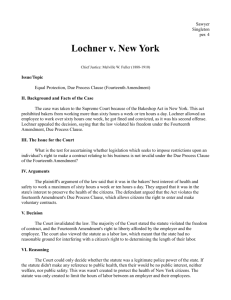

Constitutional Law II Outline

advertisement