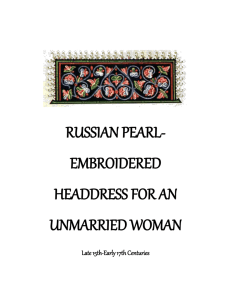

Pearl Embroidered Ensemble

advertisement

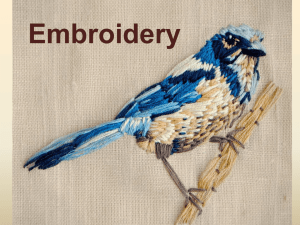

Russian Pearl-Embroidered Ensemble:Cuffs, Collar, and Hat Late XVIth-Early XVIIth Centuries Documentation for an entry presented at Pentathlon in Caid 2001 Entrant # 10 Summary Foreign travelers to Russia in the XVIth- XVIIth centuries such as German Adam Olearius, Englishman Sir Giles Fletcher, and Frenchman Jacques Margeret all commented in their notes on Russians’ love for pearl embroidery on all kinds of clothes, from boots to hats (quoted in Iakunina, see below for details). Archbishop Arsenii Elassonis describes the opulence of Tsaritsa Irina Fedorovna outfit (1588-1589), that included a crown adorned with gems and pearls. Surviving examples of ecclesiastical wear and rare secular items, as well as wills and other period documents also attest to widespread use of pearls in garment decoration. Iakunina cites wills that refer to pearl embroidered voshvy (cuffs for a letnik*, a loose light dress with wide triangular sleeves), hats, collars, and other items. Likewise, Manushina notes that pearled voshvy from letniki donated to churches and monasteries often ended up on ecclesiastical robes. She provides a picture of one such garment, a 1630s phelonion (Appendix A). Thus, an ensemble presented here** utilizes pearl embroidery on the cuffs, collar, and a hat that is meant to be worn inside a crown or a coronet, thus creating a Russian “koruna” – a Tsaritsa’s headdress (Giliarovskaia, ill. 242, from a contemporary drawing). The technique for late period pearl embroidery is described in detail by Iakunina, who made an extensive study of artifacts and archive documents virtually inaccessible from outside of Russia. Available photographs, such as those of items from Zagorsk Museum Collection in Manushina’s book (Appendix A), provide for better understanding of the technique. First, an embroiderer (usually a woman in a workshop or at home) or a special artist would draw a pattern onto fabric with chalk, coal, or ink. Then, that pattern was outlined in “bel’ “ –single or double line of white cord (cotton or linen) or thick white threads (cotton or linen). Bel’ was used since at least early XVth century as foundation for pearl embroidery. Pearls were sorted and gathered on long, strong linen or silk thread that was then wound up on a special wand. After these preparations, the pearled thread was laid over the foundation and couched down with another white thread after every single pearl, with stitches going through the foundation and the pearled thread pulled very taught. Finally, the pearl embroidery was outlined in twisted gold cord, with stitches in silk thread going through the gold cord and through the foundation. Pearl embroidery on the presented ensemble was done in the described technique, using freshwater pearls (see Figure 1). The foundation is a single line of white upholstery cord (probably polyester). A synthetic gold cord was used, because it resembled in appearance some period examples and because the real thing would be unaffordable. Rayon thread in “gold” was used instead of silk thread to secure the gold cord. Jewels in gold bezel settings were commonly incorporated in period embroideries, and were substituted here by fake cabochons in rhinestone settings. The embroidery is done on cotton velvet, which, according to Giliarovskaia, could have been available in late XVIth century Moscow. More details on period technique and the execution of the presented embroidery appear below. Ornamental motives on embroideries of the XVIth century are mostly floral or floral-geometric. Foliage, flowering stylized trees, S-shaped lines, diamonds, circles, and crosses abound on the pieces from Zagorsk Museum Collection (Appendix A). These design elements are very similar to those found on contemporary illuminations. For the presented embroidery, a pattern was adapted from a XVIth century illumination from a gospel book found in Medieval Russian Ornament in Full Color from Illuminated Manuscripts (Appendix B). ________________________________________________________________________ * Russian terms are italicized throughout ** The letnik itself was not made by the entrant, but by THL Arianna Kateryn Nunneschild Russian Pearl Embroidery Embroidered Garments Very little survives of Russian pre-XVIIIth century secular pearl embroidery, though examples of ecclesiastical pearl embroidery are more numerous. Various documents, such as wills and property registers, recount items such as letnik (a loose dress with large triangular sleeves) cuffs, hats and headdresses, collars, and other garments that were adorned with pearls and gold (as cited in Iakunina, Rabinovich, and Giliarovskaia). For example, in 1328 the Grand Duke of Moscow, Ivan Kalita, listed in his will several pearled kozhuhi (outer garments with fur on the inside) as well as “large belt with pearls and gemstones,” while the father of the Grand Duke Dmitriy Donsky (late XIIIth century) left his sons “opashen’ red, pearled” (as cited in Iakunina, p. 60). Later, in 1486, Prince Mikhail Vereiskii left upon his death several collars embroidered with pearls and adorned with gems, matching cuffs for some of them, pearled shirts, and a pearled ubrus (long rectangular head covering for married women) (Iakunina, pp. 6465). Later yet, in 1503, the will of Princess Iuliana Volotskaia lists collars, shirts, shuby (cloth-covered fur coats), and a hat all adorned with pearl embroidery and pearl netting (Iakunina, pp. 68-69). Likewise, foreign visitors to Russia noticed the Russians’ love for pearls and a tendency to embroider with pearls all kinds of garments. The Englishman Sir Giles Fletcher, who visited Russia during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, described head coverings, hats, collars, dresses, and even boots with pearl embroidery (Iakunina, p. 69). Similarly, the French officer Jacques Margeret, who lived in Moscow from 1590 to 1606, recounts that he saw “up to fifty royal garments embroidered instead of trim with precious ornamentation, saw clothes sewn with pearls from top to bottom or for a foot, half a foot, and about four fingers all around, about half a dozen throws covered with pearls, and other such things” (as cited in Iakunina, p. 71). He also mentions that even everyday headwear, men’s and women’s, was richly embroidered with pearls. An example of such headwear, and ubrus that belonged to Tsaritsa Anastasiia Romanovna, wife of Ivan the Terrible (XVIth century), was made of scarlet taffeta 2 meters long. In the front middle part it is adorned with blue silk damask rectangle, 40 cm long and 16 cm wide. This rectangle, “ochel’ie,” is richly embroidered in pearls and gold with enameled inserts. The embroidery runs along the main body of the ubrus towards its ends. The ends themselves are trimmed with the endings made of 36.5 cm of the same fabric with slightly different embroidery (Iakunina, p. 74 and Figure 32). Unfortunately, my source does not allow establishing the width of the ubrus. Collars, or “ozherel’ia,” were either woven as pearl netting, or, more commonly, made of rich fabric embroidered with pearls. Iakunina (p. 80) cites a 1615 document that describes “collar sewn over white satin with dome-shaped pearls, 145 pearls in all.” Some such collars were standing, and some were round. The later were known as “diadimy,” or, in royal wardrobe, “barmy” (Giliarovskaia, ill. 172). Another popular place for pearl embroidery was on letnik cuffs, known as “voshvy,” that were often kept separately and attached to different dresses (Giliarovskaia, p. XX, ill. 44 taken from the album of Meyerberg, an ambassador to Russia). An early XVIIth century description of a letnik that belonged to Tsaritsa Evdokiia Lukianovna mentions “voshvy of red velvet sewn with pearl eagles and unicorns, with gold and stones” (Iakunina, p. 82). Thus, it was justifiable to adorn with pearl and gold embroidery voshvy for a letnik, a round collar-barmy, and a hat that is meant to be worn inside a crown or a coronet like a Russian “koruna” – A Tsaritsa’s headdress (Giliarovskaia, ill. 242, from a contemporary drawing). This ensemble was made for royal use and represents Russian fancy dress for the nobility of the late XVIth-early XVIIth centuries. Embroidery Technique In XVIth-XVIIth centuries in Russia, embroidery was an exclusively womanly pursuit, and one of the most complex things a woman could work at. Most surviving embroideries came from either monastery or private workshops, though some were produced to order by independent workers (Iakunina, p. 51). First, depending on the complexity of the pattern, either the embroiderer herself or a special artist known as “znamenshchik” (usually male) would draw it onto the chosen fabric with chalk, coal, or ink. Since I am not certain of my drawing, I begin by making a pattern on paper and transferring it to iron-on interfacing, which I use to stabilize the fabric (Figure 1a,b*). In period, according to Iakunina (p. 45), flour paste was used for the same purpose. Experienced embroiderers prepared the paste using secret recipes, now lost (the paste they made was not prone to be eaten by bugs), though it was basically just flour mixed with water or kvas and simmered until ready. The paste was spread on the back of the embroideries by hand while still stretched tight on the frame, to prevent it from puckering after removal. Since my embroidery is not subjected to such treatment, it does pucker a little. Though not shown in the photographs, the next step in this project was transferring of the pattern to the front of the work. This was done by sewing through it with white thread in running stitch. That thread was removed once the work was completed. Before laying out the pearls, period embroiderers usually laid out a foundation of white cord or thick threads, in single or double line (Iakunina, p. 35). A shroud “Cross at the Golgopha” from Zagorsk Museum collection, dated to 1550, clearly shows the lines of couched white cord where the pearls had been removed (Appendix A, from Manushina). Such linen or cotton cord or threads, known as bel’ was used since at least ________________________________________________________________________ * Photographs in Figure 1 are from a different project, a “kokoshnik” headdress, which was made using the same technique. Regrettably, no photographs were taken during the making of the presented ensemble. early XVth century as foundation for pearl embroidery, as evidenced from documents. For example, Iakunina (p.35) quotes a 1509 will that listed pearl embroidery on various items made “na beli” (over the foundation). After trying various possibilities – different kinds of cord and cotton yarn – I chose to work with synthetic upholstery cord (#50) which provides best stability for the pearls. After the pattern was prepared, this cord was couched down with strong white thread everywhere there was to be pearl embroidery (Figure 1c). In period, pearls meant for embroidering were sorted according to size and quality and gathered on a long thread using a needle. The thread was then wound around a special wand (“viteika”) which was used to store the pearls and to keep the thread taught during embroidering (Iakunina, pp. 37-37, fig. 15). Most readily available were freshwater pearls from Russian rivers, but the most valued were imported Persian pearls (Iakunina, p. 26). Most surviving embroideries were done with relatively small, oval or potato-shaped pearls drilled horizontally (e.g., photos in Appendix A). The ensemble presented here was commissioned from me, and thus embroidered with the provided pearls, which were rice-shaped and baroque freshwater pearls, drilled vertically. Once a viteika with the pearled thread was prepared, the end of the thread was taken with a needle to the back of the fabric at the beginning of the foundation, and secured there with a knot (Iakunina, p. 38). Then, it was laid along the pattern and couched with a different white thread, silk or linen, with stitches after every single pearl going into the foundation. The pearled thread and the couching thread were pulled very taught, so that when pearls on some embroideries were lost or removed later, one could count how many there were by indentations (Iakunina, p. 41). I used this technique for the presented ensemble as well, though without utilizing a viteika. Instead, I gathered as many pearls on a separate thread with a beading needle as I needed for a continuous design element (Figure 1d,e). I used nylon beading thread to ensure that the embroidery could stand up to SCA wear. Finally, pearl embroidery was outlined with gold cord, usually twisted. Embroideries in Appendix A, such as 1592 phelonion and, on which such cord is clearly visible evidence this, showing how gold cord both hid the foundation and enhanced the overall effect. That cord was not secured by couching over it, but sewn to the foundation with the stitches going through the middle of the gold cord and into the edge of the foundation (Iakunina, p. 42). Since pearl embroideries were highly valuable, this technique allowed saving the complete embroidery if the background fabric wore out by cutting it out whole and appliquéing it to another fabric. Since real gold cord is beyond my means, I used a synthetic cord which resembles the way period cords were made (Figure 1f). This cord was also couched alone to make the design stand out better from the distance and due to time constraints on the commissioned work. Phelonion dated between 1641 and 1674 and a 1635 sticharion in Appendix A illustrate how this was done for small details. In addition to pearl and gold embroidery, the “koruna” hat is decorated with bezel set fake cabochons and a metal rose. Gems in such settings were often a part of pearl embroideries, as evidenced by the “Trinity” purificator (1598-1604) and 1635 sticharion in Appendix A. According to Gilarovskaia, a koruna could be topped by a large gem or a cross. Here, the metal rose was provided by the commissioner, and was used to top the hat since it was fitting to place a gold rose on a royal peer’s hat. Metal plaques, though usually of simple geometric shapes, were often incorporated in the pearl embroideries (Appendix A), so such use of the metal rose was justifiable. Embroidery Design As seen on the photographs from Zagorsk Museul collection (Appendix A, from Manushina) and as analyzed by Manushina, a Russian expert on period embroidery, ornamental motives on embroideries of the XVIth century were mostly floral or floralgeometric. Foliage, flowering stylized trees, S-shaped lines, diamonds, circles, and crosses abound on the surviving ecclesiastical pieces. These design elements are very similar to those found on contemporary illuminations. For the presented embroidery, a pattern was adapted from a XVIth century illumination from a gospel book found in Medieval Russian Ornament in Full Color from Illuminated Manuscripts (Appendix C) References Giliarovskaia, N. V. Russkii istoricheskii kostium dlia stseny. (Russian historic costume for the stage) Iskusstvo, Moscow, 1945. Manushina, T. Early Russian Embroidery in the Zagorsk Museum Collection. Sovetskaia Rossiia, Moscow, 1983. Medieval Russian Ornament in Full Color from Illuminated Manuscripts. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1994. Iakunina, L. I. Russkoie Shit’ie Zhemchugom (Russian Pearl Embroidery). Iskusstvo, Moscow, 1955. Appendix A Appendix B