Chapter 6: Benefits and costs of the DDA

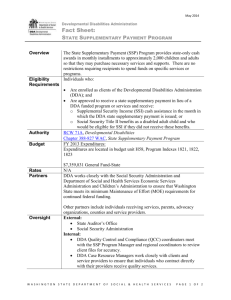

advertisement