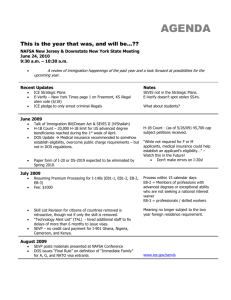

2NC Link Wall – Northwestern

advertisement

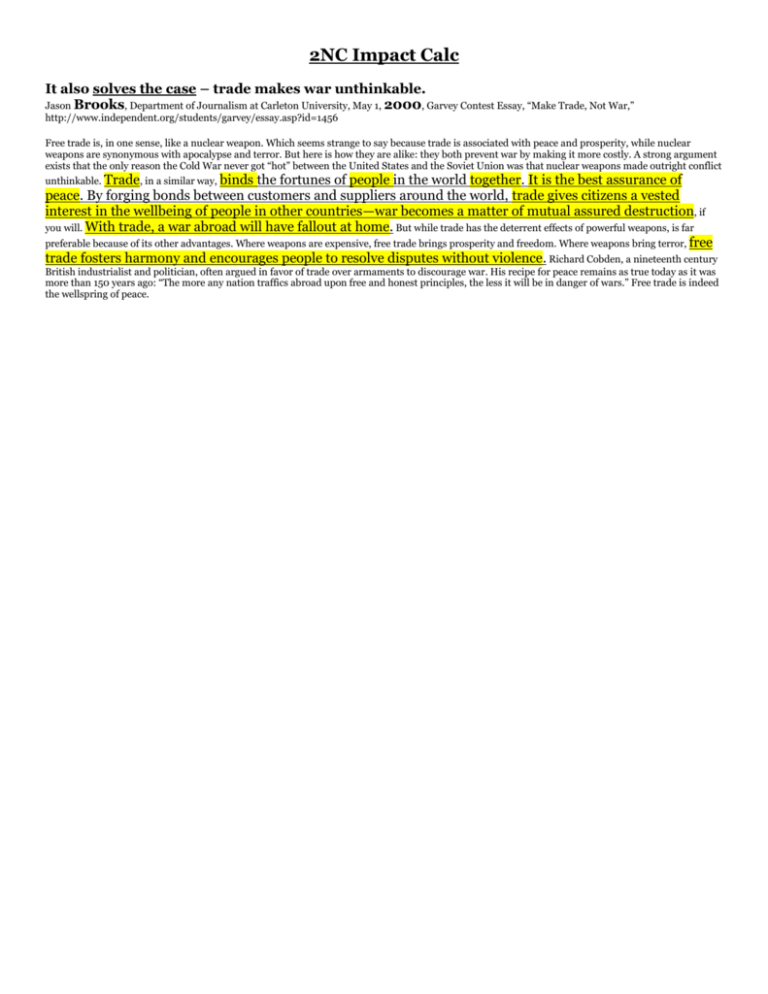

2NC Impact Calc It also solves the case – trade makes war unthinkable. Jason Brooks, Department of Journalism at Carleton University, May 1, 2000, Garvey Contest Essay, “Make Trade, Not War,” http://www.independent.org/students/garvey/essay.asp?id=1456 Free trade is, in one sense, like a nuclear weapon. Which seems strange to say because trade is associated with peace and prosperity, while nuclear weapons are synonymous with apocalypse and terror. But here is how they are alike: they both prevent war by making it more costly. A strong argument exists that the only reason the Cold War never got “hot” between the United States and the Soviet Union was that nuclear weapons made outright conflict unthinkable. Trade, in a similar way, binds the fortunes of people in the world together. It is the best assurance of peace. By forging bonds between customers and suppliers around the world, trade gives citizens a vested interest in the wellbeing of people in other countries—war becomes a matter of mutual assured destruction, if you will. With trade, a war abroad will have fallout at home. But while trade has the deterrent effects of powerful weapons, is far preferable because of its other advantages. Where weapons are expensive, free trade brings prosperity and freedom. Where weapons bring terror, free trade fosters harmony and encourages people to resolve disputes without violence. Richard Cobden, a nineteenth century British industrialist and politician, often argued in favor of trade over armaments to discourage war. His recipe for peace remains as true today as it was more than 150 years ago: “The more any nation traffics abroad upon free and honest principles, the less it will be in danger of wars.” Free trade is indeed the wellspring of peace. 2NC Turns Econ 2. Wage growth is key to job creation. Chris Isidore, CNN Money, “Good job news: Wages are rising. Really.” 3/5/2010, http://money.cnn.com/2010/03/04/news/economy/better_paychecks/index.htm Despite the millions of people who have lost jobs during the past year, there are signs that personal income is increasing. Even a small gain in income is significant. If consumers have more money in their pocket, that can help to boost consumer spending and create the demand that will prompt a resumption of hiring. "At the end of the day, we need income so people can spend money," said Sung Won Sohn, economics professor at Cal State University Channel Islands. "It is a sign that things are beginning to improve." According to the government's monthly job report for February, average hourly earnings have risen by 1.9 percent over the past 12 months. 3. Deflation is the biggest threat to the economy – it turns all of their internals, while their internals are reversible even without the plan. Straits Times, “Beware deflation's spiral,” 11/11/2008, http://www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic/ But what's perhaps more notable in the pace and now the size of interest rate actions is fear of another kind of problem. The global crisis has evolved quickly from financial turmoil into an economic meltdown. And the scale the latter might eventually take is just beginning to sink in. Though we worried just six months ago about high oil prices and other commodity costs pushing up inflation, the looming threat is something more damaging and more difficult to address: deflation. No one likes out-of-control prices. Nevertheless, inflation is the easier of the two opposite price situations to fix. Consumers and industry react reasonably fast to tighter money signals such as interest rate hikes. Faced with the threat of punishment for excessive spending - in the form of a higher cost of money - consumers and businesses react fairly quickly to bring down inflation. Deflation is another matter. Deflation is not just a temporary fall in prices that occasionally occurs. It is a punishing, persistent, downward spiral in prices across a range of goods that makes everyone poorer. Deflation occurs when people and companies hoard cash out of an overwhelming fear of the future. There are already signs this may be happening. The massive October selldown in global stock markets indicates a fall in trust that investments will soon recover, sparking liquidation in favour of cash. In an overarching climate of fear, people stop spending. And as goods are shunned, prices fall. This cuts into companies' earnings until shrinking profits become losses and losses start to pile up. Businesses put off expansion. They fire staff. Rising unemployment rates then erode consumer confidence further, and the cycle starts all over again. Even people and companies with the capacity to spend hold back, calculating that prices will fall further if they can wait. And so on and on, businesses are hit by progressively lower demand for goods. The problem with deflation is that the psychology is difficult to turn around. It's easier to frighten people into cutting spending. Converting deep, visceral pessimism into faith in the future - convincing people to stop hoarding cash - is much harder to accomplish. Japan endured deflation for a decade from the early 1990s. Even with interest rates at zero, people couldn't be persuaded to stop deferring spending. That's why deflation is so frightening. It sticks. In the newest instalment of the global crisis, the source of greatest concern once again is America, where ominous signs are appearing. In October, the US lost 240,000 jobs, bringing the total for the year to 1.2 million. More than half that total occurred in the last three months, moving the unemployment rate up to 6.5 per cent - the highest in 14 years. In the same month of October, weekly wages for those still working grew at less than the rate of inflation. As expected, retail spending has dropped in tandem. If this continues, the entrenchment of price falls will have immense ramifications for the rest of the world. Just as in good times the world looks to the US to be the engine of growth, a dismal American economy threatens to pull everyone down with it. Turns back competitiveness – people will stop looking for jobs in these sectors if the wages get lower, because it’s a bad opportunity Hira 7 [Ron, Professor of Public Policy at MIT, Business Week, “Beware the H1-B Visa”, September 2007] None of this should be surprising given the raison d’etre of modern corporations, maximizing profits. Businesses do not exist to maximize their U.S. workforce or improve competitiveness in the U.S. If companies can lower costs by hiring cheaper foreign guest-workers, they will. If they can hire vendors who hire cheaper foreign guest-workers, they will. And who can blame them? If they don’t take advantage of blatant loopholes, their competitors surely will. Cheap labor and outsourcing explain why the H-1B program is oversubscribed. A sizable share of the U.S. hightech workforce understands this logic, and justifiably views the H-1B program as a threat and a scam. That’s the real danger to U.S. competitiveness. Young people considering a technology career see that industry prefers cheaper foreign guest- workers and that the government uses immigration policy to work against technology professionals. Policymakers need to thoroughly reform these corrupted programs. Legislation introduced by Senators Richard Durbin (DIllinois) and Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) would accomplish this while still giving firms access to the best and brightest. Simply hoping, rather than requiring, corporations to shun the temptation of cheaper labor is not only naïve but also dangerous to the future of U.S. competitiveness. Wages Rising Increased productivity and business confidence are increasing wages. Chris Isidore, CNN Money, “Good job news: Wages are rising. Really.” 3/5/2010, http://money.cnn.com/2010/03/04/news/economy/better_paychecks/index.htm He said companies are adding hours back for workers who had been put on a part-time basis during the worst of the recession. He said there also was a much better environment than a year ago for year-end bonuses that were paid in February. "As things stabilize, businesses are starting to spend a little more," Biderman said. Sohn said strong gains in productivity are also allowing employers to pay their skilled workers more. Productivity rose at nearly a 7% rate in the fourth quarter, according to the government. Wages are rising – key to consumer spending. New York Times 8/2 [Bloomberg News, “Bernanke Says Rising Wages Will Lift Spending”, August 2, 2010] Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke said rising wages would probably spur household spending in the next few quarters, even as weak job gains dragged down consumer confidence. Wages are steadily rising. Paul Vigna, Market Talk, “Newsflash: Wages are Rising (Mind the Caveats),” 8/13/2010, http://markettalk.newswires-americas.com/?p=13186 Okay, here’s a little pinprick of light in an otherwise dark sky: wages are rising. It’s because we’re working longer hours, and because deflation wages, as in earnings adjusted for inflation, in July were up 0.2% from June, as an increase in the workweek offset a decline in hourly wages. Average weekly earnings are up 2% from the recent low hit in October 2009 . On the year, hourly earnings are up 0.4% and weekly earnings are up 1.6%, a function of the fact that we’re all working longer hours. looms over the economy like a goblin, but, hey, a gain’s a gain these days. At least, that’s what the Department of Labor is saying. “Real” 1NC H-1B Link Plan destabilizes high-tech jobs; deflates wages, causes offshoring, and exacerbates loopholes. Ron Hira, assistant professor of public policy at Rochester Institute of Technology, “Beware the H-1B Visa,” 2007, http://www.businessweek.com/debateroom/archives/2007/09/beware_the_h-1b_visa.html The H-1B program has been corrupted by a large and growing share of firms that use it for cheap labor and to facilitate the outsourcing of jobs. Gaping loopholes make it very easy and legal to pay below-market wages. In fact, employers admitted to the Government Accountability Office, Congress’ watchdog agency, that they use the visas to hire less-expensive foreign workers. And examples of approved H-1B applications show how the program undercuts American workers. In 2006, the U.S. Department of Labor rubber-stamped HCL America’s bid to import 75 computer software engineers at $11.88 per hour. The problems don’t stop with cheap labor. The H-1B visa is so critical to the offshore outsourcing industry that India’s Commerce Minister has dubbed it the "outsourcing visa." Seven of the top 10 H-1B employers are offshore outsourcing firms, none of whom hire many Americans, gobbling up tens of thousands of H-1B visas along the way. Rather than preventing it, the program speeds up the outsourcing of high-wage hightechnology jobs. None of this should be surprising given the raison d’etre of modern corporations, maximizing profits. Businesses do not exist to maximize their U.S. workforce or improve competitiveness in the U.S. If companies can lower costs by hiring cheaper foreign guest-workers, they will. If they can hire vendors who hire cheaper foreign guest-workers, they will. And who can blame them? If they don’t take advantage of blatant loopholes, their competitors surely will. Cheap labor and outsourcing explain why the H-1B program is oversubscribed. A sizable share of the U.S. high-tech workforce understands this logic, and justifiably views the H-1B program as a threat and a scam. That’s the real danger to U.S. competitiveness. Young people considering a technology career see that industry prefers cheaper foreign guest-workers and that the government uses immigration policy to work against technology professionals. 2NC Link Wall – Northwestern And, wealthy Americans are uniquely key. Ylan Q. Mui, Washington Post, “Waiting for Deep Pockets to Open,” 9/9/2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2009/09/08/AR2009090803519.html?nav=rss_business In this new era of frugality, well-to-do shoppers have gone into hiding and stowed away their splashy logos. But they may hold the key to a consumer recovery. Affluent shoppers are the most important segment of consumer spending, which in turn drives the national economy. The top 20 percent of the nation's households -- with income of at least $150,000 -- account for 40 percent of all spending, according to government data. That makes them a crucial spoke to any turnaround. "Unless these people turn up, a lot of companies won't turn up," said Milton Pedraza, founder of the Luxury Institute, a consulting firm. "When they are not spending, it definitely impacts all of us in a negative way." A shock to wages will cause financial panic, collapsing the economy. The Economist, “The greater of two evils; Deflation in America,” 5/9/2009, lexis There is something to both fears. But inflation pernicious. is distant and containable, while deflation is at hand and Fears about deflation do not rest on the 0.4% decline in American consumer prices in the year to March. Although this is the first such annual decline since 1955, it is the transitory result of a plunge in energy prices. Excluding food and energy, core inflation is 1.8%. Rather, the worry is of persistent price declines that characterise true deflation. With unemployment nearing 9%, economic output is further below the economy's potential than at any time since 1982. This gap is likely to widen. House prices are not part of America's inflation index but their decline is forcing households to reduce debt, which could subdue economic growth for years. As workers compete for scarce jobs and firms underbid each other for sales, wages and prices will come under pressure. So far, expectations of inflation remain stable: that sentiment is itself a welcome bulwark against deflation. But pay freezes and wage cuts may soon change people's minds. In one poll, more than a third of respondents said they or someone in their household had suffered a cut in pay or hours. The employment-cost index rose by just 2.1% in the year to the first quarter, the least since records began in 1982. In 2003, during the last deflation scare, total pay grew by almost 4%. Does this matter? If prices are falling because of advancing productivity, as at the end of the 19th century, it is a sign of progress, not economic collapse. Today, though, deflation is more likely to resemble the malign 1930s sort than that earlier benign variety, because demand is weak and households and firms are burdened by debt. In deflation the nominal value of debts remains fixed even as nominal wages, prices and profits fall. Real debt burdens therefore rise, causing borrowers to cut spending to service their debts or to default. That undermines the financial system and deepens the recession. From 1929 to 1933 prices fell by 27%. This time central banks are on the case. In America, Britain, Japan and Switzerland they have pushed short-term interest rates to, or close to, zero and vastly expanded their balance-sheets by buying debt. It helps, too, that the world has abandoned the monetary straitjacket of the gold standard it wore in the 1930s. Yet this anti-deflationary zeal is precisely what alarms people like Mr Meltzer. He worries that the price of seeing off deflation is that the Fed will be unable or unwilling to reverse itself in time to prevent a resurgence of inflation. Fair enough, but inflation is easier to put right than deflation. A central bank can raise interest rates as high as it wants to suppress inflation, but it cannot cut nominal rates below zero. Deflation robs a central bank of its ability to stimulate spending using negative real interest rates. In the worst case, rising debts and defaults depress growth, poisoning the economy by deepening deflation and pressing real interest rates higher. Central banks that have lowered rates to nearly zero are now using unconventional, quantitative tools, but their efficacy is unproven. Given the choice, erring on the side of inflation would be less catastrophic than erring on the side of deflation. Our links outweigh their turns – 1. Our link is short term – benefits of immigration take at least 7 years to come to fruition. Peri ’10 (Giovanni Peri University of California, Davis June 2010 The Impact of Immigrants in Recession and Economic Expansion This paper was written for the Migration Policy Institute’s Labor Markets Initiative to inform its work on the economics of immigration. Giovanni Peri is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Davis and a Research Associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He has done research on human capital, growth, and technological innovation. More recently he has focused and published extensively on the impact of international migration on labor markets and on productivity and on the determinants of international migration. He recently received a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation grant for the study of international migration and its impact in the United States and a World Bank grant for the study of return migration in Europe. While data on gross domestic product (GDP) suggest that the worse of the recession is probably over, the US labor market is still deeply depressed. Unemployment rates in the United States are at levels not experienced for two decades. Between January 2009 and January 2010 about 3.9 million jobs were lost.1 It is natural, therefore, to revisit questions about the impact of immigrants on the labor market and on the economy through the lens of the current economic situation. Are the shortrun effects of net immigration2 on native workers’ employment and income less beneficial (or more harmful) if immigrants enter the United States during a recession? Does the economy have the same capacity to “absorb” new workers when immigrants join the US economy in a recession? Do the longrun gains or losses to the US economy from immigration depend on the phase of the cycle during which immigrants enter the country? These questions have become particularly relevant in the last two years and the present report tries to address them. Most (though not all) economic research over the last decade has emphasized the potential gains that result from immigration to the United States. Immigration can boost the supply of skills different from and complementary to those of natives,3 increase the supply of low-cost services,4 contribute to innovation,5 and create incentives for investment and efficiency gains.6 Quantifying these gains is not easy, but steady progress has been made in identifying and measuring them. There is broad consensus that the long-run impact of immigration on the average income of Americans is small but positive.7 In particular, recent studies have identified measurable gains for the highly educated and small, often not significant, losses for less-educated workers. These empirical analyses, however, have focused on the “long run.”8 But the present economic recession and its persistent labor market consequences make the long run seem rather distant, and more pressing concerns about the short run have taken center stage.9 Immigration’s economic benefits mostly result from its effect on immigrant and native workers’ occupational choices, accompanied by employers’ investments and reorganization of the firm. For instance, immigrants are usually allocated to manual-intensive jobs, promoting competition and pushing natives to perform communication-intensive tasks more efficiently. This process, at the same time, reorganizes firms’ structure, producing efficiency gains and pushing natives towards cognitive and communication-intensive jobs that are better paid. These effects may take a few years to unfold fully. In the meantime and before the adjustments take place, do immigrants crowd out natives from the labor market? How long does it take for firms to adjust their investments and organization in order to benefit from the new supply of skills? Are these processes easier and less costly during an economic expansion than in an economic downturn? Until very recently no comprehensive analysis of the short-run effects of immigration on the US labor markets has been possible.10 The reason is that yearly representative data from the Current Population Survey, typically used to analyze production and labor markets, have contained information on the place of birth of individuals only since 1994 (as opposed to the decennial census that has always included that information). Hence, it is only during the last few years that sufficient data has accumulated in order to analyze the short-run (yearly) impacts of net immigration on labor market outcomes. Moreover, between 1994 and 2007, only the mild 2001 recession was observed, providing limited variation over the economic cycle. While several influential academic papers have emphasized how the short-run effects of immigration on wages and employment could be different from long-run effects, those differences were based on theoretical assumptions rather than on empirically estimated evidence. Using empirical methods in line with the best practice used to analyze and quantify the long-run effects of immigration, this report will provide some evidence to inform these questions. It begins by analyzing the short-run impact of immigration on employment, income, and other factors that affect income, such as investments, hours worked, and productive efficiency, examining the speed with which the economy adjusts to accommodate new immigrants. It then extends this analysis to investigate how these shortrun effects, and possibly the medium-run effect (over four or five years), depend on the state of the economy when immigrants enter the labor market. Finally, it discusses the implications the results may have for immigration policy. The results suggest that in the long run, immigrants do not reduce native employment rates, but they do increase productivity and hence average income. This finding is consistent with the broad existing literature on the impact of immigration in the United States. A new analysis of the short-run impacts of immigration, however, finds some mild negative effects: immigration may slightly reduce native employment at first, because the economic adjustment process is not immediate. Lower average income is also likely in the short run. The long-run gains to productivity and income become significant after seven to ten years. The results moreover suggest that the short-run impact of immigration depends on the state of the economy. When the economy is growing, new immigration creates jobs in sufficient numbers to leave native employment unharmed, even in the relatively short run. During downturns, however, new immigrants are found to have a small negative impact on native employment in the short run (but not the long run). The economy does not appear to respond as quickly to new immigrants in terms of new job creation and productivity boosts during recessions. AT: Offshoring New link – plan results in offshoring. Ron Hira, assistant professor of public policy at Rochester Institute of Technology, “Beware the H-1B Visa,” 2007, http://www.businessweek.com/debateroom/archives/2007/09/beware_the_h-1b_visa.html The problems don’t stop with cheap labor. The H-1B visa is so critical to the offshore outsourcing industry that India’s Commerce Minister has dubbed it the "outsourcing visa." Seven of the top 10 H-1B employers are offshore outsourcing firms, none of whom hire many Americans, gobbling up tens of thousands of H-1B visas along the way. Rather than preventing it, the program speeds up the outsourcing of high-wage hightechnology jobs. None of this should be surprising given the raison d’etre of modern corporations, maximizing profits. Businesses do not exist to maximize their U.S. workforce or improve competitiveness in the U.S. If companies can lower costs by hiring cheaper foreign guest-workers, they will. If they can hire vendors who hire cheaper foreign guest-workers, they will. And who can blame them? If they don’t take advantage of blatant loopholes, their competitors surely will. Cheap labor and outsourcing explain why the H-1B program is oversubscribed. Plan will be used to increase offshoring of American labor. Froma Harrop, Real Clear Politics, “Offshoring Is One Sure Thing,” 1/1/2009, http://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2009/01/offshoring_is_one_sure_thing.html When the workers go home, the jobs often go with them. That's a problem for American workers. For the businesses that abuse the program, it's a plan. Indian outsourcing companies account for almost 80 percent of the visa petitions approved for the top 10 participants in the program, according to BusinessWeek. The Indian commerce minister has called H-1B "the outsourcing visa." For the record, Obama also backs issuing more H-1B visas, as does his pick for labor secretary, Hilda Solis. Many American companies have a genuine need for specialized skills from abroad. And the H-1B visa can usefully serve as a bridge for foreign graduates of U.S. universities awaiting their green cards. But it also helps companies replace their skilled American workers with cheaper foreign labor. An example: At the drug maker Pfizer's Connecticut campuses, American information technology (IT) workers train their H-1B understudies. Pfizer's apparent longrange plan is to have some of these jobs performed by guest workers in the United States and others taken overseas, according to The New London Day. It's baffling that the United States would have a program to hasten this humiliating scenario for its workers. And the deeper mystery is why there is so little resistance to it, especially since there are 3 million IT workers in this country. Certainly in this time of massive layoffs there can be no pretense of a labor shortage. "IT workers make up the largest of our science and engineering occupations ," outsourcing expert Ron Hira tells me, "and they essentially have no representation in Washington." Temporary work visas are used to outsource American jobs. Op Ed News, “H1-B Visa Foreign IT Workers and the Immigration Bill,” 5/25/2006, http://www.opednews.com/articles/opedne_runner_060525_h1_b_visa_foreign_it.htm From the very beginning of the Bush Administration U.S. companies have lobbied Congress and President Bush extensively to obtain greater freedom in hiring cheaper foreign technology workers via H-1B and L1 visa programs. Concurrently, U.S. companies have also been busy relocating many technology jobs offshore to India and China where salaries are a fraction of U.S.-base technology salaries and where there is no health insurance cost – because the governments of those countries provide social health care for their citizens. H-1B and L1 visas and the offshoring of American technology jobs often go hand-in-hand, as many companies import H-1B and L1 workers, force US citizens to train them, then offshore the work and finally lay off their U.S. staff. Many H-1B and L1 foreign workers even displace middle and upper level managers who make ongoing hiring decisions. Once in the decision-making positions, H-1B foreign workers are free to claim they can't find qualified American technology workers and must, therefore, hire yet more H-1B foreign workers and send yet more work to their compatriots offshore. AT: Predictability/Uncertainty 2. Flexibility and responsiveness are not mutually exclusive with predictability – the clear standards established by the counterplan solve predictability. Cristina Rodriguez, prof. of law at NYU, “CONSTRAINT THROUGH DELEGATION: THE CASE OF EXECUTIVE CONTROL OVER IMMIGRATION POLICY,” 2010, Duke Law Journal, lexis The regime governing labor migration should be flexible and capable of evolving along with the country’s economic and demographic needs. At the same time, the regime must be relatively stable and predictable, both to allow employers and other economic actors to plan and manage their expectations, and to build public confidence in and acceptance of the system as a whole. These objectives of responsiveness and stability may be in tension with one another, but this tension can be softened. Responsiveness to facts on the ground can help ensure predictability, and stability does not necessarily require that admissions numbers remain constant, only that they reflect evolving needs in a nonarbitrary manner. The salient point for the purposes of this Article is that the decisionmaking structure for immigration policymaking ought to be capable of balancing these objectives. Creating a flexible system equipped to respond to changing circumstances will help promote efficiency and economic growth and create capacity for preventing illegal immigration through nonenforcement-oriented means, thereby helping to mitigate the negative effects of such immigration on U.S. workers and secure ongoing public confidence in the regime. To be flexible, the system must be capable of responding to facts on the ground. The system should be able to adapt to fluctuations in the U.S. labor market, as well as to changes in the economic and demographic circumstances outside the United States that help shape migratory flows, particularly in the American hemisphere. Determining the number and types of immigrants to admit does depend upon value judgments concerning who should become part of the polity, on what terms, and with what effects on existing residents—the so-called “membership decision.” But the process also has a technical dimension that requires databased projections about market dynamics and future economic and social needs. Regulating immigration effectively, therefore, demands a system equipped to evolve in response to the sociology and economy of migration . Predictability, on the other hand, requires avoiding dramatic fluctuations in rules. A predictable system will be somewhat insulated from day-to-day political pressures, whether in the form of interest group lobbying or the antiimmigrant, restrictionist shocks that occasionally arise from the electorate. Predictability not only allows employers and workers to manage their expectations, but also helps facilitate a stable and orderly flow of migration, which in turn helps secure public acceptance of immigration. Predictability and responsiveness need not be mutually exclusive. A regime that adjusts in response to changed circumstances can also be predictable, if interested parties understand how the government anticipates and then adjusts to fluctuating conditions, or if clear standards, set out in advance of the actual decisionmaking, guide changes to the numbers of visas available from year to year. A goal of the decisionmaking structure, therefore, should be to determine how much predictability affected parties require to make decisions about their futures, and to be transparent about the mechanisms used to identify changed circumstances. 3. A flexible cap is good for businesses and innovation. John Yantis, AZ Central, “Tech companies seek to increase cap on visas for foreign-born skilled workers,” 8/1/2010, http://www.azcentral.com/business/articles/2010/08/01/20100801biz-tech-companies-seek-increase-cap-visas-foreign-born-skilled-workers0801.html#ixzz10fSdsQ3G Companies who want to increase the cap say they try to hire Americans first, but they insist the statistics don't lie. "Half the master's and Ph.D. degree graduates are foreign-born students out of our universities, so we would like to recruit them," Cleveland said. "And to have a static cap on H-1Bs at 65,000 is self-defeating and counterproductive. The economy goes up and down. If there's more flexibility in that cap, if there's a market escalator, that is helpful to companies that are on the cutting edge of technology." AT: No Enforcement/DOL Sucks 3. DOL oversight is improving now. Eric Shannon, Business Week, “H-1B visa crackdown?” 3/14/2009, http://network.latpro.com/forum/topics/h1b-visa-crackdown Increased oversight of the program is likely to come on several fronts. The Labor Dept. is tightening review of applications for the work visas, having staffers process requests manually for the first time. Meanwhile, the U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services (USCIS) is more actively investigating companies that receive the visas for potential misuse. Last month, the USCIS and the U.S. Attorney's office in Iowa cooperated on a sixstate raid of companies allegedly abusing the program. Matthew Whitaker, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Iowa, says the resulting 10-count indictment against a New Jersey-based company called Vision Systems Group is just "the tip of the iceberg." Vision Systems did not return calls seeking comment. Senators Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) and Richard Durbin (D-Ill.), two of the program's vocal critics, are pressing for legislative reform as well. They plan to introduce legislation by early April that would require employers to pledge they had attempted to hire American workers before applying for H-1B visas--a step not required under current law. "I want to make sure that every employer searches to make sure there is no American available to do the job," says Grassley.