Experience of black and minority ethnic staff in HE in England

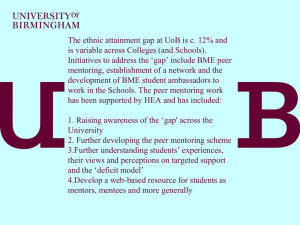

advertisement