Rob Famigletti

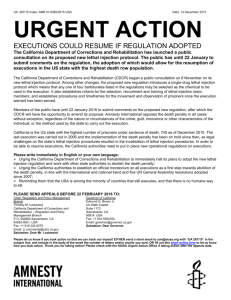

advertisement