A Nurse Education and Training Board for New Zealand

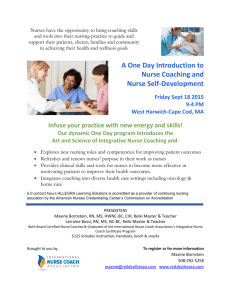

advertisement