan. complex ways in which social movements arose. The modern state and its relationship with religious groups and their exclusion from public affairs is now being thought afresh. Amongst others Talal Asad has questioned the universal definition of religion and secularism and shown the varieties of secularism within the Western world.1 He has argued that ‘religion’, as it is generally defined, is a modern Western invention, and so underlined the need to rethink the religious-secular dichotomy. He argues that secularism is not just when human life emancipates itself from religion but indeed it is a political strategy to build a particular conception of the world. In the case of early modern Europe the project of secularism was used to control the mobile poor, govern hostile sects and regulate colonial expansion.2 I would like to take Talal Asad’s assertion as my starting point to think about the varieties of secularism and religion in the context of Japan. The long process through which modern rationality became the accepted idiom of political discourse produced the view that the Japanese are not a religious people, indeed religion was dismissed as largely irrelevant and became the preserve of religious specialists. Culture became the defining element This view was accepted despite a vast range of research that showed the pervasive influence of religious groups in forming the political and social landscape of modern Japan. The large followings of the established Buddhist sects as well as the growth of popular religions at different times was largely ignored in the general explanations of Japanese history. It is my contention that religion has been an integral part and shaped the political discourse in complex ways. I take two examples to look for an answer to the question of the shaping of the political discourse and the examining of secular. One the life of Kitabatake Doryu to ask the question why did a Honganji monk work to establish a people’s militia, study law and establish a law school and then go on to propagate gender quality. And two, Kimura Shigeki 木村卯之 who sought to define Japan’s identity in terms of culture and link this to a statist conception, that is the restoration of the state would lead to a strong culture. These two very different conceptions provide a way to understand the ways in which Japanese win the nineteenth and twentieth century were defining the secular world. Talal Asad, Genealogies of Religion:Discipline and Reasons of Power in Christianity and Islam, John Hopkins University Press, 1993. 2 Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam Modernity, Stanford 1 University Press, 2003, pp192.