Initial Environmental Scan November 2008

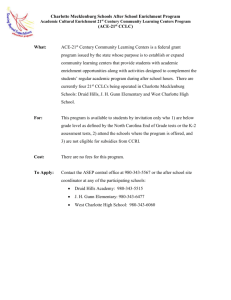

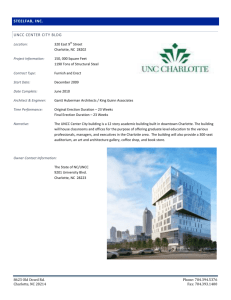

advertisement