AMY COHEN, ET AL

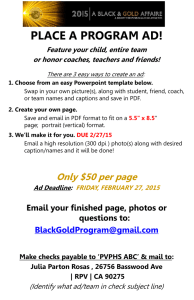

advertisement