John E - Parthenon Management Group

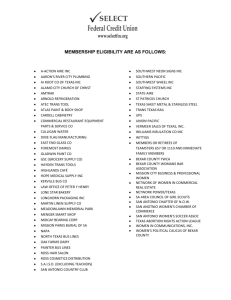

advertisement