Richards, The Language Teaching Matrix p71-71

advertisement

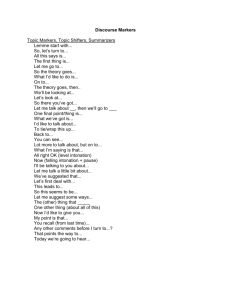

Use cohesive devices (ellipsis, substitution, reference) to make this spoken text more natural-sounding: Tom and Nick are neighbours (Tom rings Nick’s door bell) Tom: Can I borrow your lawnmower please? Nick: Why do you want to borrow my lawnmower? Tom: My lawnmower’s broken. Nick: Here is my lawnmower. I bought my first lawnmower when we moved to our present house in 1997. We’d lived in a flat before 1997 so we didn’t need a lawnmower. I love having a garden and pottering around in my garden. Tom: Thanks. Bye. Text with cohesive devices: (door bell rings) Tom: Can I borrow your lawnmower please? Nick: Why? Tom: Mine’s broken. Nick: Here it is. I bought my first lawnmower when we moved here in 1997. We’d lived in a flat before that so we didn’t need one. I love having a garden and pottering around in it. Tom: Thanks. Bye. Features of spoken English: Spontaneity: Unfinished or incomplete sentences Interruptions Repetitions Hesitations Filled pauses False starts and backtracking Utterances built up clause by clause connected by: and / but / so (co-ordination) Head slot – to announce topic of utterance e.g. Men, aren’t they funny? Tail slots – to comment / qualify / clarify utterance e.g. isn’t it? / actually / They’re funny aren’t they, men. Prefabricated lexical chunks Grammar mistakes due to lack of planning time Interactivity: Backchannelling to keep conversation going e.g. Yeah, Hmm Interruptions Turn-taking Overlapping turns Discourse markers – to signal speaker’s intention and show connections. Gesture, expression (paralinguistic features) Sentence stress and intonation carry meaning e.g. John may go / John may go. Repair – dynamic nature allows for negotiation of meaning - we adjust the message according to immediate feedback Interpersonality (to maintain solidarity): Vague language to avoid to sound less opinionated e.g. sort of / something / stuff Referral to shared knowledge Others may finish our sentences for us Informal style Question tags to invite agreement Coherence: Cohesive devices just as in written discourse e.g. substitution, reference and a lot of ellipsis. Topic consistency and co-operatively managed topic shift Macrostructure: o scripts o adjacency pairs o openings + closings o story sequences o deictic language (reference to immediate environment) e.g. it’s about this big / what’s that over there? SPOKEN DISCOURSE Compare the following 2 texts and decide what are some of the features that characterise spoken texts Written text – giving directions Go through the glass entrance doors and turn right. Walk to the corner and turn right again into Walker St. Walk along Walker St for four blocks until you come to Light St with the ANZ Bank on the corner. Turn left into Light St and continue to Francis St with the fruit shop on the corner. Cross to the other side of Light St and then cross over Francis St. Continue along Light St until you come to the Light Arcade. Go to the stairs at the back of the arcade and you’ll find the Medical Centre on the first floor above the coffee lounge. Spoken text - asking and giving directions A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: B: A: Um … give me an idea how I get to your place … I don’t … ’cos, I don’t, um, … know it too well this area. I’ll, uh … probably be coming by bus …so Right, well, going towards French Street, stay on the bus for, oh … about …the trip takes about twenty minutes by bus. Right. Fine. Now, the bus it’ll go out along St Katherine’s Road. Well, you … [just keep on the bus … [Mmm …hm … And it’ll cross over Peters Road which is fairly [major … [Yeah … I know Peters … Hm … now, you watch out for Minter Street. … It’s about … oooh, fifteen minutes by bus from the corner of Peters [I reckon … [Right … uh … a bit longer, maybe twenty depending on the traffic. …Um, now get off at the …um, South Weston post office, which I think is two stops … two stops past Minter Street. Right … that’s fine … Turn-taking and topic change A conversation is constructed fundamentally of people taking a series of turns to speak and then listen; turn-taking is concerned with how and when speakers take turns. It is an area that poses difficulty for students as the rules are complex and not always observed, and they are not necessarily transferable from one culture to another. Two of the basic rules of English turn-taking are, for example, not to interrupt and not to dominate the conversation; however, in many cases we are forced to interrupt if we want to take a turn, particularly in a large group discussion. We may also interrupt to mark anger, urgency, a need to correct something or disagreement. A further example has to do with long pauses and silence. These are considered inappropriate or ‘dispreferred’ in English, but silence is an acceptable aspect of conversation in Finland. Evidence collected regarding turn-taking indicates that participants know when one person is finishing a turn and signals to others that s/he is giving up the turn by: Using a discourse marker e.g. to summarise: ‘so that was that’ a facial expression or gesture eye contact (listener looks speaker in the eye, but speaker looks away until the end of the turn – so return of eye contact is an ‘end of turn’ signal) Intonation: a falling tone A lack of focus on this results in learners who may well have the linguistic ability to participate effectively in a conversation, but who are unclear about the conventions, and so they are reluctant to take part. Turns may be long or as short (as an adjacency pair), and learners need help identifying appropriate length. If someone takes too short a turn, they may appear to be bored by the topic; conversely, if they take too long a turn, they will appear rude, overbearing and boring. The issue of length is of course relative and the status of the speakers will affect the length of the turn which is considered acceptable. Typical discourse markers for managing turn-taking include: That reminds me (=I’m continuing on the same topic) By the way (=I’m indicating a topic change) Well anyway (=I’m returning to the topic) Like I say (=I’m repeating what I said before) Yes, but (=I’m indicating a difference of opinion) Yes no I know (=I’m indicating agreement with a negative idea) Signals that you are waiting for a turn: Increased quantity and volume of backchannelling Body language: tensing, leaning forward Conversational Repair The need for repair arises frequently in conversation: perhaps we haven’t heard or understood what someone has said; perhaps someone has misunderstood or misheard what we’ve said or we are not certain our listener(s) has understood what we’ve said; or, perhaps we’ve made a mistake in speaking and have to correct ourselves. Repair, then, is concerned with participants attempting to correct or deal with problems that arise in the course of a conversation. Van Lier (as quoted in Richards) emphasises that discourse involves: “ .....continuous adjustment between speakers and hearers obliged to operate in a code which gives them problems. This adjustment in interaction may be crucial to language development, for it leads to noticing discrepancies between what is said and what is heard, and to a resolution of these discrepancies ..... Repairing as one of the mechanisms of feedback ......is likely to be an important variable in language learning. Although it is not a sufficient condition, we may safely assume that it is a necessary condition.” Richards, The Language Teaching Matrix p71-71 Useful fixed expressions and sentence frames: Clarify what someone else said: Did you mean to say ...................? So you mean that........................ Are you saying............................? So the basic/general idea is........ Clarify what we said: What I’m saying is....................... Let me rephrase that. Let me put it another way............ Check someone is following the conversation: Are you with me? Do you see what I’m getting at? Am I making sense? Indicate you’re lost in the conversation: More or less, yes ............ Well, not really. Discourse markers Discourse markers are words or phrases that help us to structure and monitor a stretch of written or spoken language. They can: Focus on the listener, checking that s/he is following what is being said Make sure the speaker doesn’t sound too certain or dogmatic Focus on the speaker, helping him/her to structure what s/he is saying Some points about discourse markers: 1) Some of the most frequent discourse markers in spoken English are: okay, well, you know, I mean, actually, right, I think, ‘cos, so 2) Markers such as ‘right / OK / well / anyway / now’ normally occur at the beginning of utterances and indicate a boundary between one part of a conversation or one topic and another. 3) ‘Well’ and ‘I mean’ and ‘I think’ indicate that further comment and details will follow. 4) Markers such as you know’ check that your listener understands you and that you both share the same viewpoint. 5) Markers such as ‘I don’t know’ and ‘I think’ are sensitive to listeners and tend to soften opinions. 6) ‘oh’ – this is typically used either to launch an utterance or to respond to the previous speaker’s utterance, often with implications of surprise or unexpectedness. 7) ‘y’know’ – this marker serve to gain and maintain attention on the speaker by appealing to the hearer’s shared knowledge. Adjacency pairs A: Would you mind if I turn the volume down? B: Not at all. Paired utterances like this, in which the second is dependent on the first, are called adjacency pairs. Questions and answers are the most common form of adjacency pairs, but also greeting, requests, invitations etc. are typically realised by means of adjacency pairs. The second utterance can be the preferred response or the dispreferred response: A: What time is it? B: 10 o’clock (preferred response) / I’m sorry I haven’t got a watch (dispreferred response) A: Is this seat free? B: Yes (preferred response) / No, my friend’s sitting there (dispreferred response) Thus turn types include things like request-(non) compliance, greeting - greeting, offer acceptance / refusal, blame – denial / admission, question - (un)expected answer etc. While coursebooks and teachers are quite good are introducing adjacency pairs and providing students with practice, they are less good at preparing learners to cope with or to produce an unexpected dispreferred response. This results in students sticking to the ‘safe’ formula rather than saying what they may really feel/think; it also results in students potentially responding inappropriately to the unexpected response. Opening and closing Closing a conversation can present learners with difficulties. In British English we tend to negotiate the end of a conversation with phrases such as “Well it’s been nice…”, “Sorry, but I’ve got to run”, “Well, I’ve got to go now” etc. Problems arise when students are inappropriately formal or abrupt/direct in closing the conversation. Simply saying “Goodbye” rather than “I know there’s plenty more to say, but... ” creates an impression of rudeness. Longer sequences of adjacency pairs are also a feature of the openings and closings of conversations: A: B: A: B: Look at the time. I must get going. Oh god yeah. See you then. Yup. See you later. It is a common complaint of learners of English that it is not easy to open conversations with native speakers and, compared to some other cultures, this is possibly true. In British English, we generally only open conversations with strangers using set topics: shared adversity on public transportation, the weather, complaints about waiting or asking for something. When we open a conversation with someone we know, we tend to use general questions such as “How was your holiday?” or “ How’s it going?”