Chapters:

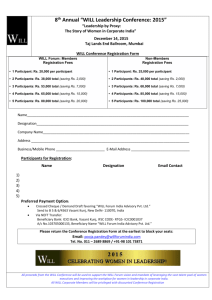

advertisement

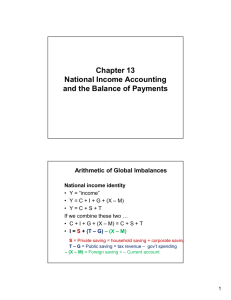

Big Picture Handout #1 (332): The Nuts and Bolts of Macroeconomic Activity It is assumed that all economic activity is composed of exchanges of something for something else, where there are three broad kinds of somethings: goods and services, assets, and factor services. Goods (shorthand for goods and services) are used and exhausted in the act of improving the current period or in the act of creating capital that will improve future periods. Assets are devices by which individuals store wealth over time (e.g., money, stocks – which represents ownership of capital, bonds, real estate, gold…) Factor services are what factors of production (i.e., labor, capital, natural resources) provide. All goods are produced by factors of production, and the amount of goods they produce is equivalent to the amount of factor services they generate. Goods, assets, and factor services are each exchanged for goods, assets, and/or factor services. This exchange perspective even works with regard to government activity: One can think of government goods (and services) provided to the public as being swapped for the taxes (usually in the form of money = an asset) that are collected from the public. The aggregate amount of goods produced by all the factor services is referred to as output and will be considered to take three forms: 1) output that is used and exhausted in the current period by households (= consumption). 2) output that is used and exhausted in the current period by government (which is sometimes called “government consumption” but is more commonly referred to as government purchases). Although one could argue that governments – particularly democracies – are acting with the consent of the households so that this form of output is no different than the first, we will want to isolate how governments impact the macroeconomy and, therefore, we differentiate between the households and government in this regard. 3) output that does not benefit the current period but, instead, is used to create new capital that will benefit future periods. Note that the macroeconomic concept of capital includes knowledge/technology and inventories as well as the usual machines, tools, and other factors of production that are manmade. Output in the form of newly created capital in a period constitutes investment. (Granted, this simple division is imperfect. For one, it implicitly denies that output can both be consumed in the current period and be new capital that influences future periods, as one might expect when purchasing a consumer durable such as a car or refrigerator. Similarly, there is output directed by governments that can also be thought of as public capital or “government investment”, e.g., the construction of a new road. Furthermore, there are measurement problems such as when services are purchased for the development of human capital (e.g., the purchase of education or training services by individuals to make them more productive workers). This may be recorded as consumption (of services) as opposed to investment (in human capital). But macroeconomic thinking strongly differentiates between output appreciated and used up today and output used to produce new capital. We will be able to easily think about output that is part consumption and part investment as well as measurement problems once we firmly establish the fundamental way of thinking about them.) Understanding how output is split between consumption, government purchases, and investment is an important objective of macroeconomics. One reason is that the greater the investment, the greater future output will be, i.e., the greater growth (of output) will be. The 1 first step is to be clear about how a country’s output differs from its income and, then, to differentiate between saving and investment. We define a country’s output (Y)1 as the amount produced within the country’s borders (within a given period). We define a country’s national income (NI)2 as output produced by factors of production that are owned by the country (or, more correctly, the residents of the country) wherever the production occurs in the world (in a given period). Thus, the portion of a country’s output produced using capital owned by a foreigner – i.e., produced from “imported factor services” – is income to the foreign owner. For example, a German who owns a widget factory in the US earns a share of the widget production as compensation for the factor services that his factor of production (i.e., the factory) delivers. In this case, the factor service is exported by Germany and imported by the US.3 This would cause the US’s NI to be less than its Y by the amount of factor payments received by the German in exchange for the imported factor services. In a similar vein, it is possible that an American owns capital in Spain that contributes to Spain’s output. The part of Spanish output that is delivered to the American as compensation for using the capital – i.e., for the factor service exported by the US and imported by Spain – is not Spanish income but, instead, adds to the United States’ NI. If one adds up all the payments the US receives for its exported factor services and subtracts all the payments paid to foreigners for imported factor services, it totals net factor payments (NFP). (Note that this could also be reasonably referred to as “net exports of factor services”, but is not). Accordingly, the relationship between a country’s national income and output is: NI = Y + NFP (1) The income that households and businesses (i.e., the private sector) are free to spend as they see fit does not equal national income because of government involvement. The government collects taxes (T), is responsible for net transfer payments to households (TR) as well as interest payments on the government debt (INT). This means that the private sector’s disposable income (DI) is: DI = Y + NFP – T + TR + INT (2) Note that although all of INT would seem to add to the private sector’s disposable income, it must remembered that those interest payments to foreign holders of domestic government debt would be factor payments to foreigners (and, therefore, what is seemingly added to DI as part of INT is negated by negative contributions to NFP). What is not consumed out of a country’s DI is considered private saving (SPRIV): SPRIV = DI – C = Y + NFP – T + TR + INT – C (3) which finances the period’s acquisition of assets by the private sector. As noted above, an asset is a store of value that transports wealth over time. Forms of capital which are respected as private property are the principal source of assets. Therefore, the creation of new capital (that is considered someone’s property) also constitutes the creation of new assets. The only way for a country to acquire assets without necessarily developing new capital is to purchase an old, existing asset from another country. This would be saving to the person (and country) buying the asset and dissaving by the person (and country) selling it. In this case the world – as a whole – would not experience any saving since the buyer’s saving 1 Most widely used measure of Y: Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Most widely used measure of NI: Gross National Product (GNP). 3 The remaining share of the produced widgets go to pay the other factors of production involved, including the labor provided by the American workers. 2 2 accomplished by obtaining the asset is nullified by the seller’s dissaving that results from relinquishing the asset. It is also important to recognize that the creation of assets does not require the creation of capital. This is because promises of future receipts, i.e., bonds (including promissory notes), constitute assets to those holding them. But the agent issuing and selling a new bond is thought to have taken something that already held value for that agent (i.e., some of her future money balances) and promised them to the purchaser of the bond. So while the issue of a new bond may create a new asset, the fact that the issuer accepts the liability of fulfilling those future promised payments means that net wealth is unaffected since, i.e., those issuing and selling bonds are dissaving which cancels out the saving being accomplished by the individual purchasing the bond. The government also plays a large role in a country’s saving by its government purchases (G) as well as its T, TR, and INT. Government saving (SGOV) is: SGOV = T – G – TR – INT (4) For example, when SGOV<0 the government is running a government (budget) deficit and must find extra financing above what it collects in T to help make its outlays. It does so by issuing and selling government bonds (in the U.S. these are called “Treasuries”). Under these circumstances the government dissaves by the amount of bonds it issues and sells which is, of course, equivalent to the size of the government deficit. A government (budget) surplus is also possible (i.e., SGOV>0) where the government uses the surplus funds to buy back some bonds it has previously issued, which effectively retires the debt. This buying back of its old bonds during the period constitutes government saving during the period. When SGOV = 0 the government has a balanced budget and has no direct effect on the country’s saving. National savings (S) can be perceived from two different perspectives. First, it is the sum of SPRIV and SGOV (i.e., S = SPRIV + SGOV). Of course, when a resident of the country saves by buying a newly issued bond by her government, the increase in SPRIV is just offset by the decrease in SGOV to leave no impact on S. It is also true that – for a given SPRIV – government dissaving will reduce S. Secondly, it also represents the national income that is not allocated to either consumption or government purchases/consumption: S = Y + NFP – C – G (5) which can be corroborated by adding SPRIV and SGOV as defined by Equations (3) and (4). Since the only two things that income can be directed towards is consumption (including government consumption) and the purchase of assets, a country’s S is also the quantity of assets purchased by the residents of that country. A concept that is closely related, but different from that of a country’s S is its investment (I). This “investment” is in the context of a particular country: I is the creation of new capital within the country’s borders during a given period. It is rarely the case that a country’s S – the amount of assets acquired by the country in the period – and its I – the amount of new capital added within its borders in the period – are equal, even though the whole world’s saving must necessarily equal the whole world’s investment. A country with S greater than I is a net purchaser of assets from other countries by the amount (S – I). Alternatively, a smaller S than I makes the country a net seller of assets to other countries by (I – S). Of course, countries that are either net purchasers or net sellers of assets must be exchanging something for the extra assets, and the only possible things they could be exchanging for them are goods, services and/or factor services. 3 Therefore, a country with S >I which is accumulating assets from foreign countries must be exporting more goods, services, and factor services than they are importing in order to compensate the foreign countries for the assets. Similarly, a country with S<I must be importing the corresponding amount of goods, services and/or factor services above what it is exporting. By convention, the term exports (X) refers only to exported goods and does not include exported factor services. Similarly, the word imports (M) refers only to imported goods. The term net exports (NX) simply means X – M. Add the fact that NFP is equivalent to what would be “net exported factor services” (as discussed above), and the following relationship can be stated: S – I = NX + NFP (6) The sum of NX and NFP are defined as the country’s current account (CA), so that Equation (2) can be rewritten: S – I = CA (7) Equation (7) captures a fundamental and famous macroeconomic tenet: A country experiencing a net gain of asset ownership – something commonly (and, maybe confusingly) labeled as “capital outflow” since domestic residents are buying assets outside the country – must be paying for those assets with an equivalent net outflow of goods, services, and factor services. (The opposite also holds: That a net loss of asset ownership – something commonly labeled as “capital inflow” – means the domestic sellers of the assets are being paid with an equivalent net inflow of goods, services, and factor services.) For a different angle on this relationship, consider Equation (7) rewritten as: I = S – CA (8) and then break down S into its component parts (i.e., S = SPRIV + SGOV) so that: I = SPRIV + SGOV – CA (9) This equation clearly reveals the three sources of finance for a country’s investment, i.e., household saving, government saving, and foreigners’ net purchases of domestic assets. Or, one can rewrite the relationship as: I + CA = SPRIV + SGOV (10) where it is easily seen that a negative SGOV that lowers S precipitates a comparable drop in the sum of I and CA. To the extent that I falls, the government deficits are said to crowd out investment. To the extent that CA falls, the dissaving by the government crowds out CA activity (but, unfortunately, it is more common to refer to this as crowding out net exports). One final important macroeconomic relationship to establish is that – during a given period – output is equal to what is consumed, invested, and purchased by the government out of domestically produced output (which is equal to C + I + G – M, since M accounts for those components of C, I, and G that are not produced domestically) plus the domestic output that is exported. Thus: Y=C+I+G+X–M (11) = C + I + G + NX This relationship exhibits the expenditure approach to output, which maintains that output is the sum of goods purchased by the household sector (= C), plus, the goods purchased by the business sector (=I), plus, the goods purchased by the government sector (=G), plus the exported goods sold to foreigners (X), all adjusted by the goods that are imported by households, businesses, and the government as opposed to being produced domestically (M). 4