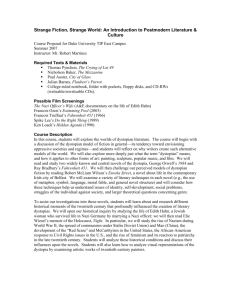

Defining the Genre: Utopia and Dystopia

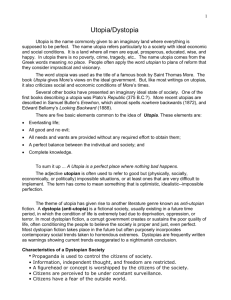

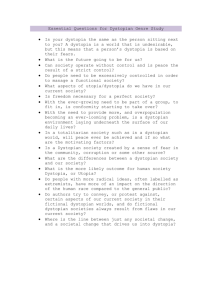

advertisement

Defining the Genre: Utopia and Dystopia Posted by Kelly Melcher People have been dreaming of the perfect society since long before Sir Thomas More wrote his book Utopia in 1516. Over the centuries and still today people wonder, speculate, and try to create the perfect society, although in some cases this leads more towards calamity than utopia. Both utopia and its antithetical counterpart dystopia have long be themes in literature and have been the subject of many a science fiction story. Based on name alone, these two subjects seem as though they are completely different, but as we explore what they mean and how they fit in with the science fiction genre we will explore their similarities as well as their differences. When we discuss utopia, instant images come to mind: Blue sky, people lazily lounging around, not a care in the world, off somewhere a bird is singing and life is grand. The word “utopia”, which was created by Sir Thomas More to be the name of his fictional island, is derived from two Greek words. The first is “Outopia” meaning “no place” and the second is “Eutopia” meaning “good place”. The name itself seems to imply the futility of such a place, or such an existence, but that hasn’t stopped men and women, writers and rulers alike from dreaming of such an arrangement. The word “utopia” has come to mean a perfect but unreachable society, something that we strive for but can never quite attain. What separates writings on and about Utopian societies and a political or philosophical debate? Most works which describe a Utopian setting are written with a lack of regard or notice to whether or not removing the evils of societies is even possible. It is written as a fictional account, of either discovering or being described by another, but not how it is actually possible to attain such a society (Mastin). Science fiction perhaps more than any other genre in fiction explores, if you’ll excuse me, places where “no man has gone before”. Constraints of reality and what is really possibly versus what could be, what might be, and any other possible scenario imaginable can be explored through science fiction. Utopia is less the perfect political system and more stepping away from society and civilizations. It calls for the creation of practical and necessary improvements. Why upgrade the infrastructure when you could spend your time improving the plumbing so that everyone has water? However, this is a practice best practiced in fiction. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century many communities based on the Utopian philosophy were founded, and most of them failed. The Utopian ideal fails when it is enforced by politics. The development of utopia in fiction has lead to dystopia. When utopia isn’t relevant what do you have left? In our current society the rich have no urgency for the perfect lazy carefree life, and for the destitute, there seems no way out of a life of violence and poverty. People become both complacent and jaded towards the lofty aspirations of utopia. Others so desperate for that utopia try to enforce it with an iron fist. This is the genesis of dystopia (Jacoby, 1-6). In Ayn Rand’s Anthem, the main character Equality 7-2521is assigned to be a street sweeper because he transgressed against the natural order by being inquisitive when he hadn’t been assigned to be a Scholar. Children are raised en masse, jobs are assigned, and supposedly everyone is equal (Rand). Anthem is not the only example in dystopian fiction of this forced utopia, nor was it the first or will it be the last. In Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, every action performed by a person is prescribed by “The Table”, everyone wears the same uniform, and surgery is even performed in some cases to change physical features to more closely resemble those of the rest of the population (Zamyatin). If Utopia is ultimate contentment, then dystopian fiction is necessarily told from a malcontent point of view. The narrator is often speaking as a member of the society, originally content with their position until an epiphany causes them to realize that everything isn’t perfect. In Anthem Equality 7-2521 rediscovers electricity and furthermore the light bulb, however rather than being heralded as a bright new mind he is chastised for attempting to ruin the equilibrium of society. His epiphany comes when they try to destroy what he has created, and suddenly he realizes that the society isn’t perfect and ideal but repressive and unequal (Rand). D-503 the main character of We meets the enigmatic I-330 who exposes him to new ideals and causes an inner conflict between his past ideals and the new dreams and thoughts bubbling up in him because of what she has exposed him to (Zamyatin). Utopian and Dystopian fiction seem very different, but there are some similarities. Both exhibit extremes, one overly hopeful, the other overly ominous. Utopians are the dreamers for what might be, while dsytopian fiction is more of a nightmare, and it is a less whimsical idea of what might be. Both societies aspire for absolute equality and for a better tomorrow, even if their approaches are completely different. There could not be dystopia without desire of a utopia. After all, the society in We was structured to make everyone content, and the goal was a perfect society. There could not be utopia if not for fear for the overbearing nature of dystopia. These two ideals have been thought about and discussed for centuries, perhaps even as long as there have been civilizations. Science fiction is the playground for wouldbe philosophers to explore the political possibilities that may not have any real world application, or may not even be practicable in reality. As long as there is a political system there will be people who will want to see it changed and who will want revolution or evolution. In these conditions, the emotions and thoughts that drive the Utopian belief or the Dystopian outcome will continue. Utopian Fiction: Utopia by Sir Thomas More Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin Men Like Gods by H.G. Wells Ecotopia : the notebooks and reports of William Weston by Ernest Callenbach Old New Land (Altneuland) by Theodor Herzl Unveiling a Parallel: A Romance by Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant Herland and Selected Stories by Charlotte Perkins Gilman Macrolife: A Mobile Utopia by George Zebrowski The Probability Broach by L. Neil Smith White Mars by Brian Aldiss Dystopian Fiction: Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand The Bar Code Tattoo by Suzanne Weyn Brave New World by Aldous Huxley The Sheep Look Up by John Brunner The Postman by David Brin Memoirs Found in a Bathtub by Stanislaw Lem Jennifer Government by Max Barry Elvissey by Jack Womack Uglies (Boxed Set) by Scott Westerfield Rant: The Oral Biography of Buster Casey by Chuck Palahniuk Resources: Jacoby, Russell. Picture Imperfect : Utopian Thought for an Anti-Utopian Age. New York: University of Tokyo P, 2005. Mastin, Luke. “Development of Utopian Literature.” Utopian Literature. 13 Dec. 2008 http://www.lukemastin.com/utopia/development.html. Rand, Ayn. Anthem. New York: Tarcher, 2000. Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. Trans. Clarence Brown. New York: Penguin Classics, 1993. http://fandomania.com/defining-the-genre-utopia-and-dystopia/ Dystopian Fiction East and West Erika Gottlieb Table of Contents and Introduction Introduction Acknowledgments PART ONE: DYSTOPIA WEST 1 What Is Justice? The Answers of Utopia, Tragedy, and Dystopia 2 Nineteenth-Century Precursors of the Dystopian Vision 3 The Dictator behind the Mask: Zamiatin?s We, Huxley?s Brave New World, and Orwell?s Nineteenth Eighty-four 4 Dictatorship without a Mask: Bradbury?s Fahrenheit, Vonnegut?s Player Piano, and Atwood?s The Handmaid?s Tale PART TWO: DYSTOPIA EAST The Soviet Union 1920s?1950s 5 The Writer on Trial: Socialist Realism and the Exile of Speculative Fiction 6 The Dystopia of Revolutionary Justice: Serge?s Conquered City, Zazubrin?s ?The Chip,? and Rodionov?s Chocolate 7 The Legalization of Terror: Platonov?s The Foundation Pit, Ribakov?s Children of the Arbat, and Koestler?s Darkness at Noon 8 Terror in War, Terror in Peace: Grossman?s Life and Fate, Tertz Sinyavski?s The Trial Begins, and Daniel?s This Is Moscow Speaking PART THREE DYSTOPIA EAST The Soviet Bloc 1950s?1980s 9 Collective Paranoia: The Persecutor and the Persecuted: Andzrejewski, D?ry, Fuks, Hlasko, ?rk?ny, Vaculik, and Mrozek 10 Kafka?s Ghost: The Trial as Theatre: Klima?s The Castle, Karvas?s The Big Wig, and Havel?s Memorandum 11 From Terror to Entropy: The Downward Spiral: Konwicki?s A Minor Apocalypse, D?ry?s Mr G.A. in X, and Zinoviev?s The Radiant Future 12 Speculative Fiction Returns from Exile: Dystopian Vision with a Sneer: Voinovich?s Moscow 2042, Aksyonov?s The Island of Crimea, Dalos?s 1985, and Moldova?s Hitler in Hungary 13 Dystopia East and West: Conclusion Notes Bibliography Index Introduction Dystopian fiction is a post-Christian genre. If the central drama of the age of faith was the conflict between salvation and damnation by deity, in our secular modern age this drama has been transposed to a conflict between humanity's salvation or damnation by society in the historical arena. In the modern scenario salvation is represented as a just society governed by worthy representatives chosen by an enlightened people; damnation, by an unjust society, a degraded mob ruled by a power-crazed elite. Works dealing with the former describe the heaven or earthly paradise of utopia; those dealing with the latter portray the dictatorship of a hell on earth, the "worst of all possible worlds" of dystopia. Even a casual reading of such classics of dystopian fiction as Zamiatin's We, Huxley's Brave New World, or Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-four will make it obvious that underlying this secular genre the concepts of heaven and hell are still clearly discernible. In fact, the post-Enlightenment author's vision of a collective hell for society is not that far removed from Dante's medieval dream-vision of Dis, the city of hell. As for the function of hell in the overall framework of The Divine Comedy, we should remember that the purpose of the narrator-protagonist's entire journey in hell is to serve him - and his readers - as a warning to avoid the sin that condemns the sinner to eternal damnation, and to pursue instead the ways up to heaven: Beatrice, who watches over Dante from above, sends to him Virgil, the voice of reason, to lead him out of the Forest of Error - the pain and confusion caused by his sinful state. Under Virgil's guidance the narratorprotagonist has the unparallelled privilege of travelling through the nine circles of hell unscathed in order to witness the endless suffering of all those who died as sinners. Beatrice makes Dante confront these horrors in order to warn him about the possible consequences of his own erring ways and thereby to encourage him not to end up in hell. The strategies of Zamiatin, Huxley, and Orwell are also significantly the strategies of warning. As readers we are made to contemplate Zamiatin's One State, Huxley's World State, and Orwell's Oceania, each a hellscape from which the inhabitants can no longer return, so that we realize what the flaws of our own society may lead to for the next generations unless we try to eradicate these flaws today. The correspondence between religious and secular concepts in dystopian fiction is still so strongly felt that, if we examine Nineteen Eighty-four closely as the prototype of the genre, twentieth-century dystopian fiction reveals the underlying structure of a morality play. Orwell's protagonist, a modern Everyman, struggles for his soul against a Bad Angel; he struggles for the dignity of the Spirit of Man against the dehumanizing forces of totalitarian dictatorship. The parallel could be carried further. While the medieval morality play implies that the fate of the human soul will be decided at the Last Judgement, the modern dystopian narrative puts the protagonist on an ultimate trial where his fate will be decided in confrontation with the Bad Angel in his secular incarnation as the Grand Inquisitor, high priest of the state religion and God-like ruler of totalitarian dictatorship. Given the injustice endemic to the "bad place," this decision will invariably be in the negative: in Zamiatin's We, D-503 is sentenced to lobotomy; John Savage in Brave New World to madness brought on by loneliness and ostracism; Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-four to a transformation of the individual personality until it embraces all it abhors, a state worse than the effects of lobotomy. The sinister and irrevocable transformation of the protagonist represents the irrevocable damnation of his society. It is one of the most conspicuous features of the warning in these classics of dsytopian fiction that once we allow the totalitarian state to come to power, there will be no way back. As for the origin of the term "dystopia," we find it of comparatively recent coinage. In his 1946 preface to Brave New World Huxley still refers to the bad place as a utopia, using the term he felt stood for any speculative structure taking us to the future. It was only in 1952 that J.Max Patrick 1 recommended the distinction between the good place as "eutopia" and its opposite, the bad place, as "dystopia." In discussing a selection of Russian novels written since Stalin's death and critical of the Soviet regime's allegedly utopian purpose, Edith Clowes borrows Gary Morson's term of "meta-utopia" - that is, a work that is "positioned on the borders of the utopian tradition and yet mediates between a variety of utopian modes." To distinguish these books from what she sees as the far more limited scope of dystopian fiction, she argues that meta-utopia represents a "much greater challenge to current readers ? than dystopian novels do" because it "refers to a social consciousness involving social and cultural pluralism." By contrast, according to Clowes, dystopian novels advocate a "nostalgic revision of the past age" and "deconstruct utopian schemes, only to abandon the notion of a beneficial social imagination," thereby embodying a "nihilistic attitude toward both the present and the future, closing both off to a new imaginative possibility."2 But is her definition of dystopia valid if we examine it in the light of such classic examples of dystopian novels as Zamiatin's We, Huxley's Brave New World, and Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-four? And is the meta-utopia of Tertz's The Trial Begins or Daniel's This is Moscow Speaking, included among Clowes's examples, indeed all that different from the intentions, attitudes, and narrative strategies of these three classics of dystopian satire? This study will answer both questions in the negative. As for a thematically more neutral definition of this "bad place," Lyman Sargent suggests that we look at dystopia as a social structure that is worse than the present social system. If, however, we listen to postmodern criticism, relying on thinkers like Foucault, for example, any society functioning at the present time (or possibly at any other time as well) could be regarded as such a "bad place." Although I believe that the postmodern critic's overly broad use of the notion of dystopia is counterproductive to a clear definition of what is unique about dystopian thought or dystopian fiction, I also believe that Professor Sargent's definition of dystopia as a system worse than our own probably does not cover all works with a dystopian impetus. In fact, if we take a look at works of political criticism produced in Eastern and Central Europe commenting on the injustice rampant in the writer's own society during periods of dictatorship and terror, these works are still clearly expressive of the dystopian impulse, although they deal with the writer's own society "as is." In other words, there are historical phenomena that create societies that should be described as dystopic, societies where the literary imagination refuses to envisage a world worse than the existing world of reality. Therefore, before we are to arrive at a comprehensive delineation of the salient characteristics of dystopian fiction as a genre, maybe we should also define the characteristics of a society that is dystopic. It has been said by Hungarian essayist B?la Hamvas that the modern age has been spent "under the aegis of the tension between Messianism and dictatorship." Throughout the nineteenth century the world awaited a secular Messiah to redress the ills created by the Industrial Revolution in a double incarnation: first as science, which was to create the means to end all poverty, and second as socialism, which was to end all injustice. By eagerly awaiting the fulfilment of these promises, the twentieth century allowed the rise of a false Messiah: state dictatorship. It may not be unfair to speculate that the oscillation between the mask of the Messiah and the cruel face of an all-powerful Dictator behind the mask is what delineates the parameters of dystopian thought and creates the suspense in dystopian fiction of the protagonist's nightmare journey to "unmask" the secrets held by the "High Priest" of the political system. In Zamiatin's We, Huxley's Brave New World, and Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-four this nightmare journey ends invariably in the protagonist's trial, followed by retribution tantamount to his destruction or, even more horrifying, to his sinister transformation. In the context of the Soviet experiment of building socialism, Koestler and Orwell were certainly not the first, although they were among the best-known thinkers in the 1940s who decided to show the real face of dictatorship behind the Messianic mask. This effort at "unmasking" was not well received by their confr?res, the leftist intellectuals in the West, whose virtually religious infatuation with the Soviet Union as the only country in the world that was building socialism started at the time of the 1917 revolution. For some this infatuation was sustained through Stalin's show trials in the 1930s and into the early 1950s; for many, probably right up to the violent overthrow of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and for still others right up to the crushing of the Prague Spring by Soviet tanks in 1968. At these various junctures in history the leftist intelligentsia in the West was confronted with the disheartening fact that the Messianic promise of the age-old utopian dream of socialism as a cure for the clearly obvious pathologies of capitalism had merely led to new pathologies in the form of the virulent psychoses of totalitarian dictatorship. What should these new pathologies be attributed to? Stalin's pathological personality? To the fact that the young Soviet Union had to struggle with potentially overwhelming external enemies? Or to the historical irony that made the Bolsheviks successors of an autocratic regime that had created a tempting precedent? Perhaps to the fact that Stalin's revolution (or counterrevolution) in 1929 gave rise to a ruthlessly self-serving new bureaucracy - a new ruling class? These are not the questions to ponder at this point. Maybe one is left frustrated discussing the flaws of socialism because, as Chesterton said of Christianity, it is something that has never been tried yet. Thus, in the case of Stalin's regime, one could argue that the slogans ostensibly drawing on Marx's theories of socialism were nothing but a camouflage for Russian nationalism and imperialism, or simply for Stalin's and his self-serving elite's thirst for power. Other historians and political analysts, of course, concentrate on elements in Marxist theory that they see as conducive to the development and legitimization of a totalitarian regime. Some ponder whether we should not relate the terror and coercion of Stalinism to the intellectual coercion implied by Marx's notion of historical determinism. Others raise the question whether the Party's oppression of all opponents and its disregard for the universal principles of human justice are not the consequences of Marx's failure to provide a sufficient model for a political process of persuasion and for a juridical system based on respect for human rights. Marx did make the assumption that once the proletariat came to power and established socialism, the very notion of political and legal mechanisms that had been necessary to resolve conflicts created by the economic injustice inherent in a class society would become superfluous. Be that as it may, in the field of history the shocking reversal between high utopian expectations and deep disillusionment with the Soviet attempt at socialism has been central to the nervous vacillation of the utopian-dystopian axis of our times, demonstrable not only in the more abstract realm of political thought but also in the internal and external politics of individual nations or entire power blocs. In the realm of literature it has been a task worthy of the greatest of political satirists to comment on this reversal as having revealed the cruelty of dictatorship under the false Messiah's mask of hypocrisy, and to exhort the reader to see beyond the mask. At the same time it has also been a task awaiting the pen of the tragedian to express the emotional charge of the loss of faith and the disillusionment over what Camus called "the tragedy of our generation ? to have seen a false hope." Dystopias: Definition and Characteristics Utopia: A place, state, or condition that is ideally perfect in respect of politics, laws, customs, and conditions. Dystopia: A futuristic, imagined universe in which oppressive societal control and the illusion of a perfect society are maintained through corporate, bureaucratic, technological, moral, or totalitarian control. Dystopias, through an exaggerated worst-case scenario, make a criticism about a current trend, societal norm, or political system. Characteristics of a Dystopian Society • Propaganda is used to control the citizens of society. • Information, independent thought, and freedom are restricted. • A figurehead or concept is worshipped by the citizens of the society. • Citizens are perceived to be under constant surveillance. • Citizens have a fear of the outside world. • Citizens live in a dehumanized state. • The natural world is banished and distrusted. • Citizens conform to uniform expectations. Individuality and dissent are bad. • The society is an illusion of a perfect utopian world. Types of Dystopian Controls Most dystopian works present a world in which oppressive societal control and the illusion of a perfect society are maintained through one or more of the following types of controls: • Corporate control: One or more large corporations control society through products, advertising, and/or the media. Examples include Minority Report and Running Man. • Bureaucratic control: Society is controlled by a mindless bureaucracy through a tangle of red tape, relentless regulations, and incompetent government officials. Examples in film include Brazil. • Technological control: Society is controlled by technology—through computers, robots, and/or scientific means. Examples include The Matrix, The Terminator, and I, Robot. • Philosophical/religious control: Society is controlled by philosophical or religious ideology often enforced through a dictatorship or theocratic government. The Dystopian Protagonist • often feels trapped and is struggling to escape. • questions the existing social and political systems. • believes or feels that something is terribly wrong with the society in which he or she lives. • helps the audience recognizes the negative aspects of the dystopian world through his or her perspective.