The career of W.E.B. Du Bois, both as a philosopher and as an

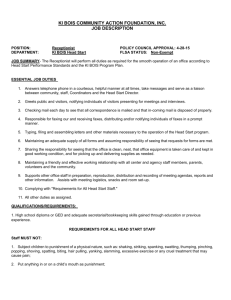

advertisement

The career of W.E.B. Du Bois, both as a philosopher and as an activist, has been marked, progressively, with two struggles. First, he engages in a life long struggle for a distinctive racial equality, which would both equalize races socially, politically, and economically, but without destroying the cultural essence of the different races by making them all conform to the same standards. Second, throughout his life Du Bois becomes increasingly involved in a struggle for economic justice, specifically funneled through a demand for socialism, and later, full communism. Each one of these struggles is formed through a moral emphasis on freedom, equality, and justice, the realization of which, to Du Bois, involves first and foremost a conception of freedom informed by positive rights, and socioeconomic equality. Both the positive rights Du Bois interprets as necessary for equal freedom between the different races, and the move from capitalism to a more equalized socialism, and later, communism, face serious obstacles if the libertarian critique of positive rights and absolute emphasis on property rights is upheld. In this essay, I will try to both articulate and defend Du Bois’ projects for racial and socioeconomic equality through arguing that they depend upon a notion of positive rights, and defending the desirability of positive rights against the libertarian critique of such a concept. More specifically, I will do this by first arguing that the distinction between negative and positive rights is unsound because of a collapse in the moral relevance of the distinction between actions and omissions. Second, I will apply the new structure of rights to reaffirm positive interpretations of basic rights, and pave the way for Du Boisian social and economic rights included in his definition of freedom. Third, I will show in retrospect why negative interpretations of rights were inadequate for remedying past systematic inequalities, such as racism. Finally, I will generalize the observation in (3) to show why private ownership of capital, contrary to the libertarian argument, necessarily violates rights. This process should solidify and support the Du Boisian project for equality. Throughout Du Bois’ career, he had been concerned to gain equality for African Americans. He increasingly began to see the struggle for racial equality to be connected with the struggle for economic equality and an abolition of the capitalist economic system. His earlier emphasis that each race has a distinct gift to deposit in the world funneled itself into a specific calling for his people to pave the way for change. In his essay, “My Evolving Program for Negro Freedom,” Du Bois articulates a belief that “13 millions of people . . . could so concentrate their thought and action on the abolition of their poverty, as to work in conjunction with the most intelligent body of American thought; and that in the future as in the past, out of the mass of American Negroes would arise a far-seeing leadership in lines of economic reform” (611). In particular, he demanded that rights be taken from theory to practice, and correspondingly from mere negative rights to substantially realized positive rights, or in his words, “in a program of mere agitation for “rights,” without clear conception of constructive effort to achieve those rights, I was not interested, because I saw its fatal weakness” (611). Later in that same piece, Du Bois laid the summation of the whole of his career in the struggle for civil rights. Du Bois demanded equal freedom, meaning “full economic, political, and social equality with American citizens, in thought, expression, and action, with no discrimination based on race or color” (613-14). Du Bois’ definition of freedom presupposes the political rights to vote and work for a decent wage (614), and he moves on to more specifically define the demand for social equality. The activities he refers to as social are: A. Private social intercourse (marriages, friendships, home entertainment). B. Public services (residence areas, travel, recreation and information, hotels and restaurants). C. Social uplift (education, religion, science and art). (614) Equality among the first category “means the right to select one’s own mates and close companions . . . an unquestionable right so long as my free choice does not deny equal freedom on the part of others” (614). Concerning the second category, “one’s right to exercise personal taste and discrimination is limited not only by the free choice of others, but by the fact that the whole social body is joint owner and purveyor of many of the faculties and rights offered” (614), and so “social equality . . . denies the right of any discrimination and segregation which compels citizens to lose their rights of enjoyment and accommodation in the common wealth” (615). Finally, in the third category, Du Bois chides private, discriminatory groups who claim to be or provide public institutions and services. He argues that the real freedom is “the right to be different, to be individual and pursue personal aims and ideals” (617). So far, his political and social freedoms (excepting perhaps some interpretations of the social category of public services) seem overtly to include only negative rights, i.e. a lack of coercively defined obstacles to freedom of choice, association, etc., for which libertarians would have little objection. These goals, and specifically the right to be oneself (or in Du Bois’ terms, to be individual), are the end goal of civilization, the securing of “the richness of a culture that lies in differentiation” (617). Before this end can be secured, however, Du Bois argues that a democracy must first provide “food, shelter and organized security for man” (617), in short, a positive right to sustenance. The summum bonum of a society of individual development can only be met “once the problem of subsistence is met and order is secured” (617), i.e. once both positive and negative interpretations of basic rights (sustenance and security, respectively) are fulfilled. Positive equalization of the lowly must occur for a world of individual development, as “world-wide equality of human development is the answer to every meticulous taste and each rare personality” (617). Seven years later, in his essay “There Must Come a Vast Social Change in the United States,” Du Bois argues even further that the most reasonable and just distributive principle is “to each according to his need and from each what he best can do,” (621) which is, in his eyes, “the high ideal” (621). More specifically, in his “Application for Membership in the Communist Party of the United States of America,” he approvingly lists the path of the American Communist Party: 1. Public ownership of natural resources and of all capital. 2. Public control of transportation and communications. 3. Abolition of poverty and limitation of personal income. 4. No exploitation of labor. 5. Social medicine, with hospitalization and care of the old. 6. Free education for all. 7. Training for jobs and jobs for all. 8. Discipline for growth and reform. 9. Freedom under law. 10. No dogmatic religion. (633) He argues that “capitalism cannot reform itself; it is doomed to self-destruction [because] no universal selfishness can bring good to all” (632), and that the American Communist Party platform he recommends should be pursued, for “no nation can call itself free which does not allow its citizens to work for these ends” (633). The libertarian position, here supported by Robert Nozick, contains severe criticisms of the notion of positive rights, upon whose realization Du Bois’ projects rely. Nozick begins his seminal libertarian treatise, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, with the statement “individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights)” (Nozick, ix). Rights are the most important consideration of justice, the paramount feature of the just state. To Nozick, rights are first and foremost not components of some end-state theory to maximized, for that would make one’s theory some sort of “utilitarianism of rights” (Nozick 28), whereby “this still would require us to violate someone’s rights when doing so minimizes the total (weighted) amount of the violation of rights in the society” (Nozick 28). Rights in this interpretation, instead of being absolute and inviolable, would be contingent and insecure. Nozick proposes that “in contrast to incorporating rights into the end state to be achieved, one might place them as side constraints upon the actions to be done: don’t violate constraints C” (Nozick 29). The root idea of the conception of rights as side constraints is that “there are different individuals with separate lives and so no one may be sacrificed for others” (Nozick 33), and that side constraints “express the inviolability of [these] other persons” (Nozick, 32). What rights, then, do people have under these side constraints? Nozick assumes the Lockean set of life, liberty, and property, and his conception of rights as side constraints, in conjunction with his arguments against end-state interpretations of rights and justice, compose his argument against positive interpretations of rights. To fulfill a positive interpretation of rights (especially with a positive interpretation of the right to life), and/or another patterned principle of distributive justice, to Nozick, would violate rights. Maintaining the taxation necessary to uphold such positive social provision would violate the absolute negative rights to liberty and property that Nozick upholds. He contrasts historical principles of distribution, whereby the justness of a distribution depends solely upon the justness of the transactions that resulted in that distribution, against end-state (e.g. patterned) principles, whereby the justness of a distribution depends upon “who ends up with what,” (Nozick 154) and not necessarily upon how that distribution arose1. 1 It should be noted, although irrelevant to the considerations thus far, that Nozick admits the possibility of there being a mix between historical and end-state principles, e.g. an end-state principle of distributive justice with side Nozick says that any patterned principle of justice would violate his absolute negative right to liberty, as “no end-state principle or distributional patterned principle of justice can be continuously realized without continuous interference with people’s lives” (163). This is because “to maintain a pattern one must either continually interfere to stop people from transferring resources as they wish to, or continually (or periodically) interfere to take from some persons resources that others for some reason chose to transfer to them” (163). Additionally, any patterned end-state principle would require some redistributive mechanism, which would violate individuals’ absolute negative property rights. Nozick says “the central core of the notion of a property right in X, relative to which other parts of the notion are to be explained, is the right to determine what shall be done with X” (Nozick 171). Taxation, which is involuntarily mandated by a state and coercively protected, would require people to give resources for the benefit of others that violate others’ free choice in doing what they want with what they have (according to a principle of just holdings). Finally, any holdings are just insofar as they are consistent with the first two principles of Nozick’s historical Entitlement Theory of justice. These principles are: (1) A person who acquires a holding in accordance with the principle of justice in acquisition is entitled to that holding. (2) A person who acquires a holding in accordance with the principle of justice in transfer, from someone else entitled to the holding, is entitled to the holding. (3) No one is entitled to a holding except by (repeated) applications of 1 and 2 (Nozick 151). Finally, the principle of justice in acquisition is that of Nozick’s interpretation of the Lockean proviso, interpreting Locke’s demand that, in initial acquisition, “enough and as good [should be] left in common for others” (qtd in Nozick 175) as being satisfied if others are no worse off than constraints on how transactions occur historically. He notes that an individual can maintain and end-state principle of morality or distributive justice that “may place the nonviolation of rights as a constraint upon action, rather than (or in addition to) building it into the state to be realized,” (Nozick 30) e.g. an end-state principle with side constraints attached, which would pass through his critique. they would be had the appropriated resource remained unappropriated (find quote). In short, (1) rights are completely and inalienably negative, (2) positive conceptions of rights require statecoerced actions that violate negative rights, and so (3) there are no positive rights, and (4) state provision of any services other than basic protective services is unjust (unless the funds come exclusively from voluntary donations and extend only to those who desire them). Consequentially, (5) any end-state social aim (such as equality in anything other than ‘basic negative rights’) violates rights, and is absolutely wrong and unjust. These positions, if upheld, would prove an obstacle to Du Bois’ projects. While under Nozick’s entitlement principles a strong case could be made that Native Americans would have most of the land of this country returned to them2, the applications of Nozick’s principles even then would not guarantee equal development, an end Du Bois prizes, and would eliminate the prospect of a socialist or communist society excepting a society with a majority absence of selfishness. Nozick’s case here hinges completely on (1) the distinction between negative and positive rights, and (2) the absolute inviolability of the former, and nonexistence of the latter, in addition to presuming (3) full capitalist property rights. To respond to the libertarian challenge, then, we need to collapse the distinction between negative and positive rights. Is the distinction legitimate? The distinction between positive and negative rights hinges upon the distinction between action and omissions. It is said that negative rights require for their satisfaction refraining from actions, whereas positive rights require positive action for their satisfaction. Thus, the traditional 2 In that this country was built on slave, i.e. stolen, African American labor, on top of stolen Native American land, land would be returned to the respective victimized tribes. What, however, would happen to the African Americans? distinction between negative and positive rights rests ultimately between the distinction between omissions and actions—but before we accept this traditional doctrine, we must first look at both kinds of rights, and see if negative and positive rights do consist of negative and positive duties, respectively. Henry Shue remarks that “rights cannot be understood without understanding what it means to fulfill them” (71), and in fact, every right corresponds to three sets of duties, some positive and some negative. These are: I. II. III. Duties to forbear from depriving right-holders of the substance of their rights. Duties to protect right-holders against the deprivation of the substance of their rights. Duties to aid right-holders in obtaining or regaining the substance of rights of which they are deprived. (Shue 76) The first of these duties are mostly negative, while the third are mostly positive (barring, of course, some unforeseen counterexample). The second duties contain elements of both kinds. Being that rights of all kinds have both positive and negative dimensions, it seems as though rights themselves are neutral, and the question becomes, then, whether positive duties are as valid as negative duties. Consequently, the distinction between action and omission is relevant to the discussion of rights, but insofar as it pertains to duties, instead of the traditional application where it pertains to the rights themselves. What distinguishes actions from omissions is the distinction between positive and negative instrumentality. Jonathan Bennett defines someone as “instrumental in the obtaining of a state of affairs S if S does indeed obtain, and if the person’s conduct makes the difference if . . . it hoists S’s probability up from 0 or hoists it up to 1” (Bennett 61). One is positively instrumental if one’s action makes S more likely to obtain, and negatively instrumental if one’s inaction makes S more likely to obtain. The distinction between positive and negative instrumentality becomes irrelevant in that both create the conditions such that S obtains. To deny this would be to deny that, when faced with a situation in which one can move or remain still and knowing that one’s staying still could prevent S from obtaining, one has relevant responsibility for one’s choices. I argue that this position is untenable. Where does this leave us so far? There is no distinction between negative and positive rights as such, but between negative and positive duties corresponding to those rights. Negative and positive duties are distinguished by negative and positive instrumentality. Negative and positive instrumentality that result in state of affairs S obtaining are equally morally important. Therefore, negative and positive duties attached to rights are equally morally important. Furthermore, then, violation of negative duties becomes as morally important as violation of positive duties, and the libertarian dichotomy between negative and positive rights, upon which Nozick’s critique depends, falls. What does this do for someone interested in equality? It is a well known fact that African Americans, throughout their history, have had their rights de facto violated and de jure legally unrecognized for most of their history in America. During the Jim Crow period, African Americans had differentially applied rights, both de jure and de facto, and concerning both negative and positive duties which correspond to human rights. Post Jim Crow, African Americans had their rights (or at least the negative duties attached to them) de jure respected, but remained de facto violated, a fact which is overtly evident in consideration of the gaps between African Americans and Caucasian Americans in terms of (to name a few) proportion of the prison population, average income, educational statistics, etc. Why, in changing from a state of affairs where rights were differentially applied to a state where negative rights were equally de jure fulfilled, did equality not follow? Negative duties prevent active violation of rights through action, and positive duties prevent passive violation of right through inaction. Positive duties also engage the active respect of rights, for example, by maintaining social systems to satisfy and protect such rights, and working to maintain the satisfaction of these rights themselves. Negative duties are useful to prevent further active violations of rights, but as their fulfillment consists of omissions instead of actions, they structurally cannot be useful to remedy past offenses. Moving from a previous state where rights were de jure or de facto violated requires fulfillment of both negative (to prevent further active violations) and positive (to move from the previous state of where rights were violated to a state where rights were fulfilled, and to prevent further inactive violations) duties. Post-Jim Crow inequality and differential de facto fulfillment of rights obtained because (1) systemized inequality in the application of rights (either de jure or de facto) requires for its fulfillment of both negative and positive duties (which, to be fulfilled, must bring past victims of inequality up to equal to be fulfilled), (2) in the absence of which rights remain unfulfilled. In short, remediation of past and present inequality requires the realization of positive duties in the political, civil, social, cultural, and economic realms. Three observations follow from the proceeding discussion. First, I would like to reiterate following our Jim Crow discussion that any legalization of a state of affairs that systematically inhibits equal opportunity or power in an area that the fulfillment of rights depends upon systematically violates rights, and thus for the future fulfillment of rights, must be returned to its pre-systemization state of affairs. This will become important a little later. Second, of one accepts the Lockean set of basic rights, and interprets rights as Nozick does as absolute, inviolable side constraints, and recognize positive duties in addition to solely negative duties, then (regarding these basic rights) there is an absolute duty to fulfill both the negative and the positive duties, as far as possible, included as a side constraint upon action. For example, take the ‘right to life’ side constraint—every action, without fail, must both refrain from actions that take away the life of another, AND every action, without fail, must promote the lives of everyone for whom promotion is possible. Finally, whereas the collapse of the distinction between positive and negative rights and equality between negative and positive instrumentality allow Du Bois’ more expansive rights program, positive rights to life and liberty require a more expansive social, cultural, and economic rights system like Du Bois’ rights system for their complete fulfillment. Consequently, the collapse of the distinction between negative and positive rights secures Du Bois’ program for racial equality. Finally, I would like to examine an earlier observation in order to look more in depth at Du Bois’ socioeconomic goals in his struggle for socialism. The two most common and essential characteristics of a socialist economy are (1) the public ownership of the means of production, or in other words, of that which generates and controls wealth, and (2) some degree of equalization along some measurement of wealth, goods, power, and/or services. Of Du Bois’ ten socioeconomic goals, (1) is the first characteristic of a socialistic economy, while (2) through (9) (and possibly 10 depending on the implications of dogmatic religion on equality in these categories) involve equality in social wealth, goods, power, and services, or principle (2) of socialism3. The case for socialism largely hinges on socialist principle (1), being commonly considered the precondition for (2)4. Thus, the socialist case hinges upon whether or not an individual has a right to privately owned capital, or more generally, whether or not privately owned capital hinders or is protected by rights. 3 (3) involves equalization of wealth. (2) and (5)-(7) involve equalization among services. (4), (8) and (9) involve equalization of power (and, for that matter, (1) and possibly (10)). 4 Even if equalization of wealth and services were achieved, say through taxation, with maintenance of private ownership of capital (say, in a welfare capitalist state), it can easily be argued that equality of power would not be. First, let’s take the commonly held position that all people have inalienable rights to private property in general. To simplify things (and perhaps give those who think we have only a negative right to private property perhaps a stronger case), let’s assume only a negative conception of property rights, and not look at implications of a positive interpretation of property rights. I will maintain, however, the implications of our earlier discussion of the distinction between positive and negative rights as it pertains to establishing both types of interpretations of the right to life—e.g. both sustenance and security interpretations. I want to see if private ownership of property can conflict with the right to life—and as I take the right to life to be both prior to and more important than property rights, I assume the right to life will win out in case of a rights conflict. General maintenance of private property rights does no damage to the right to life—it is only with the goods that the right to life requires (like food, housing, etc., or the wealth necessary to obtain such goods) and uses of property that kill that private property rights can interfere with the right to life. Withholding food from the starving, for example, is a violation of sustenance rights. Ownership of these goods, or the means to attain them, are subject to usage rules so constrained by rights, then, that property rights in these goods are very limited, if existent at all. At rough levels of equality of goods, then, holdings would remain the same, but at unequal levels would be regulated against. The distributors of these goods, however, are the owners of capital—the means by which these goods are produces, and by which wealth is generated. Holding both the negative and positive interpretations of rights as solid, any distributive standard that distributes sustenance goods in a manner other than according to need, or furthermore, produces anywhere short of that which can provide universal sustenance, where technologically possible, violates rights. The primary condition applies to each owner of capital individually, and the latter to the class as a whole. In short, in order for the distribution of sustenance goods and income to be secure enough such that rights are universally fulfilled, absolute constraints would have to be put on capital use, such that substantial capital ownership would not exist. Private ownership of capital would be completely formal—and in effect, since use of capital would be wholly determined by forces outside of the capitalist, it would be a meaningless gesture to say the capitalist has ownership of capital. Finally, the choice whittled down between private, but completely constrained, ownership of capital, and social ownership of capital, despite the lack of practical difference, would there be a right to private capital ownership, all-things-considered? Let us revisit my argumentation following the Jim Crow example—any legalization of a state of affairs that systematically inhibits equal opportunity or power in an area that the fulfillment of rights depends upon systematically violates rights, and thus for the future fulfillment of rights, must be returned to its pre-systemization state of affairs. Private ownership of capital was saved from being a pure, all-things-considered violation of rights only through completely controlling its use. Capital ownership would be purely formal, and as a general theme of this paper shows (I hope), if something is purely formal and without substance (such as the fulfillment of rights), it isn’t, or to be clearer, something either is in substance, or is not at all, and something cannot be fulfilled “in form but not in substance.” Privately owned but completely socially controlled capital has too many conditions of ownership taken away to be private ownership, and to be any other way is to systematically inhibit equal opportunity and power in the most important right, the right to life. In short, private ownership of capital violates rights, and thus there can be no private ownership of capital. The Du Boisian project for racial and socioeconomic equality hinges upon a conception scheme of both positive and negative rights. The libertarian critique of the notion of positive rights would work against both the positive rights Du Bois outlines (in addition to positive interpretations of basic rights) and against his struggle for socioeconomic equality. I have responded by showing the collapse of the distinction, and then showing why negative interpretations of rights were inadequate for remedying past systematic inequalities, such as racism. This leads to a reapplication of the new structure of rights to the topics of racial and socioeconomic equality in order to support Du Bois’ programs for each. For achievement of socioeconomic equality, the application of such a structure of rights necessitates social ownership of capital. With the brush cleared, we can finally walk the Du Boisian path to a more equal world. Works Cited Bennett, Jonathan. "Morality and Consequences." The Tanner Lectures on Human Values 1980 47-116. 05/03/2008 <http://www.tannerlectures.utah.edu/lectures/documents/bennett81.pdf> Du Bois, W. E. B. "Application for Membership in the Communist Party of the United States of America." W. E. B. Du Bois: A Reader. Ed. David Levering Lewis. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1995. pp 631-33. -----. "My Evolving Program for Negro Freedom." W.E.B. Du Bois: A Reader. Ed. David Levering Lewis. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1995. pp 610-18. -----. "There Must Come a Vast Social Change in the United States." W. E. B. Du Bois: A Reader. Ed. David Levering Lewis. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1995. pp 619-21. Nozick, Robert. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. Basic Books, Inc., 1974. Shue, Henry. "Rights in the Light of Duties." Human Rights and U.S. Foreign Policy. Ed. Brown, Peter G. and Douglas MacLean. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, 1979. pp. 65-81.