Chapter 3: The Money Market and the Federal Reserve

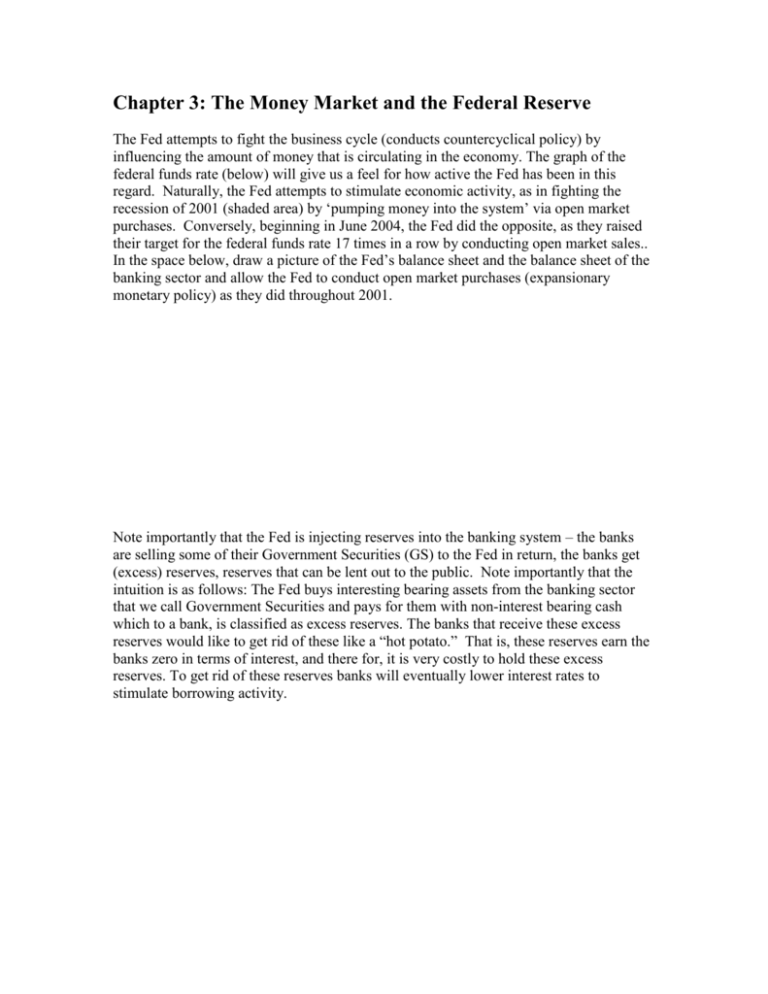

The Fed attempts to fight the business cycle (conducts countercyclical policy) by

influencing the amount of money that is circulating in the economy. The graph of the

federal funds rate (below) will give us a feel for how active the Fed has been in this

regard. Naturally, the Fed attempts to stimulate economic activity, as in fighting the

recession of 2001 (shaded area) by ‘pumping money into the system’ via open market

purchases. Conversely, beginning in June 2004, the Fed did the opposite, as they raised

their target for the federal funds rate 17 times in a row by conducting open market sales..

In the space below, draw a picture of the Fed’s balance sheet and the balance sheet of the

banking sector and allow the Fed to conduct open market purchases (expansionary

monetary policy) as they did throughout 2001.

Note importantly that the Fed is injecting reserves into the banking system – the banks

are selling some of their Government Securities (GS) to the Fed in return, the banks get

(excess) reserves, reserves that can be lent out to the public. Note importantly that the

intuition is as follows: The Fed buys interesting bearing assets from the banking sector

that we call Government Securities and pays for them with non-interest bearing cash

which to a bank, is classified as excess reserves. The banks that receive these excess

reserves would like to get rid of these like a “hot potato.” That is, these reserves earn the

banks zero in terms of interest, and there for, it is very costly to hold these excess

reserves. To get rid of these reserves banks will eventually lower interest rates to

stimulate borrowing activity.

8

Shaded Area = 2001 Recession: March - Nov (2001)

6

4

2

0

1/01/97

11/01/00

9/01/04

Federal Funds Rate

The Fed conducts open market operations every business day – they guess where reserve

demand is and supply the necessary reserves in hopes of hitting their Federal Funds Rates

target! Sometimes they are wrong. When the federal funds rate is high, then the Fed

underestimated reserve demand – that is, (actual) reserve demand was larger than they

thought it would be. Conversely, if the federal funds rate is lower than target, they

overestimated reserve demand. The Fed guesses what reserve demand will be every

business day, and conducts the appropriate amount of open market operations in hopes of

hitting the FF target as set by the FOMC.

In the space below using the information given, draw a reserve market diagram and

depict what the Fed does every business day in hopes ‘hitting’ the federal fund rate target.

Note that this is actual data from the fall of 2007 and the federal funds rate target is

4.75%.

Oct

8

4.77

Oct

9

4.91

Oct

10

4.52

Oct

11

4.75

Summary

The Fed tries to hit the target for the Federal Funds rate every business day by

conducting open market operations – the buying and selling of Government Securities on

the open market. This target is carefully chosen and is set in accordance with the Fed’s

ultimate objectives of full employment, economic growth, and price stability.

The Discount Rate and Discount Rate Policy

A relatively recent and definitely a major change in the Fed’s discount rate policy:

The articles explain what the discount window is and how the policy regarding the

discount window has changed. Be sure to understand exactly what the change implies for

the upper (intra-day) limit of the federal funds rate.

May 17, 2002

ECONOMY

Fed Proposes a Big Change

In Its Emergency Lending

By GREG IP

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

WASHINGTON -- The Federal Reserve, trying to make its management of interest rates more

effective, is overhauling the way it makes loans to commercial banks through its discount

window.

The changes won't affect the stance of monetary policy. Under the proposed changes, the

discount rate would be significantly higher than it is now but discount window credit would be

granted with far less stringent conditions. This is meant to reduce the stigma and administrative

burden of using the discount window, thus increasing its use.

The discount window used to be an important supplement to open-market operations: It was a

way for the Fed to supply cash to banks and thus maintain its control over interest rates. But it

has fallen into disuse, as banks have become better at managing their cash needs. Furthermore,

because the Fed requires a bank to exhaust alternative sources of funds before granting the bank

discount window credit, banks avoid the discount window for fear of suggesting to the market

that they are in distress.

When the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks disrupted banks' access to the money markets, the Fed

publicly announced the discount window was available in part to remove that stigma. That

week, discount window loans topped $45 billion, a record. They typically fluctuate between $25

million and $300 million.

"There is an alleged stigma to the discount window and we intend to get rid of that," said Fed

Governor Edward Gramlich.

By boosting use of direct loans to commercial banks, Fed

officials hope they will prevent volatility in the important

federal-funds rate due to temporary shortages of funds. The

federal funds rate is the rate commercial banks charge on

overnight loans to each other. Fed officials also hope to head

off any loss of control over interest rates resulting from

ongoing changes in the bank industry.

The discount rate is now 1.25%, a half-percentage point

beneath the 1.75% federal-funds rate target. Under the

proposal, on which the Fed is seeking comment, the discount

rate would be initially set a full percentage point above the

funds rate target, but that spread could then vary. The Fed

would be able to cut the discount rate quickly in an

emergency.

Furthermore, "primary" discount window credit would be granted to sound banks with few

questions asked and without requiring a bank to first exhaust alternatives. By setting the

discount rate above the funds rate, banks will be discouraged from using it as a routine funding

source. Troubled banks will be eligible for more restrictive "secondary" credit at a discount rate

charged half a percentage point above the primary discount rate.

But when the funds rate spikes above the Fed's intended target, banks are expected to turn to the

discount window -- relieving the pressure on market rates. Such spikes were common in the

early 1990s as hard-pressed banks sought ready cash but avoided the discount window. Today

spikes are more often the result of temporary funding pressures, such as when banks are

dressing up their balance sheets at quarter-end.

But the Fed also wants to prevent interest-rate volatility from rising because of changes in the

bank industry. Banks are required to hold a portion of their deposits on reserve at the Fed, and

the central bank manages interest rates by increasing or decreasing such reserves through open

market operations. In recent years, required reserves have been dropping as money-market

"sweep" accounts, which have no reserve requirements, spread. That trend could eventually

make it harder for the Fed to target interest rates precisely. The new discount-window system

could prevent that from happening.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com2

Updated May 17, 2002 8:53 p.m. EDT

Copyright 2002 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Printing, distribution, and use of this material is governed by your Subscription

agreement and Copyright laws.

For information about subscribing go to http://www.wsj.com

From Url: http://www.frbsf.org/education/activities/drecon/2004/0409.html

Ask Dr. Econ

I find definitions of the federal funds rate stating that it can be both

above and below the discount rate. Which is correct? (September 2004)

Great question! The correct answer depends on the time period. Since January

2003, when the Federal Reserve System implemented a “penalty” discount rate

policy, the discount rate has been about 1 percentage point, or 100 basis points,

above the effective (market) federal funds rate. The fed funds rate is the interest

rate that depository institutions—banks, savings and loans, and credit unions—

charge each other for overnight loans. The discount rate is the interest rate that

Federal Reserve Banks charge when they make collateralized loans—usually

overnight—to depository institutions.

The federal funds market

The fed funds rate and the discount rate are two of the tools the Federal Reserve

uses to set U.S. monetary policy. Let’s start by describing the more important of

these two short-term interest rates—the fed funds rate.

First, you should know that depository institutions are required by the Federal

Reserve to keep a certain amount of their deposits as required reserves, in the

form of vault cash or as electronic funds in reserve accounts with the Fed.1 Over

the course of each day, as banks pay out and receive funds, they may end up

with more (or fewer) funds than they need to meet their reserve requirement

target. Banks with excess funds typically lend them overnight to other banks that

are short on funds, rather than leaving those funds in their non-interest bearing

reserve accounts at the Fed or as idle vault cash.

This interbank market is known as the federal funds market and the effective

interest rate on daily transactions in this market is known as the federal funds

rate. As of September 2004, U.S. commercial banks reported about $360 billion

in daily average interbank loans, mostly federal funds loans—so you can see this

is a very important market for banks to make short-term adjustments to their

funding.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco publication, U.S. Monetary Policy:

An Introduction describes how the fed funds market works:

The interest rate on the overnight borrowing of reserves is called the federal

funds rate or simply the "funds rate." It adjusts to balance the supply of and

demand for reserves. For example, if the supply of reserves in the fed funds

market is greater than the demand, then the funds rate falls, and if the supply of

reserves is less than the demand, the funds rate rises.

Monetary policy and the fed funds rate

For monetary policy purposes, the Federal Reserve sets a target for the federal

funds rate and maintains that target interest rate by buying and selling U.S.

Treasury securities. When the Fed buys securities, bank reserves rise, and the

fed funds rate tends to fall. When the Fed sells securities, bank reserves fall, and

the fed funds rate tends to rise. Buying and selling securities, or open market

operations, is the Fed’s primary tool for implementing monetary policy.

Borrowing from the Fed’s Discount Window

Additionally, banks may borrow funds directly from the discount window at their

District Federal Reserve Bank to meet their reserve requirements. The discount

rate is the interest rate that banks pay on this type of collateralized loan. On a

daily average basis in September 2004, borrowing at the discount window

averaged only $335 million a day, a tiny fraction of the $360 billion daily

average for interbank loans during that month.

The following quote from the U.S. Monetary Policy: An Introduction, describes

how the discount window works and the discount rate is set:

The Boards of Directors of the Reserve Banks set these rates, subject to the

review and determination of the Federal Reserve Board… Since January 2003,

the discount rate has been set 100 basis points above the funds rate target,

though the difference between the two rates could vary in principle. Setting the

discount rate higher than the funds rate is designed to keep banks from turning to

this source before they have exhausted other less expensive alternatives. At the

same time, the (relatively) easy availability of reserves at this rate effectively

places a ceiling on the funds rate.

Historical comparison: Which rate was higher?

Historically the federal funds rate has been both above and below the discount

rate, although until 2003 the funds rate typically was above the discount rate.

Until January 2003, it was possible for the effective fed funds rate to fall below

the discount rate on occasion; however, normally the funds rate exceeded the

discount rate. This relationship can be seen in the Chart 1, which plots both the

interest rates and the difference between the two rates. The effective fed funds

rate (in black) and the discount rate (in yellow before 2003 and red after 2002)

compare the level of interest rates—note that since the January 2003 change in

discount window policy the discount rate has exceeded the fed funds rate.

The line centered on zero in the chart is the difference between the two interest

rates; it is calculated as the fed funds rate less the discount rate. Before 2003,

the line showing the difference between the two interest rates (shown in orange)

indicates that the funds rate typically was above the discount rate by a small

margin. However, since the change to a “penalty” discount rate policy in January

2003, the funds rate (shown in pink) has been consistently below the discount

rate.

Chart 1

Endnotes

1A bank’s reserve requirement is determined by a percentage the amount of deposits a

bank has, so each bank’s reserve requirement is different. For current reserve

requirements, please see Reserve Requirements of Depository Institutions at:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reservereq.htm.

References

Instruments of the Money Market. (1998) Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

http://www.rich.frb.org/pubs/instruments/

Selected Interest Rates (H.15 Release). Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve

System. http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/

U.S. Monetary Policy: An Introduction. (2004) Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

http://www.frbsf.org/publications/federalreserve/monetary/index.html

In the space below, draw a reserve market diagram and depict how the relatively new

discount rate policy effectively puts and upper bound on the federal funds rate.

Connecting the market for overnight reserves to the

money market

Our objective is to understand both sides of the money market – money supply where the

Fed plays a major role and money demand.

We begin with a world with two assets – money and bonds. More generally, we

want to define money as a non-interest bearing asset that is used for transaction purposes

(transactions money). Bonds on the other hand are less liquid, interest bearing, and

cannot be used directly for transactional purposes. Jumping forward, these points are

important in determining money demand – for example, if interest rates are very high,

then you will hold more bonds since it is so ‘costly’ to hold money. Naturally, low

interest rates mean that the costs of holding money are low so you tend to hold more

money . These are important issues in terms of money demand – but we will do money

supply first.

Money Supply

When we think of money supply, we think of the Fed: Doesn’t the Fed control

the money supply?? Sort of – let’s be precise and say that the Fed has a lot of influence

over the money supply – in particular, M1, which is the monetary aggregate that includes

the most liquid assets: Cash (Currency) and Demand Deposits (Checking accounts). M1

also includes travelers’ checks. There other major monetary aggregate is M2 which is a

broader measure of money that includes all of M1 plus some small time savings deposits

(i.e., M2 includes assets that are less liquid than M1). The Fed used to measure and

monitor M3 which was even broader than M2, but discontinued it measurement in

March, 2006, arguing that the costs of collecting the data exceeds the benefits of

collecting the data.1

The purpose of the few equations below is for you to understand that the Fed has

imperfect control of the money supply due to changes in household and bank behavior

that influences the money multiplier and in turn, influences the money supply. We will

use the great depression as an example to drive home this point. We will also mention

Y2K in this context.

Money Supply

Define money as above:

1) M = C + D where C = currency (cash) and D = demand deposits (checking accounts)

The Fed has pretty darn good control over what is referred to as the monetary base (MB)

(also referred to as high powered money since changes in MB due to open market

operations result in high powered effects, via the money multiplier, on the money

supply). Define MB as follows with C = currency as before, TR equals total reserves, a

combination of required reserves (RR) and excess reserves (ER).

2) MB = C + TR

Divide 1) by 2)

3) M/MB = (C + D)/(C + TR)

Now a “trick” – divide the numerator and denominator of the RHS (right hand side) of 3)

by D

4) M/MB = (C /D+ D/D)/(C/D + TR/D)

Let’s do a few things to 4) – a) get MB on RHS, b) D/D = 1, and c) TR = RR + ER

5) M = [(C /D+ 1)/(C/D + RR/D + ER/D)] MB

The term in brackets is referred to as the money multiplier, which is a little

different than what you saw in principles. Equation 5) implies that the money multiplier

is influenced by household behavior via C/D, which is determined by us. C/D is simply

the currency to deposit ratio. For example, if you typically carry $100 in cash and you

have $1000 in a demand deposit, then your C/D is 0.1. Think about what happened to

C/D during Y2K.

A quote from the website of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors: “ M3 does not appear to convey

any additional information about economic activity that is not already embodied in M2 and has not played a

role in the monetary policy process for many years. Consequently, the Board judged that the costs of

collecting the underlying data and publishing M3 outweigh the benefits.”

1

Equation 5) also implies that bank behavior influences the money multiplier via

ER/D. Even though banks tend to get rid of excess reserves (ER) since they earn zero

interest, sometimes they hold on to them. What do you think banks were doing during

Y2K? Probably holding a lot of ER to meet the liquidity needs of their customers (they

anticipated significant withdrawals)!

The last player that has influence over the money multiplier is the Fed themselves

via RR/D which is simply the reserve requirement ratio (this is what you were supposed

to learn in principles). Note that if we let C/D and ER/D equal zero, the money multiplier

collapses to 1/(RR/D) which is the ‘simple’ money multiplier that you may or may not

have learned about in principles.

Specifics on the money multiplier: If C/D, ER/D, or RR/D go up, then the

multiplier falls. This is important, because if MB remains constant, the money supply

will fall along with the multiplier. We will now use an example that is a simplified

version of what happened during the great depression.

Graphical Analysis, connecting the reserve market to the money market.

Initial Conditions

Let C/D = .2 , RR/D = .1 and ER/D = 0

Money Multiplier = (.2 +1)/ (.2 + .1 + 0) = 4

What does this mean?

A couple things: first, suppose the MB is $ 100 billion ; M = $ 400 billion

Second, a 10 billion dollar open market purchase will result in a $40 billion increase in

the money supply (remember high powered money!) See the two graphs below.

MB

MB’

i

i

100

110

Ms

Ms’

400

440

MB

M

The Great Depression – an Example

The Fed is blamed by some for causing the great depression or at the very least, failing to

respond appropriately as in they should of conducted more open market purchases! Of

course hindsight is 20/20.

What will a bank run do to C/D ratios?

So C/D rose dramatically as people were trying to get their cash – remember, there was

no FDIC insurance back then.

ER/D also rose for two reasons – one, banks were keeping ER to meet the liquidity needs

of their customers and two, had no one to lend to – banks are reluctant to make loans in

such a dismal environment (i.e., the default risk of the borrower is naturally high in such

a dismal environment).

Ironically, RR/D went up as well. The Fed was young, less than 20 years in existence

and felt that raising the required reserve ratio would make banks more sound as well as

giving the public more confidence so that they would not run on banks – in hindsight,

raising the required reserve ratio was a mistake!

All three components of money multiplier rose during the great depression – impact on

money multiplier?

Recall Money Multiplier equals:

[(C /D+ 1)/(C/D + RR/D + ER/D)]

Initially, let C/D = .2 , RR/D = .1 , and ER/D = 0

With numbers:

[(.2+ 1)/(.2 + .1 + 0)] = 4

Now account for changes in C/D, RR/D, ER/D

Let C/D up to .5, RR/D up to .2, ER/D up to .3

[(.5+ 1)/(.5 + .2 + .3] = 1.5

NEW Multiplier = 1.5

With numbers – before the great depression

M = ( 4 ) MB

If MB = $ 100 billion ; M = $ 400 billion

Now great depression hits and the multiplier falls to 1.5

MB still at $100 billion – M = 150 billion

Now the Fed isn’t blind – they buy $ 100 billion in Gov Securities, increasing MB by

$100 billion – Money Supply up to $300 billion (1.5 times $200 billion) – still a 25%

drop from where it was initially.

So the Fed pumped up the Monetary Base via open market purchases – but it was not

enough to offset the dramatic fall in the money multiplier – they should have been

easier!!

The lesson here is that the Fed has incomplete control over the money supply and in order

to have better control, they better try to figure out what determines C/D and ER/D ratios.

In normal times, these are pretty stable so that ‘normally,’ the Fed has pretty good control

over the money supply (M1).

In terms of graphs – in the reserve market, reserve supply doubled to $200 billion but in

the money market, Ms shifted to the left!

A few comments:

We have FDIC insurance now so bank runs are unlikely. The closest thing to a bank run

was the environment during Y2K. People didn’t trust computers and grabbed cash

instead. This was foreseeable, so the Fed, to offset the fall in the multiplier, should buy

lots of bonds thereby injecting lots of reserves into the system. Did they? Not exactly –

they used the discount window instead. They essentially told banks that you could

borrow all you need from us, the Fed, without worrying about the standard implicit cost

from borrowing from the Fed. Normally, banks are unwilling to borrow from the Fed

since borrowing from the Fed sends up a ‘red flag’ and increases the probability of being

audited by the Fed, something a bank certainly avoids. As a result, banks normally

would rather borrow off of other banks via the federal funds market. But during Y2k

they accepted the Feds offer and Y2k came and wend without incident.

Money Demand

The other half of the money market - money demand

There are two main determinants of money demand

First – real income – if your real income goes up you will live a better life and in order to

live a better life you consume more and in order to consume more you need to hold more

money. Graphically, an increase in real income (economic growth) shifts the money

demand curve to the right.

Second – the (opportunity) cost of holding money is the interest foregone by holding the

non-interest bearing money. The higher the interest rate, the higher the cost of holding

money so the less money you will hold. This idea gives us a negatively sloped money

demand as shown below.

i

6

A

B

4

Md (Y,PS)

400

440

M

For example, when rates are 6 percent, people hold 400 in money balances – quite costly

to hold money. An extreme case may help bring the point home – suppose for a second

that rates are 100% - how much money would you hold, a meals worth? Now suppose

rates are zero, how much money would you hold? Get the idea?

The variables in parentheses are shift variables – as noted before, a higher real income

means more transactions and more transactions require people to hold more money. The

PS term is included and stands for portfolio shocks – think again about Y2K. People

wanted to hold more money not because of lower interest rates or a change in real income

– they just wanted to readjust their portfolios due to Y2K. This would be depicted as a

rightward shift in money demand.

Note: In reality, it is next to impossible to clearly distinguish between real shocks to

money demand where money demand shifts due to changes in the real economy and

nominal or portfolio shocks to money demand where economic agents alter the

composition of the assets. From a monetary policy perspective, this distinction is critical.

PRACTICE PROBLEMS

An ‘old’ Homework Assignment

PLEASE BE AS NEAT AS POSSIBLE

Pretend you are in charge of conducting monetary policy.

Initial Conditions

rr/D= .10

C = 400 b

D = 1200 b

ER = 10

M=C+D

1)

a) Calculate the MB.

b) Calculate the money multiplier.

c) What is the money supply (use MS = m x MB)?

Please show all work

2) If Rd = 300 – 40 iff, given the information above, what is the market clearing federal

funds rate?

Draw a reserve market diagram depicting exactly what is going on here! Label the

equilibrium point as point A.

3) Suppose that the ff rate that clears the market in 2) above happens to be the federal

funds target that policy makers are happy with (i.e., they feel it’s in line with hitting their

ultimate objectives). If you were in charge of the operational aspect of the desk, that is, if

you were in charge of “hitting” the fed funds target, what must you do on a daily basis?

Be very specific!

4) Suppose that due to whatever reason, reserve demand changes and you forecast the

reserve demand to now be Rd = 250 – 40 iff

a) In order to keep the fed funds at target, what must the open market desk do? Be

specific and show this development in your picture above (label the new equilibrium as

point B).

b) Suppose the alternative, that the open market desk does nothing different, that is, they

hold the amount of reserves constant (the fed holds the money stock). What happens in

the reserve market? What is the market clearing fed funds rate now? Label this

development, that is, the new equilibrium as point C.

5) Let’s move on to the money market now.

a) Suppose the money demand function is given by:

Md = 2211 – 100i

What is the market clearing interest rate in the money market?

Show all work

b) Draw a money market diagram and label this initial equilibrium as point A.

Consistent with the shock to reserve demand, money demand also decreases. The “new”

money demand curve is now:

Md = 2011 – 100i

c) If the desk acts as they did in part 4) a), to keep the fed funds rate at target, what

would be the new market clearing interest in the money market? Show these

developments on your money market diagram and label this equilibrium as point B.

d) Now suppose the desk “Holds the money Stock,” what would be the market clearing

interest rate now? Label this equilibrium as point C.

e) Since you are the captain of the ship, how would you make your decision on whether

or not to conduct any open market operations? That is, tell me a nice detailed story as to

what goes into making this decision. There is a lot to discuss!

ANOTHER PROBLEM

Initial Conditions

rr/D= .05

C = 200 b

D = 800 b

ER = 10

M=C+D

a) (3 points)

a) Calculate the MB.

b) Calculate the money multiplier.

c) What is the money supply (use mm x MB to calculate this)?

Show work

b) (3 points) If Rd = 290 – 60 iff, given the information above, what is the market

clearing federal funds rate?

Show work

(4 points for correct diagram) Draw a reserve market diagram depicting exactly what is

going on here! Label the equilibrium point as point A.

c) (2 points) Suppose that the ff rate that clears the market in 2) above happens to be the

federal funds target that policy makers are happy with (i.e., they feel it’s in line with

hitting their ultimate objectives). If you were in charge of the operational aspect of the

desk, that is, if you were in charge of “hitting” the fed funds target, what must you do on

a daily basis? Be very specific!

d) Suppose that due to whatever reason, you forecast the reserve demand to be:

Rd = 300 – 60 iff

e) (2 points) In order to keep the fed funds at target, what must the open market desk do?

Be specific and show this development in your picture above (label the new equilibrium

as point B). In fed language, this is referred to as accommodating the shock to reserve

demand.

Show work

f) (2 points) Suppose the alternative, that the open market desk does nothing different,

that is they hold the amount of reserves constant (“the fed holds the money stock”). What

happens in the reserve market? What is the market clearing fed funds rate now? Label

this development, that is, the new equilibrium as point C.

Show work

Let’s move on to the money market now.

Suppose the money demand function is given by :

Md = 1500 – 100i

g) (2 points) What is the market clearing interest rate in the money market?

Show all work

h) (4 points for correct diagram) Draw a money market diagram (use space below) and

label this initial equilibrium as point A.

Consistent with the shock to reserve demand, money demand also increases. The “new”

money demand curve is now:

Md = 1600 – 100i

i) ( 2 points) If the desk acts as they did in part e), to keep the fed funds rate at target,

what would be the new market clearing interest in the money market. Show these

developments on your money market diagram and label this equilibrium as point B.

Show work:

j) (2 points) Now suppose the desk “Holds the money Stock,” what would be the market

clearing interest rate now? Label this equilibrium as point C.