FINDING A WELL-DEFINED PARADIGM FOR WELL

advertisement

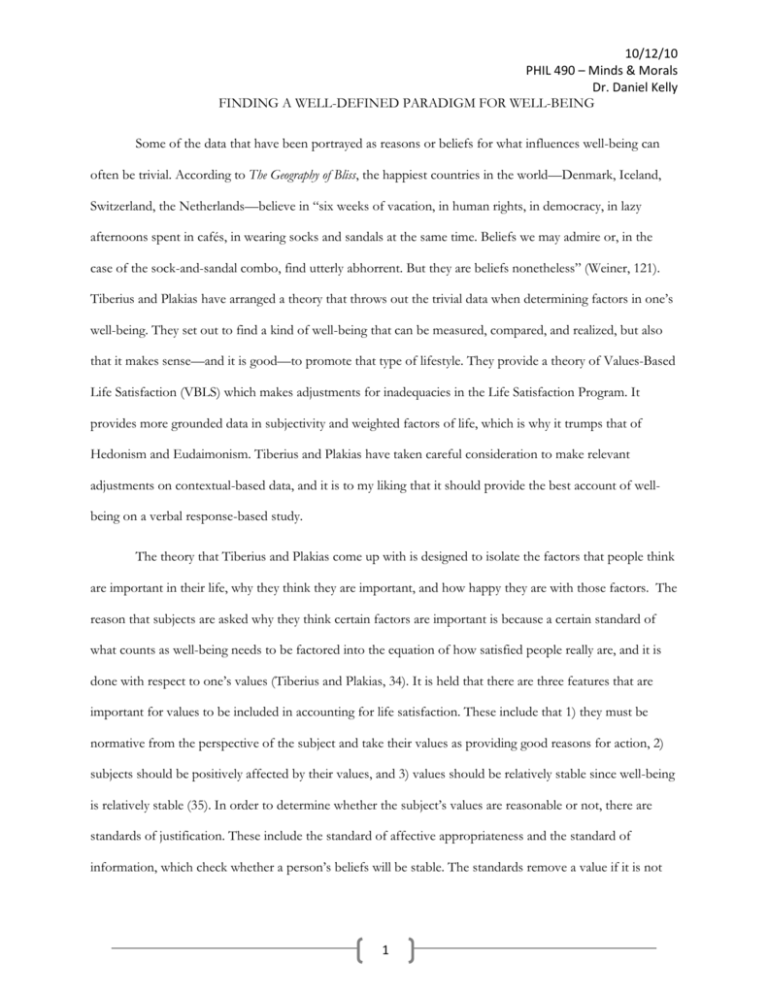

10/12/10 PHIL 490 – Minds & Morals Dr. Daniel Kelly FINDING A WELL-DEFINED PARADIGM FOR WELL-BEING Some of the data that have been portrayed as reasons or beliefs for what influences well-being can often be trivial. According to The Geography of Bliss, the happiest countries in the world—Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland, the Netherlands—believe in “six weeks of vacation, in human rights, in democracy, in lazy afternoons spent in cafés, in wearing socks and sandals at the same time. Beliefs we may admire or, in the case of the sock-and-sandal combo, find utterly abhorrent. But they are beliefs nonetheless” (Weiner, 121). Tiberius and Plakias have arranged a theory that throws out the trivial data when determining factors in one’s well-being. They set out to find a kind of well-being that can be measured, compared, and realized, but also that it makes sense—and it is good—to promote that type of lifestyle. They provide a theory of Values-Based Life Satisfaction (VBLS) which makes adjustments for inadequacies in the Life Satisfaction Program. It provides more grounded data in subjectivity and weighted factors of life, which is why it trumps that of Hedonism and Eudaimonism. Tiberius and Plakias have taken careful consideration to make relevant adjustments on contextual-based data, and it is to my liking that it should provide the best account of wellbeing on a verbal response-based study. The theory that Tiberius and Plakias come up with is designed to isolate the factors that people think are important in their life, why they think they are important, and how happy they are with those factors. The reason that subjects are asked why they think certain factors are important is because a certain standard of what counts as well-being needs to be factored into the equation of how satisfied people really are, and it is done with respect to one’s values (Tiberius and Plakias, 34). It is held that there are three features that are important for values to be included in accounting for life satisfaction. These include that 1) they must be normative from the perspective of the subject and take their values as providing good reasons for action, 2) subjects should be positively affected by their values, and 3) values should be relatively stable since well-being is relatively stable (35). In order to determine whether the subject’s values are reasonable or not, there are standards of justification. These include the standard of affective appropriateness and the standard of information, which check whether a person’s beliefs will be stable. The standards remove a value if it is not 1 tested as normative, and thus remove the score in life satisfaction for that question. If the value passes and is seen as normative, the satisfaction score is kept and used in tabulating the results. There are two ‘tests’ to see if the score should remain useful, one if the values of the subject match the life satisfaction score, and two, if the values are justified by the standards set for justification. The way a score can be ‘defeated’ is that life satisfaction is “not based on one’s values at all” or if “the values that it is based on do not meet the standards for values, that is, if they are ill-informed or ill-suited to the person’s affective nature” (37). The answers that remain are part of one’s value-based life satisfaction, which is the full assessment of well-being. Life Satisfaction Score Justified values (meet standards) Used in Values-Based Life Satisfaction score Values of Subject Values Differ From Life Satisfaction Values Match Life Satisfaction Criteria Unjustified values Not used in ValuesBased Life Satisfaction score Figure 1 The Values-Based Life Satisfaction system that is developed measures one’s overall condition of life based on the standards of one’s own values. The only way a subject’s self-reported condition is disregarded is if the subject is influenced by a source he doesn’t care about, he is misinformed, or what he says fits poorly with her affective nature (43). An example that a subject could be influenced by would be a disabled person in the room during the life satisfaction questionnaire. In studies that have been done using this scenario, subjects “tend to evaluate their lives as going better when there is a disabled person in the room than they do when the disabled person is not there, presumably because the disabled person changes the evaluative standard that the people use in their judgment” (27). Say, for example, a man has a high Life Satisfaction score pertaining to marriage. In his self-reported values, family is one of his values. This score then passes the first test. If in his reasoning why he highly values family, his answer involves acceptance in his church or 2 approval of his parents, the reasoning of the values would not be justified because her values are not normative. The VBLS is superior to Hedonism for various reasons. VBLS, unlike Hedonism, includes life satisfaction reports which can “distinguish qualitative differences between pleasurable experiences and count them differentially as part of a person’s well-being” (16). Subjects may find that certain aspects in one’s life are more important in determining how their life is going, and those aspects will have more value placed on them. Hedonism has a collective measurement on how much pleasure and how little pain a subject has experienced, but doesn’t have a way of weighting the pleasures that valued by the subject, thus contributing more to their overall well-being. Hedonism depends on how well correlated the subject’s pleasure and pain are with his belief about his well-being, which are speculative measures that are not reliable (Stich, Doris & Roedder, 24). Hedonism also does not have a fail-safe that removes any pleasure or pain that the subject does not value or values for the wrong reasons from their measurement of well-being. In fact, “Hedonism arbitrarily privileges a particular subjective experience (pleasure) without regard to how important this experience is from the subject’s own point of view” (33). Eudaimonism is inferior to the VBLS account because VBLS “does not build in arbitrary external norms about what must be achieved for a life to go well: it is the subjects own norms that count” (Tiberius and Plakias, 16, italics in original). In VBLS, there are no universal norms for what constitutes well-being; it is driven by what drives the subject. Eudaimonism does “not locate well-being in subjective experience at all, thus creating a gap in the theory’s recommendations and people’s motivations” (33). VBLS is superior to Eudaimonism because it can be more accurate at picking out the norms that matter on a subject to subject basis. Eudaimonism also does not have a fail-safe to remove any factor of the assessment that the subject does not value or values for the wrong reasons. It is important in the assessment of well-being to eliminate irrelevant data, and the removal of non-normative reasons for particular assessments does just that. The Value-Based Life Satisfaction is based on Tiberius and Plakias understanding that reasons for well-being should be based on a “normative authority” that will give people reason to follow the theory. 3 These are specifically reasons that are motivating and justifying, and therefore they purport that the two desiderta that any viable theory of well-being should meet include “(1) that people (everyone to whom the theory is supposed to apply) will have some motivation to care about what the theory recommends and (2) that there are standards of justification (correctness and appropriateness) for these recommendations” (32). The type of theory that is most appropriate to meet these criteria is that of life satisfaction. The point of finding normative reasons for life satisfaction is to remove the judgments that people make that are highly context-dependent. This is due to the fact that “judgments of overall life satisfaction and life satisfaction attitudes are shaped by the information that is accessible to us at the time of making the judgment and by other factors such as mood” or even the weather (25). To reiterate, “selective attention heavily influences a person’s subjective point of view, and what people happen to attend to seems arbitrary in a way that other things do not,” so it is best to remove the select arbitrary influences in judgment (31). Since judgments can be easily swindled by ones environment, it is important to throw out the unstable, temporary data that plays no normative role in the assessment of well-being. The VBLS account satisfies the two desiderata that should be included in well-being because it does not matter what arbitrary factors are in subjects’ assessments because only the judgments that matter on a normative basis will count towards their scores. The normative basis—as it has been said—is in an individual’s values that are justified by the two standards of correctness and appropriateness. In this manner, only a select amount of judgments will be recorded in a subject’s life satisfaction assessment. The removal of unfair data—including that of a subject that is misinformed or is not positively affected by his response— brings about a clearer understanding of what factors are truly playing a role in a person’s well-being. People are going to be feel a sense of well-being when what they care about—for the right reasons—is going well for them in their lives. Different criteria occupy goals in people’s lives, thus their well-being is going to be affected by different criteria—the premise of the first desideratum. Only criteria that truly affect the person and that the person is accurately informed about will be taken into account as a factor in their assessment— the premise of the second desideratum. These desiderata have the flexibility to be applied to a complete range 4 of individuals, from various backgrounds and outlooks on life. These desiderata idealize the responses of the subjects to standardize their affect on the subject. Objectors may suggest that there is a possibility of a gap between subjective experience and wellbeing created by the idealization of the responses. Since there are so many responses that are eliminated because their failure to meet the various standards, one might be skeptical of the right degree of idealization in the model. For this reason, some might believe that the way Tiberius and Plakias have altered the life satisfaction accounts may make them insufficiently grounded (42). They respond by saying they do not believe so, and it is only an extension of the standard life satisfaction test, which asks people to make judgments on important domains to them. It is very similar to what has been taking place in other life satisfaction theories, it just has an adjusting factor for a person’s different values and why they hold those values. The VBLS only takes out the judgments that are cared about for the wrong reasons. VBLS provides good reason for using non-self-report measures because self-reports are “imperfect indicators” on how well a subject is doing according to his own values. They suggest including measures that are likely to meet the standards test—like “friendship, family relationships, health, and good work”—to their method to account for the imperfect indicators (43). Another objection might be that cognitive science may trump the imperfect methods of questionnaires. Although this may be true, Tiberius and Plakias would stay that that type of methodology is currently unattainable. When asked the same questions while having their brain scanned, it is not certain that the activities in the brain would correspond to positive factors of well-being as opposed to negative ones. The degree of accuracy to questions can also not be measured on a lie-detector test as the results of them are often not correlated with truth. In the current measurement of well-being, it is best to just modify the current system to more accurately depict the factors that influence it. This is the reason for tweaking the life satisfaction accounts with relevant value-based information from each subject. It can narrow down the correlation of what factors contribute to well-being. Until a breakthrough in cognitive science arrives, it is 5 best to not try revolutionary but less accurate tests to that which has become more effective at measuring well-being. Tiberius and Plakias currently have the best methodology for measuring well-being because it is not based on universal norms, but the norms change based on the subject so it in theory can be used universally. Hedonism and Eudaimonism often leave out aspects of or include aspects in an assessment which may be important or not important, respectively. The Values-Based Life Satisfaction account “provides an explanation of the normative importance of well-being without sacrificing the relationship to subjective experience” (44). These normative, value-based judgments are beneficial to assessment because they are an accurate portrayal of what factors justifiably influence a person’s well-being. It is better to have norms that are relative to the subject than generalized norms because “only a fool or a philosopher would make sweeping generalizations about the nature of happiness. I am no philosopher, so here goes: Money matters, but less than we think and not in the way that we think. Family is important. So are friends. Envy is toxic. So is excessive thinking. Beaches are optional. Trust is not. Neither is gratitude” (Weiner, 322). Although there have been assessments of what is beneficial to one’s well-being, the answers, like those in The Geography of Bliss, may not be justified in their value. Weiner, Eric. The Geography of Bliss. (2008). New York: Hachette Book Group . Stich, Stephen; Doris, John M. & Roedder, Erica. “Altruism.” The Handbook of Moral Psychology. (2008). New York: Oxford University Press. Tuberius, Valerie & Plakias, Alexandra. “Well-Being.” Anthology of Moral Psychology. (2008). New York: Oxford University Press. 6