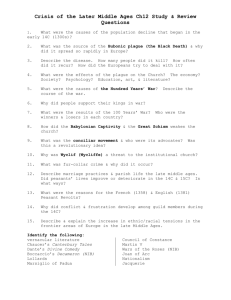

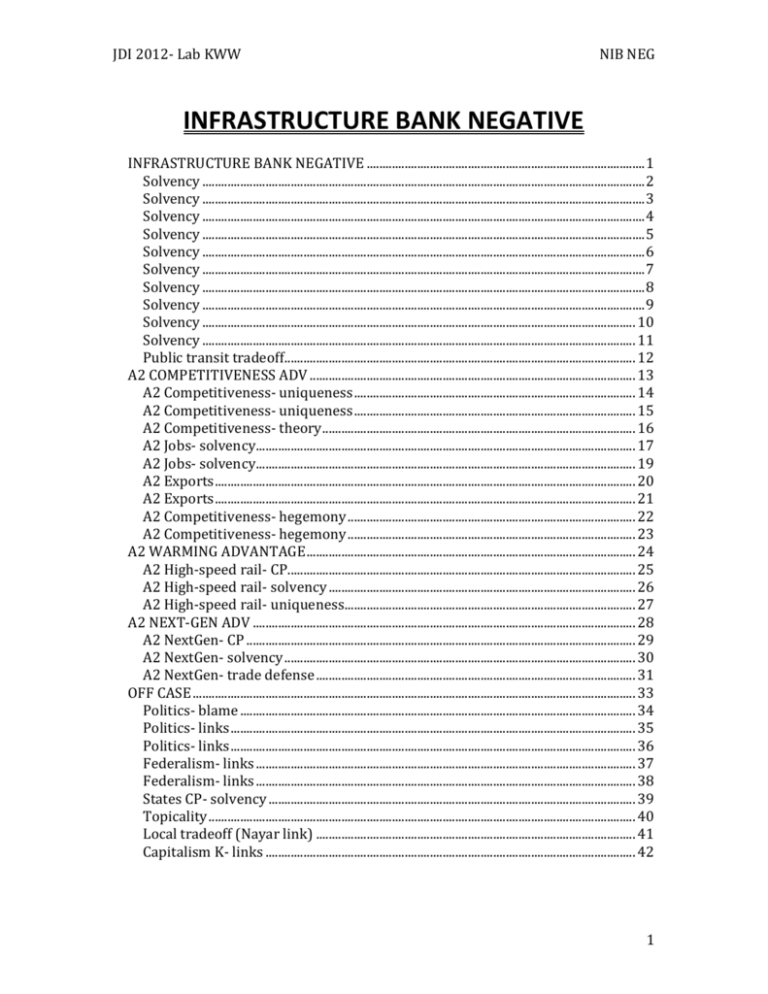

kww bank NEG paper

advertisement