Legal Education in an ODEL Institution

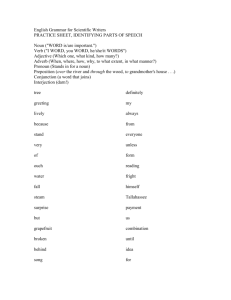

advertisement

Legal Education in an ODEL Institution: Issues, Challenges and Prospects Francisca Anene National Open University of Nigeria anenefrancisca@gmail.com ABSTRACT In this paper, we propose to carry out an assessment of the nature, benefits and challenges of legal education in a Nigerian institution of Open, Distance and ELearning. We shall begin by examining statutory requirements for legal education, the main bodies regulating tertiary legal education in Nigeria and specific skills relevant to legal practice. We shall also consider the nature of the law programme at the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) especially the mode of organisation of students, entry requirements, mode of assessment and challenges encountered in teaching law in an ODEL setting. Introduction The study of law is unique because of the professional nature of the course. Unlike most courses of study, a tertiary degree does not automatically qualify a law graduate to practise as a legal practitioner. Instead, an additional course of training at the Law School is required for a candidate to obtain professional certification as a Barrister-at-Law (BL) which then entitles him or her to practise as a legal practitioner (Solicitor and Advocate) in Nigeria. Furthermore, though tertiary institutions are subject to the regulatory powers of the National Universities Commission, every law faculty is also subject to the regulatory powers of the Council of Legal Education which sets standards for legal education in tertiary institutions and ensures that quality standards are upheld in the training of law students. In line with these standards, the institution is expected to mould students to enable them acquire the skills and qualities required of a legal practitioner. This paper considers the challenges and prospects of Open, Distance, and E-Learning (ODEL) legal education in Nigeria. With particular reference to the School of Law, National Open University of Nigeria, it points out the challenges encountered in the education of law students through pure ODEL and makes suggestions on how to ensure that the School is properly positioned to achieve the goals of qualitative legal education and practice. In the context of this paper, legal education refers to tertiary training of prospective legal practitioners both at the University and the Law School. 1. The law and practice of Legal Education in Nigeria In Nigeria, legal training commences at the university where a prospective legal practitioner obtains a Bachelor of Laws Degree (LL.B) after 5 years full time study1. Thereafter, he is required to undergo further full time training at the Nigerian Law School (the ‘Law School’) for a period of 1 year2. Success at the Law School, entitles a candidate to a qualifying certificate issued by the Council of Legal Education and to be called to the Nigerian Bar (if character requirements are met), with the right to practise as a legal practitioner (Barrister and Solicitor) in any part of the country. In effect, successful completion of a university law programme and award of a Bachelor of Laws Degree (LL.B) qualifies a candidate to reference as a ‘law graduate’ and nothing more3. 1.1 Regulation of Tertiary Legal Education in Nigeria Tertiary legal education in Nigeria is regulated by two major bodies - the National Universities Commission (NUC) and the Council of Legal Education: 1 Or 4 years if the candidate is a Direct-Entry student Or 2 years if the student obtained his LL.B degree from a foreign university 3 Majebi, E. (2009), ‘The Lagos LCDA Palaver: Beyond the Emotions’ available at http://www.vanguardngr.com/2009/08/the-lagos-lcda-palaver-beyond-the-emotions/ last accessed 22/2/2012 2 a. The National Universities Commission The NUC was created under the National Universities Commission Act No. 1 19744. Its responsibilities include: i. advising the President and State Governors, through the Minister, on the creation of new universities and other degree-granting institutions in Nigeria; ii. making recommendations for the establishment of new academic units in existing universities or the approval or disapproval of proposals to establish such academic units; iii. making such other investigations relating to higher education as it may consider necessary in the national interest; iv. making such other recommendations to the Federal and State Governments, relating to universities and other degree-awarding institutions as it may consider to be in the national interest; and v. carrying out such other activities as are conducive to the discharge of its functions under the Act. In addition to the above responsibilities, the NUC is empowered by Section 10(1) of the Education (National Minimum Standards and Establishment of Institutions) Act5, to lay down minimum standards for all universities and other institutions of higher learning in Nigeria, including accreditation of their degrees and other academic awards. b. The Council of Legal Education The Council of Legal Education (CLE) was established under the Legal Education (Consolidation, etc.) Act 1976. Its main responsibility is the legal education of persons seeking to be members of the legal profession6. In order to meet this responsibility, especially since the quality of university education has a direct effect on the quality of candidates for legal education at the Law School, the CLE also exercises the power of accreditation under the Legal Education Act 19627. In addition, the CLE also carries out periodic inspection visits to ensure that law faculties maintain minimum education standards8. 4 CAP N81, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004 5 Cap. E3, Laws of the Federation, 2004 1(2) Legal Education (Consolidation, etc.) Act 7 Section 3 of the Legal Education (Consolidation, etc.) Act CAP L10, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 1990 8 Onolaja, M. O., ‘The Problem of Legal Education in Nigeria’ (2004) available at http://www.alimiandco.com/publications/ACCREDITATION%20AND%20LEGAL%20EDUCATION%20IN%20NIGERIA.pdf last visited 15/2/2012 6Section To be accredited by the CLE, a university law faculty must meet the minimum academic standards of the NUC and the CLE guidelines as to the minimum library requirements, status of law lecturers, student teacher ratio, core subjects, lecture periods and physical/infrastructural facilities of the Law Faculty. Where CLE accreditation of a law faculty is refused, law students who graduate from that University, though they may be awarded LL.B Degrees, will be unable to proceed for further education at the Law School or practise as legal practitioners in Nigeria In Nigeria, as in most other jurisdiction, the legal profession is a conservative and highly regulated profession. To this end, candidates for legal education are subjected to rigorous tests and conditions from the point of admission in the university until they are ultimately called to the Nigerian Bar. These conditions are applicable to all law students regardless of their mode of study i.e. ODL or conventional. Hence, accreditation requirements are the same for all institutions. 1.2. Legal Education and Character Requirements for Legal Practice in Nigeria To qualify as a legal practitioner, candidates are required to meet some requirements which are not necessarily academic in nature. Pursuant to Section 4(1)(c) of the Legal Practitioners Act9, requirements for enrolment as a legal practitioner in Nigeria include Nigerian citizenship, production of a qualifying certificate issued by the Council of Legal Education and satisfaction of the Body of Benchers10 that the candidate is of ‘good character’. To be adjudged of good character, a candidate is screened and found ‘fit and proper’ to be called to the Nigerian Bar. Though this relates to moral character and integrity 11 - somewhat intangible and non-academic qualities, the requirement to be ‘fit and proper’ is so important that a candidate may possess the requisite university degree and Law School qualifying certificate and still be refused the call to the Bar if he is not found to be fit and proper. Moulding of candidates for call to the Nigerian Bar commences in the University. Prior to admission to the Law School, requisite ‘character qualities’ are not necessarily taught in the academic curriculum but are inculcated through interaction and practical training. In practice, character screening is first done in the University. Hence, part of the requirements for admission into the Law School is positive reference from the Dean of the Faculty of Law as to the character of the candidate. Students who have been rusticated or convicted for criminal offences are usually refused admission at the Law School for this reason. 9 CAP L11, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004 The Body of Benchers is a body of legal practitioners of the highest distinction in the Nigerian legal profession. By virtue of Section 3(1) of the Legal Practitioners Act, they are responsible for the formal call to the Bar of candidates seeking to become legal practitioners in Nigeria. 11 See Onalaja supra at page 13 10 2. The Law Programme at the National Open University of Nigeria 2.1 Nature of Study in the National Open University of Nigeria The National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) is the only specialist provider of open and distance education in Nigeria. It is also the largest tertiary institution in terms of student population12. The main focus of the institution being to educate the Nigerian workforce, NOUN has over 50 courses of study from certificate to post graduate level13. At present, there are 40 study centres situated at various locations in Nigeria. The Study centre is designed as the hub of activity in each zone with study materials available for pick up and interactions made possible between students and facilitators, tutors and student counsellors who can offer study support as required. In line with recent advances in distance education, the emphasis in NOUN is on elearning. With the use of the iLMS platform, admission and course registration are initiated online. Upon completion of registration, students are entitled to study materials which they may collect from their study centres or download from the school website. Course materials are written by seasoned experts who may either be academic staff of NOUN or other institutions14. Before any course material is certified suitable for use by students, it is sent to another expert for editing. After it is edited and the editor finds the contents suitable it is then made available to students through the aforementioned channels. Under the ODEL system, teacher-student interaction is minimised and students are expected to interact with their study centre directors and counsellors. Lectures (called ‘facilitation’) are carried out by third party facilitators who are required to explain the topics covered in their course materials to students. Attendance at facilitation sessions is not compulsory and students are expected to form the habit of independent study. With a student population of about 5000, the School of Law has the highest law student population for any Nigerian university. At present, only Bachelor of Laws Degree and Post-Graduate Diploma in Legislative Drafting are available in NOUN. Also, no law degrees have been awarded as the most senior students are currently in their penultimate year (400 Level). 2.2 Assessment in NOUN Assessment in NOUN is of two types: 12 ‘About NOUN – About us’ available at http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/About%20NOUN/contents/About%20us.html last accessed 10/1/2011 13 ‘About NOUN – Facts and Figures’ available at http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/About%20NOUN/contents/facts_figure%20.html last accessed 10/1/2011 14Law course materials may also be written by legal practitioners with requisite knowledge in the particular course, be they in the academia or not a. Four (4) tutor marked assignments (e-TMAs) which are used for mid-term assessment. These carry 30% of the total marks awarded per course. Students are required to complete their TMAs online through their personal portals15. b. E-examinations which carry 70% of total marks awarded per course. E-exams consist of pre-formatted computer based examinations which students are required to take at designated examination centres16. All e-examination questions are multiple choice and fill in the blank questions17 The main advantage of e-assessment in NOUN is that it dispenses with the need for marking of examination scripts and reduces incidences of cheating during examinations. This is largely due to the e-examination software which automatically does the grading immediately after the examination. The software also mixes examination questions so that different examination questions are displayed to students. With the large student population and multiplicity of examination centres for NOUN students, marking and invigilation of examinations would ordinarily pose a problem in terms of cost and manpower. However, these are reduced to the minimum with the above features of the e-examination software. 2.3 Studying Law in NOUN: The Reality The NOUN law programme has proven to be very popular for many reasons. In line with the motto of NOUN which is ‘Work and Learn’, most registered law students are employed adults who wish to take advantage of the flexibility of study available to students in the ODEL setting. Studying in NOUN dispenses with the requirement to attend lectures and/or meet attendance thresholds which obtain in conventional universities. Another attractive feature of the study of law in an ODEL setting is the ability of students to work at their own pace. Students are allowed the flexibility to register for only those courses that they can afford and/or study for at a time. As a result, law students need not complete studies in 5 years as obtains in conventional universities but may take longer depending on time available for learning. Affordability is another attractive attribute of tertiary study in NOUN. Students are allowed to pay per course. Accordingly, a student may only pay for the courses he or she intends to register for at a time and may defer payment for other courses as required. 15 Tutor Marked Assignments (TMAs) are sets of compulsory tests which students are required to complete for continuous assessment purposes. TMAs carry 30% of students’ total score while exams carry 70%. In the past, TMAs were done by written tests and marked by tutors. Presently, students are required to complete TMAs online (e-TMA). 16 See ‘Taking the Electronic Exam at NOUN’ available at http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/e-exam/index.html assessed 28/1/2011 17 Written examinations are being re-introduced with effect from the 1st Semester 2012 examinations. Examinations will consist of multiple choice and fill in the blanks questions as well as essay questions. The above advantages notwithstanding, ODEL students face some challenges occasioned by the unique nature of study. In the first instance, owing to the emphasis on e-learning, computer literacy is a necessity if a student wishes to excel in NOUN. Unfortunately, a large number of NOUN students are not very conversant with the use of the computer. As a result, e-registration and e-examinations pose a problem for such students and incidences of wrong registration are recorded. Furthermore, e-learning depends to a large extent on internet access. Internet penetration is still a major issue especially in the rural parts of the Nigeria. Current internet penetration rate in Nigeria is estimated at 28.9%18. However, internet service is mostly obtainable in metropolitan areas as many areas in Nigeria remain unserved or underserved. Regardless of their location, many students cannot afford personal internet access and may have to depend on cybercafés who also experience major connection challenges from time to time. Such students are also restricted in their access because they can only use cybercafés during working hours. Insufficient bandwidth is another major challenge to effective e-learning. This is further exacerbated by multiple use especially during registration, e-TMA and examination periods which sometimes cause the system to shut down or malfunction. This has a direct effect on the school calendar as registration and eTMAs are known to go on longer than planned to accommodate students who may be disadvantaged as a result of ICT challenges19. Multiple choice e-assessment poses another problem as it precludes in-depth assessment and reduces students’ ability to solve problems under pressure or proffer solutions on the spot. Whilst e-assessment has the advantage of helping students develop speed, they are not suited for teaching the application of theoretical knowledge to real life situations which the law programme requires. Also, students are unable to learn to put their opinions down in coherent and organised form required for legal writing. Students tend to learn in terms of correct or incorrect answers with multiple choice questions. This negates the reality of real life legal situations where there may be no definite course of action but a call to consider all the options and take a position which one must defend. The reality with multiple choice questions is that, even if guesswork is employed, students are bound to get some questions right though they may not have acquired the knowledge the course seeks to pass on. Perhaps the most significant challenge for law students is the unsuitability of pure elearning/e-assessment for the transfer of requisite skills for effective legal practice. Research shows that effective legal practice is influenced such as skills as 18 Source: ‘Africa Internet Usage Statistics’ available at http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats1.htm See, for instance, NOUN announcement on extension of TMA closing date http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/announcements/eTMA%20EXtension.html last accessed 12/2/2012 19 available at intellectual/cognitive skills (analysis, creativity, problem solving), research skills, communication skills (advocacy, writing and speaking), conflict resolution skills and good character (diligence, integrity, passion)20. The reality is that these skills are more easily transferred through face-to-face interaction which does not obtain under pure e-learning. For instance, students cannot be taught how to be ‘fit and proper’ through the pages of course materials or e-examinations. To a large extent, skills like organisation, advocacy and character formation are transferred through communication and interaction which is not readily available to law students in the ODEL setting. Also, multiple choice questions and the lack of written assessments mean that students are unable to learn important legal writing skills or apply theoretical knowledge to real life issues. Students also find it difficult to think on the spot without options being given to them. Though study centres were envisioned as a means of providing some form of staffstudent interaction, the reality is that they are ill equipped for the learning and skills transfer required for law students. This is because of the population of students to which study centre staff are expected to cater and the fact that most study centres do not have staff with any form of legal training on ground. As a result, unique issues such as comportment, character requirements and communication are not given the attention required for proper training of law students. This is further compounded by the fact that all academic staff are located at the NOUN headquarters in Lagos. Whilst law students in Lagos may have some access to academic staff, those in other parts of the country are severely disadvantaged. It may be argued that law students have access to their facilitators (who are all lawyers) and can learn from them. However, facilitation only takes place on weekends and is not compulsory. Furthermore, the School operates a ‘no-facilitation’ policy for courses where students in a particular study centre are less than 50. Owing to the time required for teaching and facilitation, little attention is paid to the transfer of ‘intangible skills’. 3. A Way Forward for Legal Education in NOUN The above challenges notwithstanding, ODEL has come to stay. Most conventional institutions of learning now offer their courses of study through distance education. For such institutions in Nigeria, education is offered through bi-modal systems i.e. some face to face teaching as well as distance education. With the above in mind, a number steps are being taken to improve the quality of learning available to NOUN law students, notwithstanding the nature of NOUN as a pure ODEL institution. In the first instance, it has been proposed that facilitation be made compulsory for all law students and that attendance be taken during 20 Shultz, M. and Zedeck, S. (2008) ‘Identification, Development and Validation Predictors for Successful Lawyering’ available at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/bclbe/LSACREPORTfinal-12.pdf last visited 18/2/2012 facilitation. This will assist students in acquiring proper organisation skills and prepare them for Law School where minimum of 75% attendance is required before law students are allowed to take the Bar Final Exam. The School of Law will also be directly involved in the selection of facilitators and will visit study centres from time to time to observe and supervise facilitation. To promote interaction between staff and students, academic staff from the School of Law have also been assigned to liaise with study centres in various regions. To this end, staff will carry out periodic visits to study centres in their zones and meet/interact with study centre staff and students. Also, the School of Law organises events from time to time for student participation. It is proposed that such events will be organised periodically and held in the various regions for the benefit of students in those regions. It must be pointed out that students have taken the initiative in promoting interactions with academic staff and senior members of the Nigerian Bar. Students in several zones now organise their ‘Law Week’ on an annual basis with several events such as visits to senior members of the profession, law dinners and symposia taking place. There are plans for more staff involvement in such events with a representative of NOUN management and the zonal staff representative being present. Another avenue being explored for skills acquisition is the Moot Competition which is planned for late 2012. To this end, students have been divided into different chambers and given problem questions to consider. Legal practitioners have also been engaged to guide the students and judges/magistrates approached to act as judges during the competition. It is hoped that students will improve their research, communication and advocacy skills through this competition. In the same vein, plans are also in place to have law libraries and moot courts in each study centre. As a first step, a minimum of 6 moot courts and 6 standard law libraries (one per zone) is proposed for construction within the near future. Ultimately, more will be put in place to achieve the goal of having a moot court and law library in each zone. It is pertinent to note here that a major setback to the achievement of the goal of requisite infrastructure for training of law students has been the lack of permanent sites for study centres. Active steps are being taken by NOUN management to deal with this issue. Assessment being a major contributor to the acquisition of requisite legal skills, the e-exam/e-TMA has been given more attention with different options being considered to ensure that students benefit from assessment. With effect from the 1st Semester 2012 examinations, it is proposed that written examinations be included. To this end, students will be required to write the usual multiple choice e- examinations after which they will then tackle some problem/essay questions in written form. In view of minimally interactive nature of ODEL, it has also been suggested that students should be required to take some compulsory tuition in legal ethics. Like the general studies courses, the ethics course could be a non-credit bearing compulsory course which is intended to familiarise students with character requirements of legal practice. To this end, the requirement for regulation dressing is already in place i.e. all study centres are required to insist that students dress conservatively in black and white attires during their visits to their study centres or facilitation. It is hoped that the above steps will help to catalyse further positive action in improving the quality of legal education in NOUN. REFERENCES ‘About NOUN – About us’ available at http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/About%20NOUN/contents/About%20us.html last accessed 10/1/2011 ‘About NOUN – Facts and Figures’ available at http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/About%20NOUN/contents/facts_figure%20.html last accessed 10/1/2011 ‘Africa Internet Usage Statistics’ available at http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats1.htm Education (National Minimum Standards and Establishment of Institutions) Act Cap. E3, Laws of the Federation, 2004 Legal Education Act, CAP L10, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004 Legal Practitioners Act, CAP L11, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004 Majebi, E., ‘The Lagos LCDA Palaver: Beyond the Emotions’ (2009) available at http://www.vanguardngr.com/2009/08/the-lagos-lcda-palaver-beyond-theemotions/ last accessed 22/2/2012 National Universities Commission Act CAP N81, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 2004 Onolaja, M. O., ‘The Problem of Legal Education in Nigeria’ (2004) available at http://www.alimiandco.com/publications/ACCREDITATION%20AND%20LEGAL%20ED UCATION%20IN%20NIGERIA.pdf last visited 15/2/2012 Shultz, M. and Zedeck, S. ‘Identification, Development and Validation Predictors for Successful Lawyering’ (2008) available at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/bclbe/LSACREPORTfinal-12.pdf last visited 18/2/2012 ‘Taking the Electronic Exam at NOUN’ available at http://www.nou.edu.ng/noun/eexam/index.html accessed 28/1/2011 BIBLIOGRAPHY Abdulmumini, A. O. ‘Towards regaining Learning and Correcting Leanings in the Legal Profession in Nigeria’ (2007) CALS Review of Nigerian Law and Practice 14-27 Ehi-Oshio, P. ‘Reform of the Legal Framework for Quality Assurance in Nigerian Universities’ available at http://www.nigerianlawguru.com/articles/labour%20law/REFORM%20OF%20THE%2 0LEGAL%20FRAMEWORK%20FOR%20QUALITY%20ASSURANCE%20IN%20NIGERIAN %20UNIVERSITIES.pdf Majebi, E., ‘The Lagos LCDA Palaver: Beyond the Emotions’ (2009) available at http://www.vanguardngr.com/2009/08/the-lagos-lcda-palaver-beyond-theemotions/ Mamman, T. PhD ‘The Globalisation of Legal Practice: The Challenges for Legal Education in Nigeria’ (2009) being a paper delivered at the 2nd Annual Business Luncheon of S.P.A. Ajibade & Co. – Legal Practitioners Onolaja, M. O. ‘The Problem of Legal Education in Nigeria’ (2004) available at http://www.alimiandco.com/publications/ACCREDITATION%20AND%20LEGAL%20ED UCATION%20IN%20NIGERIA.pdf Shultz, M. and Zedeck, S. ‘Identification, Development and Validation Predictors for Successful Lawyering’ (2008) available at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/bclbe/LSACREPORTfinal-12.pdf