Life as a US Senator Overview

advertisement

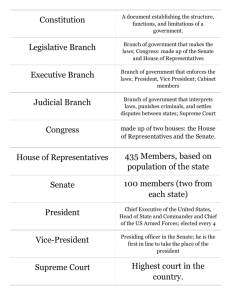

Life as a U.S. Senator Overview Life as a U.S. Senator Formal Senate powers are articulated in Article I (legislative power) and Article II (“advise and consent”) of the U.S. Constitution. In fulfilling these responsibilities, Senators serve on committees and subcommittees, attend hearings, cast votes, meet with constituents, craft legislation, attend legislative briefings and speak at various functions. Many of these responsibilities are not unique to the Senate as member of the House of Representatives perform many of the same functions. House and Senate Differences One obvious difference between Senators and Representatives is their qualifications for office. Senators must be at least 30 years old, reside in the state that they represent, and have been a U.S. citizen for at least nine years. Representatives must meet the same residency requirement, must be at least 25 years old, and a U.S. citizen for at least seven years. Senate terms are longer (six years) compared with House terms (two years). Statewide Senate races tend to be more expensive than district-based House races. Seven states are represented by a single person serving as an at-large Representative. Senators provide “advice and consent” on presidential nominees for U.S. Supreme Court judgeships and Cabinet Secretary positions. However, since all revenue bills must originate in the House, Senators may not introduce bills that raise revenue, although the Senate may make changes to and reject such bills. Moreover, Representatives decide whether or not to initiate the impeachment process against federal officials, whereas Senators vote hold the trial on those impeachments that meet the necessary majority vote in the House. Changes in Congress in the Recent Past Within the context of these Constitutional differences, both houses of Congress have experienced institutional and external changes in past decades that have altered the legislative process, Congressional relations with the President and the Executive Branch, and relations with the public, the media, interest groups and political parties. Party polarization has become increasingly more visible in both chambers since the 1960s, but has become much more pronounced since the mid-1990s. Polarization has led to legislative gridlock on many policy issues, as compromise has taken a back seat to pursuing party agendas. In an attempt to curb the considerable power committee chairs had in the pre1970s Congress, procedural reforms were enacted that gave party caucuses greater power to select committee chairs. Before these procedural reforms, seniority played a much more important role in committee chair selection than it does now. The number of subcommittees has also increased, which better distributes power. In 1975, the Senate voted to amend its own rules to reduce the number of votes necessary to invoke, which is now more often used by the minority party to impede legislation. The results of these and other reforms since the 1970s have resulted in party leadership becoming increasingly successful in pressuring Congress members to promote their party’s agenda with donations raised by Congressional campaign committees and leadership committees. These funds are used to reward loyal party members while punishing those who lack party discipline. Put differently, reforms intended to expedite the legislative process and better balance the distribution of power, have instead empowered the leadership among the Republican and Democratic parties and reduced the number of “centrist” members in both parties. Another factor affecting relations in Congress has been advances in media technology. The House and Senate now allow cameras into the House and Senate chambers. CSPAN and CNN ushered in a new era of cable news that made broadcasting news possible at any time. Critics claim that the increased competition among cable news agencies vying to be the first to report on major stories has led to a decrease in the reliability of the news. Moreover, the increase in the number and types of cable news options led to increased calls to repeal the Fairness Doctrine. The Fairness Doctrine was enacted in 1949 and enforced by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The doctrine requires those holding broadcast licenses to present controversial issues of public importance in a fair and balanced fashion. Broadcasters complained that this requirement violated the First Amendment right to free speech. In 1969, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the Fairness Doctrine in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367. However, due to mounting pressure from the President and some Congress members, the FCC decided to reevaluate the Fairness Doctrine and determined, in 1987, that the increased competition resulting from mass media made the Fairness Doctrine unnecessary. The FCC also determined that the Fairness Doctrine actually led broadcasters to cover controversial issues less rather than spending the time and money necessary to provide balanced coverage. Calls to revive the Fairness Doctrine have continued in Congress ever since, but in 2011, the FCC formally removed the language that implemented the Fairness Doctrine. Many believe that the termination of the Fairness Doctrine is directly related to the growth of political talk radio in the 1990s, increasing bias among cable news providers, and the accelerated decline of civility in politics. Formal Senate roles have remained the same as when the Senate was created in 1787. However, the founding fathers could not have anticipated the level of access to Congress’ daily operations the public enjoy as a result of new forms of technology employed by the media. Many positive consequences of unprecedented access have fallen by the wayside as the negativity and partisan quarreling that plays out in political news from the radio to cable television carries over to Congress itself. Instead of new technology enabling the public to gain insight into complicated legislative politics, the media contribute to inciting partisan bickering that hampers the legislative process.