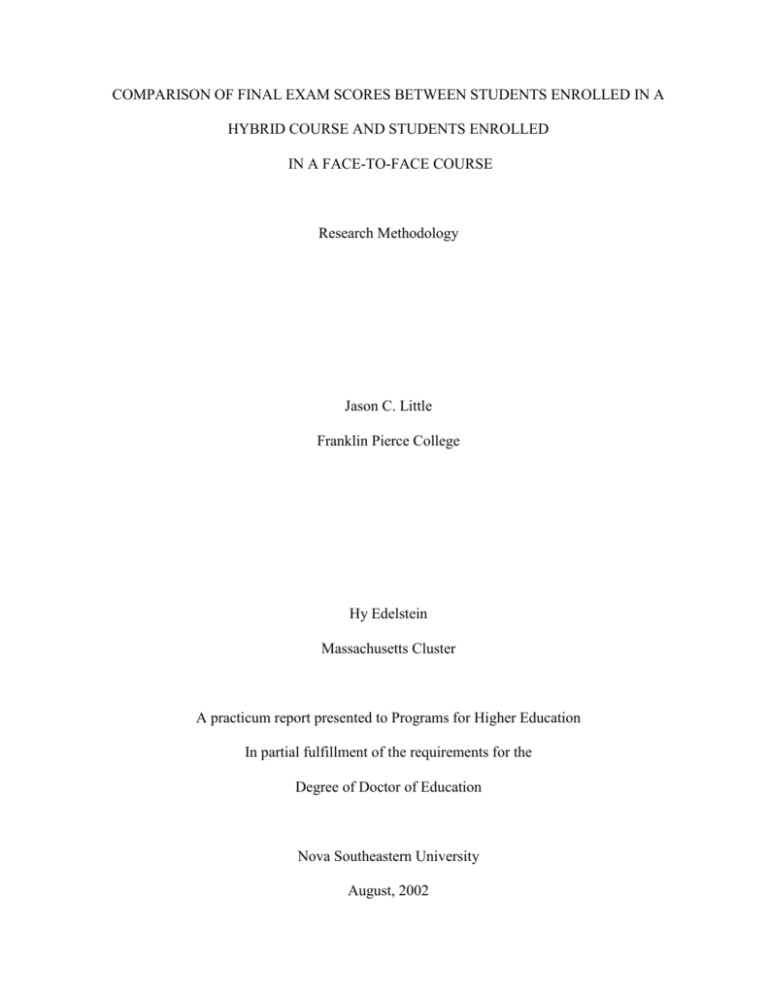

practicumreportresearch

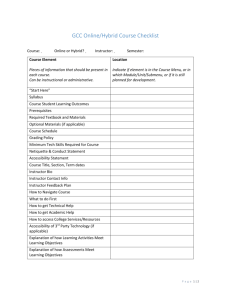

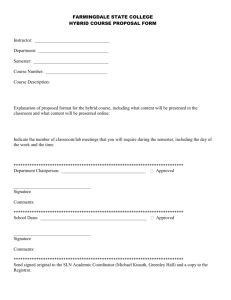

advertisement