Chapter I:

advertisement

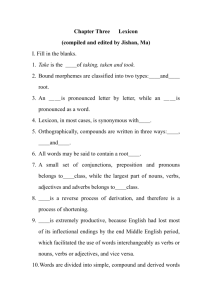

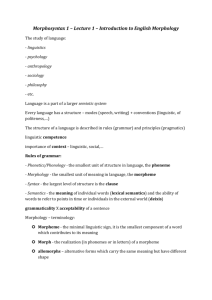

Chapter 2: Words: The Building Blocks of Grammar The previous chapter went to some length to show that the aim of grammar is to label the forms and functions of words, phrases, and clauses. Words are thus the basic building blocks of grammar. From the point of view of grammar, words can be treated as indivisible units, and that is what we will do throughout most of this book. It will nevertheless be useful to us, before taking up grammar directly, to look inside words and learn something about their internal composition. We will see later that, by doing so, we will be better able to define parts of speech and to explain exactly how words pattern in phrases and clauses. MORPHEMES AND WORDS At first glance, it might seem that words are not only the most basic units of grammar but also the most basic units of meaning in language. But it takes little reflection to realize that we can often identify meaningful parts of words. Notice that the following words are all composed of two meaningful parts, the first of which is different in each word and the second of which, spelled s, is the same. It means 'more than one' or 'plural.' 2.1a boys, bags, tails, trains, hams 2.1b tacks, bats, cuffs English therefore has the meaningful word parts boy, bag, tail, train, ham, tack, bat, and cuff, each of which refers to some different thing and each of which, by the way, can stand alone as a whole word. In addition, there is another meaningful word part, s, which, when we attach it to boy, bag, etc., makes us think of more than one boy, bag, etc. We can call any indivisible meaningful word part a morpheme. The term morpheme is based on Ancient Greek, where morph meant 'form' or 'shape.' The term morpheme means 'class of forms or shapes' or 'group of forms or shapes,' i.e., a group of things that together constitute one meaningful word part. But why would we want to call boy or its s ending a 'group'? We do so because one morpheme has the possibility of manifesting itself in two or more (i.e. a group of) spellings or pronunciations. If we add the plural morpheme to the words bush, watch, and judge, we do not spell it s; we spell it es: 2.2 bushes, watches, judges And if we add the plural morpheme to ox, or child, we spell it en: 10 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR 2.3 oxen, children So the plural morpheme is indeed a group of separately spelled letter sequences, s, es, and en. But these three different formal sequences of letters all have the same meaning, 'plural,' and they all appear in the same position, i.e., at the end of nouns, and thus are said to have the same function. The concept of the morpheme always allows the possibility of two or more different forms, such as s, es, and en, even though most morphemes, like boy, have only one form. For a set of different forms (sequences of letters or sounds) to be grouped together as variants of one morpheme, they must have the same meaning and the same function. To show this unity when explicitly analyzing the morpheme sequences in a word, we can invent abstract labels for morphemes, such as -es for the plural morpheme. (The hyphen indicates that this morpheme cannot occur as a word on its own but must be attached to another morpheme on the side where the hyphen appears.) We can now represent the morphological makeup of the previously discussed example words as follows: 2.1a' boy-es, bag-es, tail-es, train-es, ham-es 2.1b' tack-es, bat-es, cuff-es 2.2' bush-es, watch-es, judg-es 2.3' ox-es, child-es Notice that it is not just word endings like the plural morpheme that can vary their form in different words in which they appear. Take a look again at the morpheme sequence child-es in 2.3'. We have already noted that the -es morpheme is spelled en when it is attached to the morpheme child. But we have not until now noted explicitly that the morpheme child also has two spellings; it is spelled child when it occurs alone but childr (with an added r) when the plural morpheme is attached to it. The variant forms of a morpheme are called allomorphs. Thus we can say that the morpheme -es has three allomorphs, spelled s, es, and en, and that the morpheme child has two allomorphs, spelled child and childr. In this discussion, we are focusing on the varied spellings of allomorphs, but notice that there is a similar variation in pronunciation. Take another look at 2.1a and 2.1b, this time reading them aloud and listening to your pronunciation of the final letter: 2.1a boys, bags, tails, trains, hams 2.1b tacks, bats, cuffs 11 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR Even though the plural morpheme has only one written allomorph in all the above words, spelled s, it has two allomorphs in spoken English. Did you notice that, for all of the words in 2.1a you pronounced the plural morpheme with a 'z' sound, but for all of the words in 2.1b you pronounced it with an 's' sound. Some linguists assert that the plural morpheme appears at the end of the words listed in 2.4, 2.5, and 2.6 even though it is neither spelled nor pronounced. In such cases it is said to have a 'zero' allomorph: 2.4 sheep, fish, series 2.5 teeth, geese, feet 2.6 data, criteria, alumni We would thus analyze the morphological composition of the above words as follows: 2.4' sheep-es, fish-es, series-es 2.5' tooth-es, goose-es, foot-es 2.6' datum-es, criterion-es, alumnus-es The alternative to the above analysis would be to claim that English has two words spelled sheep, one having just the meaning, '(a) sheep' and the other having the meaning 'more than one sheep.' Similarly, one would need to assert that tooth and teeth are entirely separate words and that datum and data are separate words. But most people would agree that the plural words listed in 2.4, 2.4, and 2.6 are indeed the same words as their 'singular' counterparts. The analysis proposed in 2.4'-2.6' has the further advantage of treating teeth as an allomorph of the morpheme tooth, an allomorph which is constrained to occur preceding the plural morpheme -es. Here is a summary of what we have learned so far about the plural morpheme: 2.7 Morpheme Label: -es Meaning: 'plural' Function (Position): Occurs at the end of nouns Variant Forms (Allomorphs): The s allomorph as in: (1a) boys, bags, tails, trains, hams (pronounced 'z' in speech) (1b) tacks, bats, cuffs (pronounced 's' in speech) The es allomorph as in: (2) bushes, watches, judges The en allomorph as in: (3) oxen, children 12 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR The 'zero' allomorph as in: (4) sheep, fish, series (5) teeth, geese, feet (6) data, criteria, alumni It is especially common for word endings like the plural morpheme to have more allomorphic variation than morphemes which can themselves be whole words. But some whole-word morphemes can have significant allomorphic variation, especially in speech. Here is a summary like the one for the plural morpheme in 2.7 for one such morpheme: 2.8 Morpheme Label: sign Meaning: 'something that stands for or points to something else' Function (Position): noun (not necessarily attached to any other morpheme) Variant Forms (Allomorphs): The sign allomorph (pronounced 'sayn') as in: sign, assign, consign, cosign The sign allomorph (pronounced 'zayn') as in: design, resign The sign allomorph (pronounced 'sign' -- with 'hard g') as in: signify, signature The sign allomorph (pronounced 'zign' -- with 'hard g') as in: designate, resignation There is a strong tendency in English, despite the complaints that we often hear about English spelling, to be consistent in spelling allomorphs of the same morpheme the same way, even when they are pronounced differently. Thus even though the morpheme sign has four different pronunciations, it is always spelled sign. This makes the English spelling system much more consistent and effective in its primary purpose: to convey meaning visually. Its primary task is not to represent the pronunciation of words (adult speakers of English after all know how to pronounce words) but to communicate ideas. Although morphemes are often defined as 'the basic units of meaning in language,' form and function play an equal role in defining them. Here, as a summary of this section, is an explicit definition of this important linguistic concept: A morpheme, such as the -es morpheme in English, encompasses (a) one or more forms (sound or letter sequences such as s, es, and en) that (b) share the same function, i.e., position in a word (in the case of -es, the final position in a noun), and (c) convey the same meaning (in the case of -es, the idea of 'plural'). MORPHEME TYPES Roots and Affixes The task of morphological analysis is not complete even when all the morphemes are labeled, their meanings and functions specified, and their variant forms (allomorphs) listed. The morphemes which compose a word may be of several types. Consider the word subtract, which is composed of two morphemes, sub- and -tract. Even though their meanings are abstract, they are fairly consistent; sub meaning "down" or "under" and tract "to pull" or "to take." Now, let us see what we can learn about these two morphemes 13 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR by searching for other morphemes that can substitute for each of them in the word subtract. We begin with tract. Here is just a sampling of words with another morpheme substituted for tract after sub-: 2.9a subjoin, sublease, sublet, submerge, subtend 2.9b subject, submerse, submit, subsist, subsume, subvert If we searched in a dictionary, we could surely find dozens, if not hundreds, of other words to add to the above lists. However, even with access to a dictionary, we would find relatively few morphemes that can substitute for sub- before tract. Here is a virtually complete list: 2.10 attract, contract, detract, distract, extract, protract, retract The lists in 2.9 and 2.10 point out an important difference between sub- and tract. If we view the word subtract as composed of two positions (one occupied by sub- and the other by tract), we immediately notice that for each position there are only certain morphemes that can replace the one already there and still make up a genuine word. Very many morphemes can occupy the position of tract but only relatively few can occupy the position of sub-. Furthermore, none of the morphemes that can replace sub- can replace tract and vice versa. This is not an isolated phenomenon true only of the word subtract. Consider the word express, composed of the morpheme ex- and the morpheme press. How many morphemes can you think of that can substitute for press after ex-? Here is a partial list: 2.11a exclaim, exchange, expose, extend 2.11b exalt, excise, exclude, excuse, exempt, exhume, expand, expect, expel, explain, explode, export, expunge, extol, extort, extract, exude Now, how many morphemes can you think of that can substitute for ex- before press? Here is a virtually complete list: 2.12 compress, depress, oppress, repress, suppress Many other examples like these can be cited, examples which show that some morphemes, like tract and press, occupy positions in words where there is a relatively unlimited potential for substituting other morphemes (linguists call such morphemes roots) and that other morphemes, like sub- and ex-, occupy positions where there is a relatively limited potential for substitution (these are called affixes). In our two examples, affixes came before roots. Affixes may also follow roots. Consider the word 14 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR traction, composed of the morpheme tract and the morpheme -ion. It would be easy to show that many morphemes can replace tract in front of -ion (for example, tension, fusion, lesion, version, portion, fission), and thus tract is a root, but that very few morphemes (perhaps only -able and -or) can replace -ion after tract, and thus -ion is an affix. But notice also that, even though we can call sub-, ex-, and -ion affixes, only the first two (sub- and ex-) can precede roots, and only the last one (-ion) can follow roots, which means that we have to sub-divide affixes into two types. Affixes preceding roots are called prefixes, and affixes following roots are called suffixes. But prefixes may also precede other prefixes, as in the word decompression where de- is a prefix that precedes another prefix, com-, and both precede the root press. And suffixes may also follow other suffixes as in the word tractability, where -ity is a suffix that follows another suffix, -abil, and both follow the root tract. Furthermore, a word may have both prefixes and suffixes (for example, distractible, retraction, expressible, compression). Linguists generally cite prefixes with a hyphen after them (for example, sub- and ex-) and suffixes with a hyphen in front of them (-ion and -ible). Let us consider another phenomenon related to the classification of morpheme types. You may have asked yourself earlier why the examples in 2.9 and 2.11 were divided into two groups under a and b. Reexamine these lists of examples, trying to determine what distinguishes 2.9a and 2.11a from 2.9b and 2.11b. They are reprinted here for your convenience: 2.9a subjoin, sublease, sublet, submerge, subtend 2.11a exclaim, exchange, expose, extend 2.9b subject, submerse, submit, subsist, subsume, subvert 2.11b exalt, excise, exclude, excuse, exempt, exhume, expand, expect, expel, explain, explode, export, expunge, extol, extort, extract, exude First, note that the roots in 9a and 11a can function as words without the prefix attached: join, lease, let, merge, tend, claim, change, and pose. Second, notice that all these words are verbs, which suggests that the functional position of the root morpheme following sub- and ex- is that of a verb root. Finally, notice that none of the roots of the words listed in 9b and 11b can function as separate verbs without the prefixes attached: -ject, merse, -mit, -sist, -sume, -vert, -alt, -cise, -clude, etc.. For these reasons, the roots in (9a) and (11a) are called free roots, and those in (9b) and (11b) are called bound roots. Here is a summary of the terms and definitions introduced in this section: 2.13a Roots: morphemes which occupy positions in words where the greatest potential for substitution exists (i) Free: capable of functioning as a word (ii) Bound: incapable of functioning as a word 15 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR 2.13b Affixes (all are bound): morphemes which occupy positions in words where only a limited potential for substitution exists (i) Prefixes: affixes which precede roots and possibly other prefixes (ii) Suffixes: affixes which follow roots and possibly other suffixes Some English Prefixes Examine the sampling of English prefixes in 2.14. The prefixes are grouped into six categories based on their meaning. These meaning categories are not exhaustive, but they do encompass a large number of English prefixes. Two examples of prefixes from each meaning type are given. As you examine the example words listed beside each prefix, notice that when a prefix is added to a root, the composite word is generally the same part of speech as the root without the prefix. Notice also that, while prefixes do not normally have as many allomorphs as did the -es morpheme we considered earlier, there is enough variation to reinforce our definition of a morpheme as an abstract meaning label which may group together a variety of spellings or pronunciations. In this regard, note especially the different pronunciations of poly- in polyglot and polygamy and the different pronunciations of hyper- in hyperactive and hyperbole. 2.14a Number bipoly2.14b Time postpre2.14c Place intersub2.14d Degree hyperultra2.14e Privation un-1 dis2.14f Negation nonun-2 bifocal, bilingual, biceps, bicycle polysyllabic, polyglot, polygamy postwar, postelection, postclassical, postpone prewar, preschool, pre-19th century, premarital international, intercontinental, interact, intermarry subway, subsection, subconscious, sublet, subdivide, subcontract hypercritical, hyperactive, hypersensitive, hyperbole ultraviolet, ultramodern, ultraconservative, ultraliberal, ultramarine undo, untie, unzip, unpack, unleash, unhorse disconnect, disinfect, disown, displease nonconformist, nonsmoker, nonpolitical, nondrip unfair, unwise, unforgettable, unassuming, unexpected PRACTICE 1 (WORKING WITH ENGLISH PREFIXES) All the words listed below begin with a prefix. It is possible to sort them out and create a display very much like the one immediately above in 2.14, containing the same six meaningbased sub-types. Four of the six will have two example prefixes; however, one will have three examples, and one will have only one example. First, sort them out and make the six-part display. Second, identify the root of every example word on your list and determine whether it is bound or free. Here are the words: 16 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR decentralize, decode, semiconscious, discourteous, tricycle, archduke, transfer, de-escalate, archenemy, semifinal, dislike, illogical, disloyal, defrost, amoral, transmit, disobey, semiofficial, monoplane, transplant, protoplasm, tripod, improper, monorail, irrelevant, insane, asexual, foreshadow, supersonic, foretell, monotheism, asymmetrical, superstructure, arch-traitor, prototype, forewarn FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 1 (WORKING WITH ENGLISH PREFIXES) Below is the display called for in Practice 1. Notice how the prefix in- (last line) dramatically changes its spelling and pronunciation to match the initial sound in the base to which it is attached. To provide answers to the second task in Practice 1 (identifying roots as bound or free) I have underlined the letters in each word that realize the root morpheme. Free roots are simply underlined; bound roots are both underlined and in boldface type. It is often very difficult to decide just which letters in a word realize the root morpheme and even more difficult to determine whether that root is bound or free. Only through careful study of the history of a word’s form (its etymology) can such determinations be made. For example, the letters “loy” in the word disloyal in section f below historically descend from the French word loi, which means “law.” One could thus argue that the letters “loy” in disloyal are an allomorph of law and therefore realize a free root. I think that “loy” is not an allomorph of law, and thus the root morpheme represented by those letters is a bound root. There are at least a dozen other similarly problematic words listed below. If you are not sure why I have identified certain letters as the root of a word or why I have indicated it as bound or free, you should examine its etymology in a dictionary a Number monotrib Time foreprotoc Place supertransd Degree archsemie Privation def aNegation disin- monotheism, monoplane, monorail tripod, tricycle foretell, forewarn, foreshadow protoplasm, prototype superstructure, supersonic transplant, transfer, transmit archduke, arch-enemy, arch-traitor semi-final, semi-official, semi-conscious decode, defrost, decentralize, deescalate amoral, asexual, asymmetrical disloyal, discourteous, disobey, dislike insane, illogical, improper, irrelevant Derivational and Inflectional Suffixes Although we focused on prefixes as examples in distinguishing between roots and affixes, we did note that affixes may also be suffixes. In fact, the majority of English affixes are suffixes. Let us now examine the behavior of some English suffixes. 17 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR Consider the verb root pave in the sentences of 2.15. It occurs in (15a) without a suffix and in (15b) and (15c) with suffixes. 2.15a Those workers pave streets for a living. 2.15b The pavement is cracked. 2.15c They paved it only a few years ago. Note that the combination of the verb root pave and the suffix -ment in 2.15b results in a word that is a noun. Other examples of a verb and -ment combining to form a noun are arrangement and astonishment. We may conclude that when the suffix -ment is affixed to a verb, the result is a noun. Now notice that when the verb root pave combines with the suffix -ed in 2.15c the result is still a verb. Thus -ment changes the part of speech of a root to which it is affixed, but -ed does not. Here is another example. The noun root symbol occurs without a suffix in 2.16a but with suffixes in 2.16b and 2.16c: 2.16a Purple is a symbol for royalty. 2.16b White flags symbolize surrender. 2.16c Both the circle and the triangle can be symbols. Note that the combination of the noun root symbol with the suffix -ize in 2.16b results in a verb. Other examples of a noun root and -ize combining to form a verb are hospitalize and vaporize. We may conclude that when the suffix -ize is affixed to a noun, the result is a verb. But notice that when the noun root symbol combines with the suffix -es in 2.16c the resultant word is still a noun. Thus -ize changes the part of speech of a root to which it is affixed, but -es does not. Here is a list of the two roots and four suffixes we have just discussed with summary comments in parentheses: 2.17a pave symbol -ment -ize -ed -es (a verb root) (a noun root) (a suffix that changes verbs to nouns) (a suffix that changes nouns to verbs) (a verb suffix that means "past") (a noun suffix that means "plural") Suffixes like -ment and -ize, which change the part of speech of a word, are called derivational suffixes. Suffixes like -ed and -es, which do not change the part of speech of a word, are called inflectional suffixes. But let us look further into the behavior of these two types of suffixes. 18 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR I noted earlier that a root may have two or more suffixes attached to it. Here are two examples: 2.18a pavements 2.18b symbolized Notice that in both 2.18a and 2.18b each word is composed of a root, a derivational suffix, and an inflectional suffix. In 2.18a, -ment changes pave to a noun, and thus the -es that indicates plural in nouns can be added. In 2.18b, -ize changes symbol to a verb, and thus the -ed that indicates past in verbs can be added. Suppose we tried to reverse this order of affixation, reasoning as follows: if pave is a verb root, then -ed can be added giving paved, which is still a verb. Now if -ment changes verbs to nouns, why not add it to the verb paved giving the noun *pavedment? But the combination of morphemes indicated by the spelling *pavedment is in fact impossible in English. And so is the combination *symbolsize, which might be formed by adding first an inflectional and then a derivational suffix to the root symbol. Such forms are not unreasonable, nor would they be without a certain usefulness. But they are not in fact possible in English. And thus we have a second criterion for distinguishing between derivational and inflectional suffixes: inflectional suffixes can follow derivational suffixes in words, but derivational suffixes cannot follow inflectional suffixes. Notice that the inflectional suffixes -ed and -es occur only last in the words listed in 2.19: 2.19 pavement symbolize paved symbols symbolizable pavements symbolized symbolizability The morpheme or combination of morphemes to which a derivational suffix is attached we may call its base, and the morpheme or combination of morphemes to which an inflectional suffix is attached we may call its stem. So far, we have seen that derivational suffixes change the part of speech of bases to which they are attached, but inflectional suffixes do not change the part of speech of stems to which they are attached. Secondly, derivational suffixes cannot follow inflectional suffixes, but inflectional suffixes must follow all derivational suffixes. There is also a third difference between these two types of suffixes, a difference that can help you distinguish the one type from the other: Words with derivational suffixes (e.g., pavement and kingdom) are entered separately in the dictionary, but the inflected forms of words, e.g., the plural of a noun or the past tense of a verb, do not have separate dictionary entries. This is the case because derivational suffixes are lexical, i.e., they exist in English precisely to increase the number of words in the language (and so each 19 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR new word that a derivational suffix creates deserves its separate entry in a dictionary). But inflectional suffixes are grammatical, i.e., they exist, not to create new words (the singular and plural forms of a given noun are forms of the same word) but to shape words to fit appropriately into grammatical contexts. There is a sense in which a work does not take on an inflectional suffix until it comes out of the dictionary and is placed in a sentence. (A word like these or three preceding a noun determine that the plural of the noun must appear.) Here is a summary of the three differences between derivational and inflectional suffixes: 2.21 Derivational Suffixes: a Usually change part of speech. b Cannot follow inflectional suffixes. c Words with derivational suffixes have separate dictionary entries. Inflectional Suffixes: a' Never change part of speech. b' Cannot precede derivational suffixes. c' Words with inflectional suffixes do not have separate dictionary entries. ENGLISH DERIVATIONAL AND INFLECTIONAL SUFFIXES Some English Derivational Suffixes Examine the eighteen derivational suffixes and example words in 2.22. They are in six groups of three, based on the change they effect in parts of speech. (Notations like N<V in 2.22c should be read "derives nouns from verbs.") As you examine the words in 2.22, notice two things: First, some derivational suffixes do not meet all three of our criteria of definition; for instance, the suffixes in 2.22a are affixed to noun bases and the resultant words remain nouns. Nonetheless the other two criteria classify these suffixes as derivational. Second, notice that derivational suffixes, like prefixes, do not ordinarily have many pronunciation variants (allomorphs), but they provide reinforcement for our definition of a morpheme as an abstract meaning label because they frequently produce pronunciation variants of morphemes in their bases. Notice how the morphemes sane, vain, and chaste change vowel pronunciation when -ity is affixed: sanity, vanity, chastity. And notice that the "k" sound at the end of public, elastic, and fanatic changes to an "s" sound when derivational suffixes are added: publicity, elasticity, fanaticism. 2.22a N<N -hood neighborhood, sisterhood, bachelorhood, boyhood, maidenhood, knighthood -ship lordship, township, fellowship, championship, friendship, membership, lectureship, kinship -ster gangster, gamester, trickster, songster, punster, mobster, prankster, speedster 20 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR 2.22b N < ADJ/N -ism -ity -ness 2.22c N<V 2.22d V < ADJ/N -al -er refusal, dismissal, upheaval, denial, survival, trial, approval, proposal worker, writer, driver, employer, swimmer, preacher, traveler, teacher, baker -ment arrangement, amazement, puzzlement, judgment, astonishment, pavement -en -ify -ize 2.22e ADJ < N/V idealism, impressionism, fanaticism, dualism, realism, imperialism, romanticism, patriotism sanity, vanity, rapidity, banality, elasticity, ability, actuality, agility, chastity meanness, happiness, cleverness, usefulness, bitterness, brightness, darkness, goodness -ful -ish -able ripen, widen, deafen, sadden, harden, lengthen, deepen, strengthen, neaten beautify, diversify, codify, amplify, simplify, glorify, nullify, Frenchify symbolize, hospitalize, publicize, popularize, modernize, idealize useful, delightful, pitiful, helpful, careful, awful, rightful, sinful, cheerful foolish, selfish, snobbish, modish, hellish, sheepish, Swedish acceptable, readable, drinkable, livable, commendable, comfortable, changeable 2.22f ADV < ADJ/N -ly happily, strangely, oddly, athletically, basically -wise clockwise, lengthwise, weatherwise, educationwise -ward earthward, homeward, eastward PRACTICE 2 (WORKING WITH ENGLISH DERIVATIONAL SUFFIXES) All the words given below end with a derivational suffix. It is possible to sort them out on the basis of the final suffix and make a display similar to the one in 2.22 (immediately above). All of the functional groups in 2.22 except the last one (ADV < ADJ/N) are represented. Sort out the words and make that display. Here are the words: alarmist, authorization, Baptist, capacitate, cellist, certification, Chinese, Christendom, civilization, contestant, creamy, deodorant, earldom, earthen, Elizabethan, exploration, facilitate, famous, flowery, formalization, freighter, fruity, glorification, glorious, hyphenate, icy, Indonesian, informant, inhabitant, Japanese, journalese, juicy, kingdom, leaden, Londoner, meaty, modification, novelist, officialdom, orchestrate, Parisian, participant, poisonous, Portuguese, rainy, Republican, riotous, sandy, silken, stardom, starvation, steamer, stylist, thirsty, traitorous, typist, vaccinate, waxen, wooden FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 2 (WORKING WITH ENGLISH DERIVATIONAL SUFFIXES) a N<N -dom -er Christendom, earldom, kingdom, stardom, officialdom steamer, freighter, Londoner 21 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR b N < ADJ/N c N<V d V<N e ADJ < N/V -ist -ese -(i)an stylist, cellist, Baptist, alarmist, novelist, typist Chinese, Portuguese, Japanese, journalese Indonesian, Parisian, Elizabethan, Republican -ant inhabitant, contestant, informant, participant, deodorant -ation fixation, exploration, starvation, modification, certification, glorification, authorization, formalization, civilization -ate facilitate, capacitate, hyphenate, orchestrate, vaccinate -en -ous -y wooden, leaden, silken, waxen, earthen famous, glorious, riotous, traitorous, poisonous meaty, sandy, creamy, icy, rainy, thirsty, flowery, juicy, fruity English Inflectional Suffixes The eight inflectional suffixes of English are listed in 2.23. The word or phrase given first in parentheses serves both as a name and a rough designation of meaning. Next is the morpheme label, then words which end in the inflectional suffix. Each line represents a variant pronunciation (allomorph) of the suffix itself or an allomorph variant it requires in the pronunciation of certain stems. Examine the lists of examples, preferably by reading them aloud. Notice that 2.23a and 2.23b are noun inflectional suffixes, 2.23c to 2.23f are verb inflectional suffixes, and 2.23g and 2.23h are ordinarily adjective inflectional suffixes (though a few adverbs can also have them affixed). Notice also that many words given to exemplify the past tense inflectional suffix in 2.23d are spelled and pronounced the same as words listed with the past participle inflectional suffix in 2.23e. I shall comment below on this and other aspects of the display in 2.23. 2.23a (plural) -es boys, bags, tails, trains, hams, tacks, bats, cuffs bushes, watches, judges wives, knives, thieves oxen, brethren, children teeth, geese, feet data, criteria, alumni sheep, fish, series 2.23b (possessive) -poss Jim's, Joe's, Mom's, Mr. Moore's Pat's, my wife's, Mike's the judge's, the witch's, the boss's 2.23c (present tense) -prs go/goes, buy/buys, sell/sells take/takes, bat/bats, buff/buffs push/pushes, watch/watches am/is/are, have/has, do/does 2.23d 22 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR (past tense) -pst stayed, tried, behaved, barred walked, stopped, stuffed, watched sighted, banded, reminded chose, rose, spoke, stole, froze threw, knew, grew, slew took, stood, forsook bought, taught, fought cut, let, hit, bet went, did, had, made 2.23e (past participle) -en stayed, tried, behaved, barred walked, stopped, stuffed, watched sighted, banded, reminded bought, let, made taken, eaten, fallen, known broken, chosen, spoken, stolen written, given, driven, risen gone, done, been, seen 2.23f (present participle) -ing coming, going, buying, selling 2.23g (comparative) -er bigger, older, quicker better, worse 2.23h (superlative) -est biggest, oldest, quickest best, worse The plural inflectional suffix, which we have labeled -es, has "z," "s," "ez," and "en" as allomorphs in spoken English, or, when its zero allomorph occurs, it can require a vowel change in a stem (e.g., tooth > teeth), or a change of pronunciation at the end of a stem (e.g., criterion > criteria) -- all of which was discussed earlier in this chapter. We have also noted that the zero allomorph of plural can occur without requiring any change in the stem to which it is attached: the stems of sheep, fish, and series in 2.23a do not change pronunciation in any way when the -es inflectional suffix is added, as in John bought three sheep. Note also that the -es inflectional suffix can cause a variant allomorph of a stem to appear: whereas the words wife, knife, and thief end in an "f" sound, the stems of their plurals end in a "v" sound. Earlier, I defined a morpheme as an abstract meaning label, and I have reemphasized and illustrated that definition throughout this chapter. One reason I have done so is that it has important practical implications. As we move ever more deeply into the details of English grammar later in this book, we will need to refer to word classes such as past participles. When we do, it will be highly efficient to identify them by noting that they end with the -en inflectional suffix, and not have to point out that this suffix may be spelled with the letters en (as in eaten), ne (as in gone), ed (as in arrived), t (as in taught), etc. The point is that grammatical descriptions focus on abstract form and in doing so ignore spelling and pronunciation variants. Thus it is important for you to begin right now to ignore allomorphic variations such as the examples in 2.23 manifest, and to think 23 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR of an inflectional suffix like the plural morpheme as if it were always -es no matter how it might be pronounced or spelled and even if it is not pronounced or spelled at all. The possessive inflectional suffix, labeled -poss, has three pronunciations: "z" as in Jim's, "s" as in Pat's, and "ez" as in judge's. But, again, we can ignore such variations when discussing the behavior of this inflectional suffix and represent the morphemes in these three examples as Jim-poss, Pat-poss, and judge-poss. The present tense inflectional suffix, labeled -prs, presents special problems. Many linguists speak of a "third person singular agreement suffix," which is affixed to a verb in the present tense when the verb is preceded by he, she, it, or a noun that these pronouns can replace. This accounts for the "z," "s," and "ez" pronunciations at the end of some example words in the first three lines of 2.23c; it would also account for is, does, and has in the fourth line: all three "s-like" allomorphs occur after third person singular pronouns and nouns. But these "s-like" sounds add no more meaning to a verb stem than it communicates when preceded by I, we, you, they, or nouns these pronouns can replace. For this reason, we will consider the "z," "s," or "ez" pronunciations to be allomorphs of the -prs morpheme which alternate with a zero allomorph that occurs after I, we, and so forth. Thus the verb in both We eat cheese and He eats cheese is analyzed morphologically as eat-prs. The past tense inflection, which we have labeled -pst, has a considerable number of differently pronounced allomorphs, many of which are exemplified in 2.23d. Notice two general tendencies: (1) a tendency to indicate 'past' by affixing a "d," "t," or "ed" pronunciation to the verb stem, as in stayed, walked, and sighted respectively, and (2) a tendency to indicate "past" by changing the pronunciation of a vowel in the verb stem, as in chose, threw, and took. Some verbs, like bought, combine both tendencies. Some verbs, like cut, call for a zero allomorph and make no change at all. Other verbs seem to manifest the first tendency but also to call for a different pronunciation of the stem: in went, did, had, and made a "d" or "t" pronunciation of the past tense inflectional suffix appears, but the pronunciation of the stem in each case varies somewhat from the ordinary non-past pronunciations (go, do, have, make). The morphological representations of went, did, had, and made are go-pst, do-pst, have-pst, and make-pst respectively. The same kind of analysis is made of those verbs with past tense variants that change a vowel in the stem: chose is analyzed as choose-pst, threw as throw-pst, and took as take-pst. The past participle inflectional suffix, which we have labeled -en, has a familiar variant pronounced "en" or "n" as in taken, broken, written, gone. Notice that broken, written, gone, and the words that accompany them in 2.23e change the pronunciation of a vowel in their stem when the -en inflection is affixed. However, even though the most frequently used verbs of English call for an "en" or "n" allomorph, most English verbs pronounce -en exactly like the past tense inflection. Notice that the first three lines of example words in 2.23e are the same as the first three lines in 2.23d. We may ask what determines whether a given occurrence of stayed, or walked, or made is to be analyzed as stay-pst or stay-en, walk-pst or walk-en, make-pst or make-en. In a later chapter, we shall examine detailed criteria for distinguishing these two inflectional suffixes. Here, I wish only to demonstrate that the distinction is a real one and to discuss a simple analytical procedure that can help you determine which of the two inflectional suffixes occurs in a given word. Notice that in He sighted a UFO the "ed" of sighted clearly means "past", 24 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR but in UFOs are sighted every week nothing about the sentence means "past". Similarly, the "ed" of lived in He lived there last year is clearly "past", but the sentence He has lived there for two years implies that he is still living there, and is thus as much a comment on the present as on the past; we are not likely to say or hear a sentence like He has lived there last year, and the reason is of course that the "ed" of lived in this sentence is not a variant of the past tense inflection but of -en. Here is a procedure that can help you decide whether a given verb stem ending in the letters ed has the -pst or -en morpheme affixed. Find a verb like know, see, choose, take, break, write, or go (whose pronunciation of -en is clearly distinct from -pst) and substitute it for the word in question. If, for instance, go were substituted for live in He has lived there, it would immediately be clear that He has gone there not *He has went there is appropriate, and therefore that lived is to be analyzed as live-en. The present participle inflectional suffix, which I have labeled -ing, presents few difficulties. Aside from the fact that the final "g" sound is sometimes dropped in conversation, it really has no more than one allomorph. The comparative and superlative inflectional suffixes, which I have labeled -er and est respectively, have only a few allomorphic variations. When -er is affixed to the stem good it requires an allomorph of the stem, spelled bett, to appear, and when -est is affixed, yet another allomorph, spelled simply b, appears. But as with the other inflectional suffixes, we will focus on the abstract and analyze the morphemes of better and best as good-er and good-est respectively. Worse and worst would be analyzed similarly as bad-er and bad-est. PRACTICE 3 (WORKING WITH ENGLISH INFLECTIONAL SUFFIXES) Printed below is a passage by Henry David Thoreau with forty words italicized. Each italicized word ends in an inflectional suffix (sometimes with a zero allomorph). Copy the words onto a sheet of paper, and beside each word write the label of the inflectional suffix that is part of the word (-es, -poss, -prs ,-pst, -en, -ing, -er, -est). At a certain season of our life we are accustomed to consider every spot as the possible site of a house. I have thus surveyed the country on every side within a dozen miles of where I live. In imagination I have bought all the farms in succession, for all were to be bought, and I knew their price. I walked over each farmer’s premises, tasted his wild apples, discoursed on husbandry with him, took his farm at his price, at any price, mortgaging it to him in my mind; even put a higher price on it, -- took his word for his deed, for I dearly love to talk, -- cultivated it, and him too to some extent, I trust, and withdrew when I had enjoyed it long enough, leaving him to carry it on. This experience entitled me to be regarded as a sort of real-estate broker by my friends. Wherever I sat, there I might live, and the landscape radiated from me accordingly. What is a house but a sedes, a seat? -- better if a country seat. I discovered many a site for a house not likely to be soon improved, which some might have thought too far from the village, but to my eyes the village was too far from it. Well, there I might live, I said; and there I did live, for an hour, a summer and a winter life; saw how I could let the years run off, buffet the winter through, and see the spring come in. The future inhabitants of this region, wherever they may place their houses, may be sure that they have been anticipated. An afternoon sufficed to lay out the land into orchard, woodlot, and pasture, and to decide what fine oaks or pines should be left to stand before the door, and whence each blasted tree could be seen to the best advantage; and then 25 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR I let it lie, fallow perchance, for a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone. FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 3 (WORKING WITH ENGLISH INFLECTIONAL SUFFIXES) Below is a reprint of the passage presented for analysis in Practice 4. Following each italicized word (in parentheses and boldface type) is the label of the inflectional suffix that is attached to the word. At a certain season of our life we are (-prs) accustomed (-en) to consider every spot as the possible site of a house. I have (-prs) thus surveyed the country on every side within a dozen miles of where I live. In imagination I have bought (-en) all the farms (-es) in succession, for all were to be bought (-en), and I knew (-pst) their price. I walked over each farmer’s (-poss) premises, tasted (-pst) his wild apples (-es), discoursed on husbandry with him, took (-pst) his farm at his price, at any price, mortgaging (-ing) it to him in my mind; even put a higher (-er) price on it, -- took his word for his deed, for I dearly love (-prs) to talk, -- cultivated it, and him too to some extent, I trust, and withdrew (-pst) when I had (-pst) enjoyed (-en) it long enough, leaving (-ing) him to carry it on. This experience entitled me to be regarded (-en) as a sort of real-estate broker by my friends (-es). Wherever I sat (-pst), there I might live, and the landscape radiated (-pst) from me accordingly. What is a house but a sedes, a seat? -- better (-er) if a country seat. I discovered (-pst) many a site for a house not likely to be soon improved (-en), which some might have thought (-en) too far from the village, but to my eyes the village was too far from it. Well, there I might live, I said (-pst); and there I did (-pst) live, for an hour, a summer and a winter life; saw (-pst) how I could (-pst) let the years (-es) run off, buffet the winter through, and see the spring come in. The future inhabitants (-es) of this region, wherever they may (-prs) place their houses, may be sure that they have (-prs) been (-en) anticipated (-en). An afternoon sufficed (-pst) to lay out the land into orchard, woodlot, and pasture, and to decide what fine oaks (-es) or pines should be left to stand before the door, and whence each blasted tree could be seen to the best advantage; and then I let (-pst) it lie, fallow perchance, for a man is (prs) rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone. COMPOUND WORDS We have seen that many English words have more than one morpheme, but in all the examples given so far, all words of more than one morpheme have had only one root, even if combined with assortments of prefixes and suffixes. It is also possible in English for one word to have more than one root, as in words like classroom or blackboard. There are in fact hundreds, perhaps thousands, of such compound words in English. Many of them are well established and entered in dictionaries. Many are recent creations of productive compounding processes. There are really no patterns governing whether compounds are written as one word, or as two words, or with a hyphen. The stress pattern is the surest indicator of compounding: the main stressed syllable in the first word of a compound will be louder than the main stressed syllable in any following words. Here are some examples of compounds in which at least one of the compounded words is a noun and where the whole compound functions like a noun, i.e., typically as HEAD of a noun phrase: 26 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR 2.24a Type: noun + noun (sunrise < "The sun rises.") bee-sting, catcall, daybreak, earthquake, frostbite, headache, heartbeat, landslide, nightfall, rainfall, sound change, toothache 2.24b Type: verb + noun (rattlesnake < "The snake rattles.") crybaby, driftwood, flashlight, glow worm, hangman, playboy, popcorn, stink weed, tugboat, turntable, watchdog 2.24c Type: noun + noun (blood test < "X tests blood.") birth-control, book review, crime report, dress-design, haircut, handshake, meat delivery, office management, suicide attempt, self-control, self-destruction, tax cut, word formation 2.24d Type: noun + noun-er (babysitter < "X sits with the baby") city dweller, factory-worker, gate-crasher, housebreaker, playgoer, sun-bather, theatergoer, daydreamer 2.24e Type: noun + noun (doorknob < "The door has a knob") arrowhead, bedpost, cartwheel, piano keys, shirt-sleeves, table leg, telephone receiver, television screen, window-pane 2.24f (These fit the previous 5 types, but the meanings are not literally related to the components of the compound.) birdbrain, blockhead, butterfingers, egghead, fathead, feather brain, hardhat, hardtop, hunchback, loudmouth, pale face, paperback, pot-belly, scarecrow Here are two types that produce compound past participles and one that produces a compound adjective; all three can function as MODIFIERS in noun phrases: 2.25a Type: noun + past participle (heartfelt < "X feels it in the heart.") airborne, custom-built, handmade, home-made, suntanned, typewritten, thunder-struck, weather-beaten 2.25b Type: adjective/adverb + past participle (quick frozen < "X was frozen quickly.") dry-cleaned, far-fetched, fresh-baked, long-awaited, well-meant, widespread 2.25c Type: noun + adjective (foot sore < "sore in respect of one's foot") airsick, air-tight, camera-ready, carsick, dust proof, duty-free, fireproof, foolproof, homesick, oven-ready, tax-free, war-weary 27 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR PRACTICE 4 (Labeling Morpheme Types) The best way to acquire full and lasting understanding of linguistic categories is to apply them to the analysis of texts. In principle, you should be able to take any text at random -- a paragraph from a favorite book, a favorite poem, or even a page from this book -- and label all of the morphemes in all of the words as examples of the various types of morphemes we have discussed in this chapter. In fact, this is not so easy to do, because it is often very difficult to decide about morpheme divisions in a word. So, instead of trying to label all of the morphemes in the words of some random text, why don't you try to label just some morphemes that I have underlined in a text that I have selected. The next paragraph provides the directions. The text, with numbered lines for reference, follows the directions. Determine which of the following morpheme types are represented by the underlined parts of certain words in the following selection: BR (bound root), FR (free root), P (prefix), D (derivational suffix), -es (plural), -poss (possessive), -prs (present tense), -pst (past tense), -en (past participle), -ing (present participle), -er (comparative), -est (superlative). Then, on a separate sheet of paper, list the line number of each word, copy the word beside it, and then write the appropriate label from the list above immediately after the word. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 In the fall of 1924 Thomas Wolfe, fresh from his courses in play writing at Harvard, joined the eight or ten of us who were teaching freshman composition in New York University. I had never before seen a man so tall as he, so beady-eyed and so ungraceful. I pitied him and went out of my way to help him get adjusted to his work and to make him feel at home. His students soon let me know that he had no need of my protectiveness. They spoke of his ability to narrate a simple event in such a manner as to have them roaring with laughter or struggling to keep back their tears, of his readiness to quote at length from any poet they could name, of his habit of writing three pages of commentary, on a one page theme, and of his astonishing ease in expressing in words anything he had seen or heard or tasted or felt. Indeed, his students made so much of his powers of observation that I decided to stage a little test and see for myself. My opportunity came one morning when the students were slowly gathering for nine-o'clock classes. Upon arriving at the university that day, I found Wolfe alone in the large room which served all the freshman composition teachers as an office. He made no protest when I asked him to come with me out into the hall, and he only smiled when we reached a classroom door and I bade him enter alone and look around. He stepped in, remained no more than thirty seconds, and came out. "Tell me what I see," I said as I took his place in the room, leaving him in the hall with his back to the door. Without the least hesitation and without a single error, he gave the number of seats in the room, designated those which were occupied by boys and those occupied by girls, named the colors each student was wearing, pointed out the Latin verb conjugated on the blackboard, spoke of the chalk marks which the charwoman had failed to wash from the floor, and pictured in detail the view of Washington Square from the windows. As I rejoined Wolfe, I was speechless with amazement. He, on the contrary, was wholly calm as he said, "The worst thing about it is that 28 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR 34 35 36 37 38 I'll remember it all." I felt no surprise whatsoever when, five years after that revealing experience I read Wolfe's first novel, LOOK HOMEWARD ANGEL, and recognized it as perhaps the richest compendium of actually remembered sense impressions which any author had ever committed to writing. PRACTICE 5 (Labeling Morpheme Types II) Here is another text, where the analytical task is the same as in Practice (1): Determine which of the following morpheme types are represented by the underlined parts of certain words in the following selection: BR (bound root), FR (free root), P (prefix), D (derivational suffix), -es (plural), -poss (possessive), -prs (present tense), -pst (past tense), -en (past participle), -ing (present participle), -er (comparative), -est (superlative). Then, on a separate sheet of paper, list the line number of each word, copy the word beside it, and then write the appropriate label from the list above immediately after the word. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Though the truth may not be felt or generally acknowledged for generations to come, the only school of genuine moral sentiment is society between equals. The moral education of mankind has hitherto emanated chiefly from the law of force, and is adapted almost solely to the relations which force creates. In the less advanced states of society, people hardly recognize any relation with their equals. To be an equal is to be an enemy. Society, from its highest place to its lowest, is one long chain, or rather ladder, where every individual is either above or below his nearest neighbour, and wherever he does not command he must obey. Existing moralities, accordingly, are mainly fitted to a relation of command and obedience. Yet command and obedience are but unfortunate necessities of human life: society in equality is its normal state. Already in modern life, and more and more as it progressively improves, command and obedience become exceptional facts in life, equal association its general rule. The morality of the first ages rested on the obligation to submit to power; that of the ages next following on the right of the weak to the forebearance and protection of the strong. How much longer is one form of life to content itself with the morality made for another? We have had the morality of submission, and the morality of chivalry and generosity; the time is now come for the morality of justice. FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 4 (Labeling Morpheme Types) Here is the complete and correct analysis of the text in Practice (1) laid out as specified in the directions for Practice (1). You should of course have worked out your own analyses before consulting the answers given below. (line) (word) (answer) (line) (word) (answer) 1 2 3 3 4 courses joined composition had beady-eyed -es -pst FR -pst D 1 2 3 3 4 writing teaching University seen ungraceful FR -ing D -en P, D 29 WORDS: THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF GRAMMAR 4 6 6-7 9 9 10 11 12 12 13 13 15 17 20 21 24 27 29 30 32 32 33 36 38 pitied students protectiveness roaring struggling readiness writing astonishing words heard felt decided classes protest classroom leaving designated conjugated had rejoiced amazement worst experience impressions FR -es P, D -ing FR FR FR D -es -en FR -pst -es FR FR FR FR BR -pst P D -est P P, D 5 6 8 9 10 10 11 12 12 13 14 16 18 20 23 25 28 29 30 32 33 35 37 38 adjusted had ability laughter tears length pages expressing seen tasted powers slowly alone asked stepped hesitation wearing blackboard failed speechless wholly felt richest committed P FR FR D -es D -es FR -en -en -es D P -pst -pst D -ing FR -en D FR -pst -est BR FEEDBACK TO PRACTICE 5 (Labeling Morpheme Types II) Here is the complete and correct analysis of the text in Practice (2) laid out as specified in the directions. You should of course have worked out your own analyses before consulting the answers given below. (line) (word) (answer) (line) (word) (answer) 1 3 5 7 9 10 13 15 17 18 truth emanated recognize lowest mainly unfortunate exceptional forbearance had morality FR -en BR -est D P P FR -en D 1 4 6 8 9 12 14 16 17 18 acknowledged adapted highest does fitted progressively rested protection submission generosity -en -en -est -prs -en BR -pst BR P D 30