Russian Pearl

advertisement

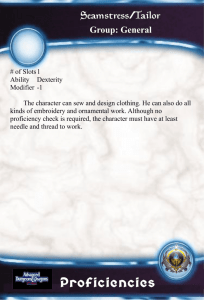

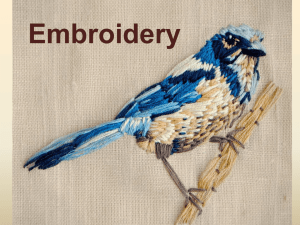

RUSSIAN PEARLEMBROIDERED HEADDRESS FOR AN UNMARRIED WOMAN Late 15th-Early 17th Centuries Documentation for an entry presented at Pentathlon in Caid 2007 Entrant # 115 Summary Foreign travelers to Russia in the XVIth- XVIIth centuries such as German Adam Olearius, Englishman Sir Giles Fletcher, and Frenchman Jacques Margeret all commented in their notes on Russians’ love for pearl embroidery on all kinds of clothes, from boots to hats (quoted in Iakunina, see below for details). Archbishop Arsenii Elassonis describes the opulence of Tsaritsa Irina Fedorovna outfit (1588-1589), that included a crown adorned with gems and pearls. Surviving examples of ecclesiastical wear and rare secular items, as well as wills and other period documents also attest to widespread use of pearls in garment decoration. Iakunina cites wills that refer to pearl embroidered voshvy (cuffs for a letnik*, a loose light dress with wide triangular sleeves), hats, collars, and other items. Thus, the presented headdress utilizes pearl embroidery based both on surviving period examples of pearled garments and post-period examples of similar headdresses. The technique for late period pearl embroidery is described in detail by Iakunina, who made an extensive study of artifacts and archive documents virtually inaccessible from outside of Russia. Available photographs, such as those of items from Zagorsk Museum Collection in Manushina’s book (Appendix), provide for better understanding of the technique. First, an embroiderer (usually a woman in a workshop or at home) or a special artist would draw a pattern onto fabric with chalk, coal, or ink. Then, that pattern was outlined in “bel’ “ –single or double line of white cord (cotton or linen) or thick white threads (cotton or linen). Bel’ was used since at least early XVth century as foundation for pearl embroidery. Pearls were sorted and gathered on long, strong linen or silk thread that was then wound up on a special wand. After these preparations, the pearled thread was laid over the foundation and couched down with another white thread after every single pearl, with stitches going through the foundation and the pearled thread pulled very taught. Finally, the pearl embroidery was outlined in twisted gold cord, with stitches in silk thread going through the gold cord and through the foundation. Pearl embroidery on the presented headdress was done in the described technique, using freshwater pearls. The foundation was a double line of white cotton yarn. A synthetic gold cord was used, because it resembled in appearance some period examples and because the real thing would be unaffordable. Rayon thread in “gold” was used instead of silk thread to secure the gold cord. The embroidery is done on silk velvet, which, according to Giliarovskaia, was available in Russia during the time in question. Indeed, many items from Zagorsk Museum Collection (Manushina) were worked on simple velvet, often red (see Appendix). More details on period technique and the execution of the presented embroidery appear below. Ornamental motives on embroideries of the XVIth century are mostly floral or floral-geometric. Foliage, flowering stylized trees, S-shaped lines, diamonds, circles, and crosses abound on the pieces from Zagorsk Museum Collection (Appendix). These design elements are very similar to those found on other forms of period applied art. For the presented embroidery, a pattern was adapted from a XIII-XIVth century metal filigree cross (Postnikova-Loseva, #29). This choice was made because the lady who will wear this hat preferred Novgorod designs with hearts, and no period embroideries with such patterns could be found. ________________________________________________________________________ * Russian terms are italicized throughout Russian Pearl Embroidery Embroidered Garments Very little survives of Russian pre-XVIIIth century secular pearl embroidery, though examples of ecclesiastical pearl embroidery are more numerous. Various documents, such as wills and property registers, recount items such as letnik (a loose dress with large triangular sleeves) cuffs, hats and headdresses, collars, and other garments that were adorned with pearls and gold (as cited in Iakunina, Rabinovich, and Giliarovskaia). For example, in 1328 the Grand Duke of Moscow, Ivan Kalita, listed in his will several pearled kozhuhi (outer garments with fur on the inside) as well as “large belt with pearls and gemstones,” while the father of the Grand Duke Dmitriy Donsky (late XIIIth century) left his sons “opashen’ red, pearled” (as cited in Iakunina, p. 60). Later, in 1486, Prince Mikhail Vereiskii left upon his death several collars embroidered with pearls and adorned with gems, matching cuffs for some of them, pearled shirts, and a pearled ubrus (long rectangular head covering for married women) (Iakunina, pp. 6465). Later yet, in 1503, the will of Princess Iuliana Volotskaia lists collars, shirts, shuby (cloth-covered fur coats), and a hat all adorned with pearl embroidery and pearl netting (Iakunina, pp. 68-69). Likewise, foreign visitors to Russia noticed the Russians’ love for pearls and a tendency to embroider with pearls all kinds of garments. The Englishman Sir Giles Fletcher, who visited Russia during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, described head coverings, hats, collars, dresses, and even boots with pearl embroidery (Iakunina, p. 69). Similarly, the French officer Jacques Margeret, who lived in Moscow from 1590 to 1606, recounts that he saw “up to fifty royal garments embroidered instead of trim with precious ornamentation, saw clothes sewn with pearls from top to bottom or for a foot, half a foot, and about four fingers all around, about half a dozen throws covered with pearls, and other such things” (as cited in Iakunina, p. 71). He also mentions that even everyday headwear, men’s and women’s, was richly embroidered with pearls. An example of such headwear, and ubrus that belonged to Tsaritsa Anastasiia Romanovna, wife of Ivan the Terrible (XVIth century), was made of scarlet taffeta 2 meters long. In the front middle part it is adorned with blue silk damask rectangle, 40 cm long and 16 cm wide. This rectangle, “ochel’ie,” is richly embroidered in pearls and gold with enameled inserts. The embroidery runs along the main body of the ubrus towards its ends. The ends themselves are trimmed with the endings made of 36.5 cm of the same fabric with slightly different embroidery (Iakunina, p. 74 and Figure 32). Unfortunately, my source does not allow establishing the width of the ubrus. Iakunina also provides numerous examples of post-period headwear adourned with pearl embroidery, and cites wills and other documents mentioning such headwear during XVIth-XVIIth centuries. Thus, it was justifiable to use pearl embroidery on this maiden’s headdress. The headdress was made for use by a noblewoman and represents Russian fancy dress for the nobility of the late XVIth-early XVIIth centuries. Materials Red silk velvet, similar to that used for 1550 shroud with the Cross (Item 31, see Appendix) Freshwater pearls in various sizes Glass cabochons imitating emeralds Base metal gold-tone cabochon settings Silver, gold plated plaques with embedded garnets (provided by the intended wearer). “Gold” cord similar in appearance to that used for 1595 phelonion (Item 35, see Appendix) White cotton yarn for the foundation White all-purpose thread White nylon beading thread (used for strength) Gold colored rayon thread (substitution for silk thread) Millinery materials: buckram, millinery wire, flannel, grosgrain ribbon. Embroidery Technique In XVIth-XVIIth centuries in Russia, embroidery was an exclusively womanly pursuit, and one of the most complex things a woman could work at. Most surviving embroideries came from either monastery or private workshops, though some were produced to order by independent workers (Iakunina, p. 51). First, depending on the complexity of the pattern, either the embroiderer herself or a special artist known as “znamenshchik” (usually male) would draw it onto the chosen fabric with chalk, coal, or ink. Since I am not certain of my drawing, I begin by making a pattern on paper and transferring it to iron-on interfacing, which I use to stabilize the fabric. In period, according to Iakunina (p. 45), flour paste was used for the same purpose. Experienced embroiderers prepared the paste using secret recipes, now lost (the paste they made was not prone to be eaten by bugs), though it was basically just flour mixed with water or kvas and simmered until ready. The paste was spread on the back of the embroideries by hand while still stretched tight on the frame, to prevent it from puckering after removal. Since my embroidery is not subjected to such treatment, it does pucker a little. The next step in this project was transferring of the pattern to the front of the work. This was done by sewing through it with white thread in running stitch. That thread becomes completely covered by later work. Before laying out the pearls, period embroiderers usually laid out a foundation of white cord or thick threads, in single or double line (Iakunina, p. 35). A shroud “Cross at the Golgopha” from Zagorsk Museum collection, dated to 1550, clearly shows the lines of couched white cord where the pearls had been removed (Appendix A, from Manushina). Such linen or cotton cord or threads, known as bel’ was used since at least early XVth century as foundation for pearl embroidery, as evidenced from documents. For example, Iakunina (p.35) quotes a 1509 will that listed pearl embroidery on various items made “na beli” (over the foundation). For this project, I used white 100% cotton yarn, doubled. After the pattern was prepared, the yarn was couched down with strong white thread everywhere there was to be pearl embroidery. In period, pearls meant for embroidering were sorted according to size and quality and gathered on a long thread using a needle. The thread was then wound around a special wand (“viteika”) which was used to store the pearls and to keep the thread taught during embroidering (Iakunina, pp. 37-37, fig. 15). Most readily available were freshwater pearls from Russian rivers, but the most valued were imported Persian pearls (Iakunina, p. 26). Most surviving embroideries were done with relatively small, oval or potato-shaped pearls drilled horizontally (e.g., photos in Appendix). The hat presented here was made to fulfill a promissory, and due to time pressure I had to use the fresh water pearls that were easily available at the time, which were rice-shaped pearls drilled vertically. Once a viteika with the pearled thread was prepared, the end of the thread was taken with a needle to the back of the fabric at the beginning of the foundation, and secured there with a knot (Iakunina, p. 38). Then, it was laid along the pattern and couched with a different white thread, silk or linen, with stitches after every single pearl going into the foundation. The pearled thread and the couching thread were pulled very taught, so that when pearls on some embroideries were lost or removed later, one could count how many there were by indentations (Iakunina, p. 41). I used this technique for the presented headdress as well, though without utilizing a viteika. Instead, I gathered as many pearls on a separate thread with a beading needle as I needed for a continuous design element. I used nylon beading thread to ensure that the embroidery could stand up to SCA wear. Finally, pearl embroidery was outlined with gold cord, usually twisted. Embroideries in Appendix A, such as 1592 phelonion and, on which such cord is clearly visible evidence this, showing how gold cord both hid the foundation and enhanced the overall effect. That cord was not secured by couching over it, but sewn to the foundation with the stitches going through the middle of the gold cord and into the edge of the foundation (Iakunina, p. 42). Since pearl embroideries were highly valuable, this technique allowed saving the complete embroidery if the background fabric wore out by cutting it out whole and appliquéing it to another fabric. Since real gold cord is beyond my means, I used a synthetic cord which resembles the way period cords were made. Unfortunately, it is too thin compared to the proportion of most period cord used for embroidery, but a slightly thicker cord of comparable quality could not be located. This cord was also couched alone to make the design stand out better from the distance and due to time constraints on the commissioned work. Phelonion dated between 1641 and 1674 and a 1635 sticharion in Appendix illustrate how this was done for small details. The embroidery technique used for this entry can be further illustrated by sample embroidery (future pouch) provided here, which shows all stages of the process. The sample uses a single row of white yarn instead of a double row, and a different gold cord (no longer available for sale). Embroidery Design As seen on the photographs from the Zagorsk Museum collection (Appendix, from Manushina) and as analyzed by Manushina, a Russian expert on period embroidery, ornamental motives on embroideries of the XVIth century were mostly floral or floralgeometric. Foliage, flowering stylized trees, S-shaped lines, diamonds, circles, and crosses abound on the surviving ecclesiastical pieces. These design elements are very similar to those found on contemporary illuminations. Though there are no surviving Novgorod embroideries, illuminations such as those found in Medieval Russian Ornament (see cover page) or in other forms of applied art show heart-shaped motifs. For the presented embroidery, a pattern was adapted from a XIII-XIVth century metal filigree cross (PostnikovaLoseva, #29). This choice was made because the headdress was made to fulfill a promissory to a lady who was very fond of this particular pattern. Though that particular cross is earlier than the embroidery technique, similar motifs occur on virtually every other Novgorodian filigree in Postnikova-Loseva’s publication. The cross was traced to identify the elements of the pattern, which were then rearranged into an appropriate shape and modified for pearl embroidery (line spacing, gem placement, etc.) References Giliarovskaia, N. V. Russkii istoricheskii kostium dlia stseny. (Russian historic costume for the stage) Iskusstvo, Moscow, 1945. Iakunina, L. I. Russkoie Shit’ie Zhemchugom (Russian Pearl Embroidery). Iskusstvo, Moscow, 1955. Ivanova, O. Y. (ed.) Rossia XVII Veka v Vospominaniyah Inostrantsev. (Russia of 17Th century in memoirs of the foreigners). Rusich, Smolensk, 2003. Manushina, T. Early Russian Embroidery in the Zagorsk Museum Collection. Sovetskaia Rossiia, Moscow, 1983. Medieval Russian Ornament in Full Color from Illuminated Manuscripts. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1994. Postnikova-Loseva, M. Russian Gold and Silver Filigree. Isskustvo, Moscow, 1981. Appendix