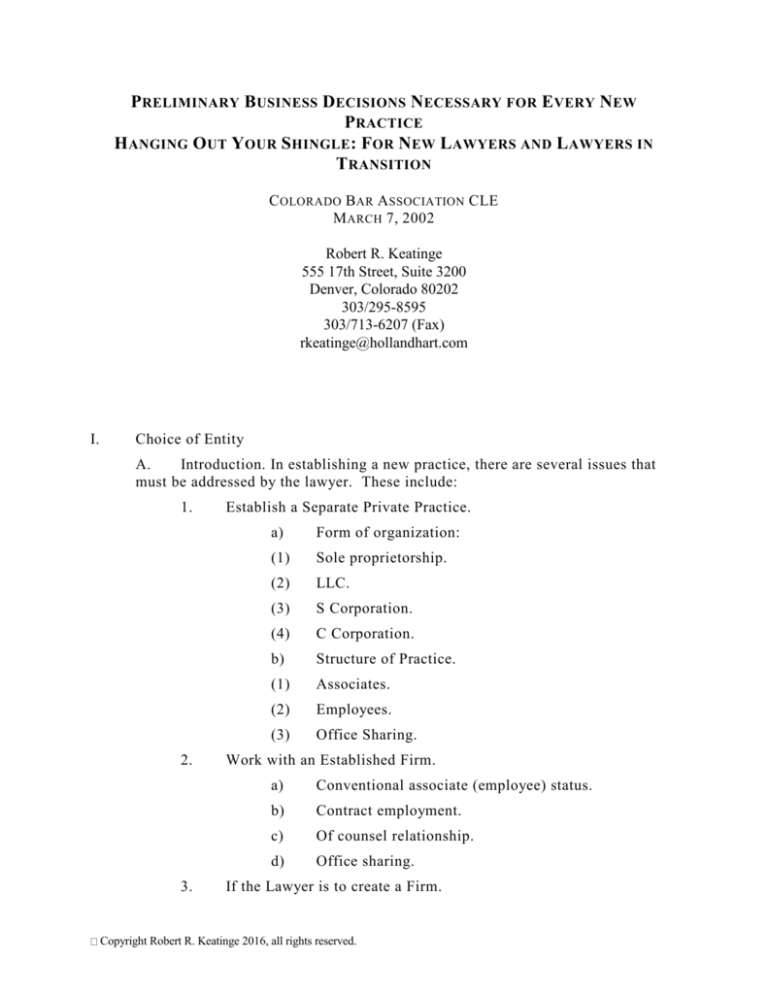

P RELIMINARY B USINESS D ECISIONS N ECESSARY FOR E VERY N EW

P RACTICE

H ANGING O UT Y OUR S HINGLE : F OR N EW L AWYERS AND L AWYERS IN

T RANSITION

C OLORADO B AR A SSOCIATION CLE

M ARCH 7, 2002

Robert R. Keatinge

555 17th Street, Suite 3200

Denver, Colorado 80202

303/295-8595

303/713-6207 (Fax)

rkeatinge@hollandhart.com

I.

Choice of Entity

A.

Introduction. In establishing a new practice, there are several issues that

must be addressed by the lawyer. These include:

1.

2.

3.

Establish a Separate Private Practice.

a)

Form of organization:

(1)

Sole proprietorship.

(2)

LLC.

(3)

S Corporation.

(4)

C Corporation.

b)

Structure of Practice.

(1)

Associates.

(2)

Employees.

(3)

Office Sharing.

Work with an Established Firm.

a)

Conventional associate (employee) status.

b)

Contract employment.

c)

Of counsel relationship.

d)

Office sharing.

If the Lawyer is to create a Firm.

Copyright Robert R. Keatinge 2016, all rights reserved.

B.

II.

a)

Form of organization:

(1)

General partnership.

(2)

LLP.

(3)

LLC.

(4)

S Corporation.

(5)

C Corporation.

b)

Structure of Practice.

(1)

Decision making

(2)

Profit sharing

(3)

Associates.

(4)

Employees.

Business Decisions and Ethics Compliance.

1.

Name.

2.

Engagement letters.

3.

Trust accounts.

4.

Malpractice insurance.

5.

Office location and leasing.

Choice of Organizational Forms and Relationships

A.

General Considerations.

In selecting a form of entity in which to practice law, 1 there are several

considerations that must be weighed including the number of members, 2 the tax

consequences of the form of operation, the desire of the member to limit liability for the

obligations of the Firm, and the ease of operation.

B.

C.

Alternative Organizational Forms for Law Firms

1.

Sole proprietorship

2.

General Partnership

3.

Professional Company.

Types of Professional Companies.

“Firm” is used in the outline to describe the lawyer’s form of practice, even if it is as a

sole proprietorship.

1

“Members” includes the sole proprietor, partners in a partnership, members in an LLC,

and shareholders in a P.C.

2

2

1.

Professional corporation. Unlike many states, Colorado does not

have a separate statute dealing with professional corporations. A

“professional corporation” is a corporation organized under the Colorado

Business Corporation Act. 3

2.

Limited liability company (“LLC”).

3.

Limited liability partnerships (“LLP”).

4.

Joint stock companies? Although Rule 265 authorizes joint stock

companies to organize as professional companies, there is no Colorado

statute describing a joint stock company.

D.

Special Rules for Professional Companies. Under Rule 265 there are

several requirements

E.

1.

Special liability rules.

2.

Insurance requirements.

Alternative relationships of a lawyer within a firm

1.

Partner (shareholder, member)

2.

Associate

3.

Of counsel/special counsel

F.

Single Lawyer - For one lawyer who is going into practice on his or her

own, there are three alternatives:

1.

Sole Proprietorship

2.

Single Member LLC (taxed as a sole proprietorship) - An LLC is a

legal entity formed under the Colorado Limited Liability Act 4 or the LLC

Act of any other state. It is a Professional Service Company within the

meaning of Rule 265, C.R.C.P. 5 and may practice law in Colorado in

compliance with that rule. For federal and state income tax purposes, a

single member LLC is disregarded as an entity separate from the member

who owns it unless the member elects that the LLC be treated as a

corporation.

3.

Professional Corporation (“P.C.”) - A corporation may practice law

if it complies with Rule 265 C.R.C.P. Unlike many states, Colorado does

not have a separate “professional corporation” or “professional

association” statute, so a corporation formed under the Colorado Business

3

C.R.S. § 7-101-101 et seq.

4

C.R.S. § 7-80-101 et seq.

Rule 265 (attached) is a Colorado Rule of Civil Practice. Most rules discussed in this

outline are Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct (C.R.C.P.) and will be referred to

simply as “Rules.”

5

3

Corporation Act may practice of law in Colorado if it complies with Rule

265 C.R.C.P. Like an LLC, and unlike a general partnership or limited

liability partnership, a professional corporation may have one owner.

G.

Multiple Lawyers

1.

Unincorporated Entities

a)

General Partnership - Any association of two or more

persons to carry on a business as co-owners is a partnership,

without the necessity of the partners filing any written

document with the secretary of state or even having a written

partnership agreement. 6 Although not included in the

definition of Professional Service Companies set forth in

Rule 265 C.R.C.P., there is no question that a general

partnership may practice law in Colorado. As with all multi member organizations, all of the members must be lawyers

who are either admitted in Colorado or admitted in some

other state. 7

b)

Limited Liability Partnership (“LLP”) - An LLP is a

partnership (and therefore must have at least two members)

that has registered with the Secretary of State. 8 As an

organization that limits vicarious liability or the members, an

LLP is a Professional Service Company subject to Rule 265

C.R.C.P.

c)

Limited Liability Company (“LLC”) - An LLC, like an

LLP, is an unincorporated business organization that affords

its members protection with respect to vicarious liability. As

such it is a Professional Service Company.

2.

Professional Corporation (“P.C.”) As noted above, a professional

corporation is a Professional Service Company. Unlike an LLC, the tax

treatment and organizational documents of a P.C. will be essentially the

same regardless of whether it has one or multiple members.

H.

Tax Differences

1.

Treatment of the Firm - As noted above, a single member LLC will

be disregarded as separate from its owner unless it elects to be taxed as a

corporation. Any multiple member unincorporated organizations (general

partnership, LLP and LLC) will be treated as a partnership for federal tax

Partnerships are formed under the Colorado Uniform Partnership Act, C.R.S. § 7-64101 et seq.

6

7

Colorado Rules of Professional Responsibility (“CRCP”) 5.4.

C.R.S. § 7-64-1002. Partnerships formed before January 1, 1998 may also register as

LLPs. C.R.S. § 7-60-145.

8

4

purposes unless it elects to be treated as a corporation. A corporation,

including an LLC electing to be treated as a corporation, will be treated as

either a “C corporations” or, if it so elects and meets the qualifications, as

an “S corporation.” A C corporation pays tax on its corporate income 9 and

the shareholder is taxed on any dividends paid to him or her. A

corporation may elect to be an “S corporation” if (1) it has only one class

of stock, (2) all of its owners are individuals (other than nonresident

aliens) or certain trusts or estates, and (3) it has seventy-five shareholders

or fewer. 10 An S corporation is generally not taxed on its income, and all

of the income, loss, and deduction are passed through to the shareholders

when earned by the corporation.

Treatment of the Members - A sole proprietor (including a member

of a single member LLC that has not elected corporate status) will

recognize income and expenses as they are paid or accrued. 11 Members in

LLCs and partners in general partnerships and LLPs are not “employees”

for purposes of federal employment tax. 12 Thus, if an individual is a

partner for federal tax purposes, that person will not be treated as an

employee, regardless of the terminology used to describe the relationship.

In contrast, an employee of a corporation will be treated as such for tax

purposes regardless of whether he or she is also a shareholder. Some of

the consequences of the characterization are set forth below :

2.

While normally a C corporation pays a graduated federal income tax rate on its income

ranging from 15% to 35%, a qualified personal service corporation will be subject to a

flat 35% on all of its income. IRC § 11(b).

9

10

IRC § 1361(b).

A professional services company will want to use the cash receipts and disbursements

method of accounting so that it does not recognize income until the bills are paid. An

accrual method taxpayer must recognize income when the bill becomes payable,

regardless of when it is paid. There was a question about whe ther an LLC or LLP would

be forced to use the accrual method, but, at least for personal services organizations in

which all of the owners actively participate in the business, the matter appears to be

resolved that an LLC or LLP may use the cash method of accounting.

11

12

Rev. Rul. 69-184, 1869-1 C.B. 256.

5

Item

Sole Proprietor

Tax Partnership 13

1

C Corporation

S Corporation

2 or more

1 or more

1 or more

Owner

Partner (in

General

Partnership and

LLP) or Member

in LLC

Shareholder

Shareholder

Sole proprietor

Partners (not

employees)

Employee

Employee (sort of

- see “Deductions

for Health

Insurance

Provided to the

Member by the

Firm”)

Number of

Members

Designation of

Owners

Characterization

of Service

Provider/Owner

for Tax Purposes

Withholding

Deduction of

expenses by

Owner

Partners and sole proprietors are not

subject to withholding, but are required

to pay estimated taxes. 14

A partner or sole proprietor who

expends funds that are not reimbursed

by the partnership, may be able to

deduct those expenses as necessary and

proper

The employer is obligated to withhold

certain amounts from the payments to

the employee. 15

Expenses paid by an employee are

unreimbursed business expenses, which

are subject to substantiation

requirements, 16 and must be taken as an

itemized deduction subject to the 2%

AGI floor 17 and the phaseout of

itemized deductions. 18

In 1997 there were 27,339 partnerships with 133,544 partners (for an average of

approximately 5 partners per firm.

13

IRC § 6654. See also, Treas. Reg. § 1.707-1(c) (“For the purposes of other provisions

of the internal revenue laws, guaranteed payments are regarded as a partner's distributive

share of ordinary income. Thus, a partner who receives guaranteed payments for a period

during which he is absent from work because of personal injuries or sickness is not

entitled to exclude such payments from his gross income under section 105(d).

Similarly, a partner who receives guaranteed payments is not regarded as an employee of

the partnership for the purposes of withholding of tax at source, deferred compensa tion

plans, etc.

14

15

IRC § 3402.

16

Treas. Reg. § 1.162-17.

17

IRC § 67, Temp. Treas. Reg. § 1.67-1T(a)(i).

18

IRC § 68.

6

Item

Sole Proprietor

Tax Partnership 13

C Corporation

S Corporation

Deductions for

Health Insurance

Provided to the

Owner by the Firm

Partners, and sole proprietors are

subject to limitations on deductibility of

health insurance premiums until 2003. 19

Personal use of

Firm Property and

other Fringe

Benefits

Partners, and sole proprietors are

generally not entitled tax favored fringe

benefits 22 such as employer provided

parking. Payments made on behalf of

partners are treated as guaranteed

payments to the recipient partners, 23

while similar payments are not

deductible to a sole proprietor. A sole

proprietor who uses property of Firm is

not subject to tax, but may reduce the

deductibility of the cost of the property.

The tax treatment of the personal use of

partnership property is unclear.

Employees are

entitled to receive

certain fringe

benefits such as

employer parking

tax-free. 24 Except

as provided in IRC

§ 132, personal

use of corporate

property by an

employee is

taxable as wages.

Employment

taxes 26 and self-

A general partner’s distributive share of

ordinary income and from a trade or

Wages are subject to employment taxes,

while dividends are not. Thus, in an S

19

Payments of health

insurance

premiums are

deductible to the

employer 20 and not

included in the

income of the

employee.

Some shareholders

of S corporations

are subject to

limitations on

deductibility of

health insurance

premiums until

2003. 21

Same as for C

corporation except

that a 2 percent

shareholder in an

S corporation is

treated as a

partner for

purposes of the

fringe benefit

rules. 25

Under IRC § 162(i), health insurance premiums are deductible as follows:

For taxable years beginning in calendar year

The applicable percentage is

2002

70 percent

2003 and thereafter

100 percent

20

IRC § 162.

21

Under IRC § 162(i), health insurance premiums are deductible as follows:

For taxable years beginning in calendar year

The applicable percentage is

2002

70 percent

2003 and thereafter

100 percent

22

IRC § 132 (f)(5)(E) (“employee” does not include persons who are self -employed).

23

Rev. Rul. 91-26, 1991-1 C.B. 184.

24

IRC § 132.

25

IRC § 1372(a)(2).

For 2002, each of the employer and the employee are subject to an employment tax of

6.2% on the first $84,900 of wages paid to the employee. IRC §§ 3101(a), 3111(a). In

26

7

Item

employment

taxes 27

Sole Proprietor

Tax Partnership 13

business conducted by the partnership

(other than dividends, interest, and real

estate rentals) is “net earnings from

self-employment” (“NESE”), and

subject to self-employment taxes. 28

NESE does not include a limited

partner’s share of income or loss,

except with respect to guaranteed

payments for services 29

C Corporation

S Corporation

corporation, the shareholders can within

certain limitations, allocate income

between amounts subject to selfemployment taxes and amounts that are

exempt. 30

addition, each of the employer and employee must pay a Medicare hospital tax on the

total (uncapped) amount of wages equal to 1.45%. IRC §§ 3101(b), 3111(b).

For 2002, self-employment taxes are imposed on net earnings from self-employment at

the rate of 15.3 on the first $84,900 and 2.9% on amounts in excess of $84,900. IRC §

1401, 66 Fed. Reg. 54,047 (October 25, 2001)) (fixing the Old-Age, Survivors, and

Disability Insurance (OASDI) contribution and benefit base to be $84,900 for 2001).

Self-employed persons are entitled to an above the line deduction equal to ½ of the self employment taxes. IRC § 164(f). This deduction, when applied to an individual at the

highest marginal rate (39.6%) reduces the effective rate for this tax to 12.2706% for

self-employment income to $84,900 and 2.3258% for self-employment income in excess

of $84,900.

28

IRC § 1402(a).

27

29

IRC § 1402(a)(13) currently provides:

there shall be excluded the distributive share of any item of

income or loss of a limited partner, as such, other than

guaranteed payments described in section 707(c) to that

partner for services actually rendered to or on behalf of the

partnership to the extent that those payments are established

to be in the nature of remuneration for those services;

The Limited Liability Company Task Force of the ABA Tax Section is considering

alternative legislative proposals for modifying the determination of a partner’s net

earnings from self-employment. The current suggestion for modifying IRC §

1402(a)(13) is as follows (Note, this proposal has not been approved by the ABA

Section of Taxation as of the date of this outline (June 1, 1999), and does not represent

a position of the Taxation Section):

IRC § 1402(a)(13)(A) there shall be excluded the distributive

share of net any item of income or of a limited partner, as

such, attributable to capital. other than guaranteed payments

described in section 707(c) to that partner for services

actually rendered to or on behalf of the partnership to the

extent that those payments are established to be in the nature

of remuneration for those services.

8

Item

Tax Treatment of

Compensation to

Members

Sole Proprietor

Tax Partnership 13

Self-employment

income

Self-employment

income (probably)

C Corporation

S Corporation

Wages (subject to

adjustment for

unreasonably high

Wages (subject to

adjustment for

unreasonably low

(B) Safe harbors For purposes of subparagraph (A), the

following amounts shall be treated as income attributable to

capital:

(i) the amount, if any, in excess of what would constitute

reasonable compensation for services rendered by such

partner to the partnership, or

(ii) an amount equal to a reasonable rate of return on unreturned

capital of the partner determined as of the beginning of the taxable

year.

(C) Definitions. For purposes of subparagraph (B) –

(i) Unreturned Capital. The term “unreturned capital” shall mean the

excess of the aggregate amount of money and the fair market value

as of the date of contribution of other consideration (net of liabilities)

contributed by the partner over the aggregate amount of money and

the fair market value as of the date of distribution of other

consideration (net of liabilities) distributed by the partnership to the

partner, increased or decreased for the partner’s distributive share of

all reportable items as determined in section 702. If the partner

acquires a partnership interest and the partnership makes an election

under section 754, the partner’s unreturned capital shall take into

account appropriate adjustments under section 743.

(ii) Reasonable rate of return. A reasonable rate of return on

unreturned capital shall equal 150 percent (or such higher rate as is

established in regulations) of the highest applicable federal rate, as

determined under section 1274(d)(1), at the beginning of the

partnerships tax year.

(D) The Secretary shall prescribe such regulations as maybe

necessary to carry out the purposes of this paragraph;

The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants is considering a similar

proposal.

The Service has assessed employment taxes where S corporation shareholders have

paid themselves unreasonably low salaries (actually, the cases deal with situations in

which no wages were paid). Spicer Accounting, Inc. v. United States, 918 F.2d 90 (9th

Cir. 1990); Radtke, S.C. v. United States, 712 F. Supp. 143 (E.D. Wis. 1989), affd. per

curiam 895 F.2d 1196 (7th Cir. 1990); Dunn & Clark v. Commissioner, 853 F. Supp.

365, 367 (D. Idaho 1994); Joly v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 1998-361 (1998).

30

9

Item

Sole Proprietor

Tax Rates on

Business Income 31

Withholding on

Payments to

Members

I.

Tax Partnership 13

Federal individual tax rates run between

15% and 38.6%. 32

Members required to make estimated

tax payments.

C Corporation

S Corporation

compensation)

compensation)

Federal corporate

tax rates run a flat

35% on all income

and federal income

taxes on dividends

and wages run

between 15% and

38.6%. 33

Federal individual

tax rates run

between 15% and

38.6%. 34

Corporation required to withhold on

amounts characterized as wages.

Liability Protection and Rule 265

1.

Entities not providing Liability Protection. Two business

organizations, the general partnership and the sole proprietorship, expose

their members to full vicarious liability for the obligations of the Firm.

Thus, a general partner or a sole proprietor will be personally obligated to

repay any liability of the Firm, regardless of whether the Firm’s obligation

arises out of an error or omission in representing a client or is simply an

obligation to a business creditor. 35

2.

Professional Service Companies. Rule 265 C.R.C.P. sets forth the

rules with which a Professional Services Company must comply in order to

practice law in Colorado. A “Professional Service Company” is an LLP,

LLC, or P.C. (or joint stock company) that is engaged “solely in the

practice of law,” and which maintains a certain level of insurance.

3.

Hybrid Organizations. Because Rule 265 allows Professional

Service Companies to be members in another Professional Service

Company, and because it is possible for Professional Service Companies to

31

Income of the business after deducting wages to Members.

The top marginal individual rate is 38.6% for 2002 and 2003, 37.6% for 2004 and

2005, and 35% until at least 2010.

32

The top marginal individual rate is 38.6% for 2002 and 2003, 37.6% for 2004 and

2005, and 35% until at least 2010.

33

The top marginal individual rate is 38.6% for 2002 and 2003, 37.6% for 2004 and

2005, and 35% until at least 2010.

34

CUPA does require that, in the absence of other agreement, a creditor of a firm

organized as a partnership must first try to collect the Firm’s obligation from the Firm

before proceeding against the partner individually. C.R.S. § 7 -64-307(4).

35

10

be partners in partnerships. 36 As such, it is possible to have a partnership

with professional corporations as members. While many of the tax reasons

for such an arrangement no longer obtain, this arrangement may be useful

to allow different partners to have differing economic and liability

arrangements. Although partners are individually liable for the obligations

of the partnership, if a P.C. is a partner in a partnership, the P.C.’s policy

only has to protect against the errors and omissions of the employees of

the P.C., not against the errors and omissions of employees or other

partners of the partnership. 37

J.

Alternative Business Relationships

1.

Employment Relationships.

a)

Issues for employed attorney. The employment

agreement between an employed attorney should address

many of the same issues addressed in the partnership

agreement such as compensation, performance expectancies,

as well as certain matters that may be important to the

attorney such as: Amount and type of errors and omissions

coverage;

b)

The support that the attorney will get, including

secretarial services, library access, continuing education,

vacation arrangements, marketing support;

c)

Compensation, including bonuses.

2.

Employees. Attorneys other than members of the Firm are

generally employees, subject to the terms and conditions of the

employment agreement between the Firm and the attorney.

a)

Contract Attorney. This term is often used to describe

an attorney who is not a partner and generally is not on

partnership track. It is sometimes used to characterize a

relationship different than that of an associate.

b)

Contract Partner/Non-Equity Partner - This term

describes an attorney who does not share in the profits of the

partnership but is given the title “partner” in order to obtain

the prestige that accompanies the title.

3.

Of Counsel/Special Counsel. The term “of counsel” is defined

under the ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility as a

relationship other than that of a partner or associate. 38 The Model Rules of

36

Colorado Bar Association Ethical Opinion 55 (undated with an add endum dated 1995).

37

Gutrich v. LaPlante, 942 P.2d 1266 (Colo. App. 1996).

ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility Disciplinar Rule 2 –102(A)(4)

defined the “of counsel” relationship as follows:

38

11

Professional Conduct have no similar provision. ABA Formal Opinion

90–357 defines an “of counsel” relationship as that of: (1) the part-time

practitioner; (2) a retired partner of the firm who is not an active

practitioner but remains associated with the firm on a consultant basis; (3)

a probationary partner, usually a person who comes into the firm laterally

with the expectation of being a partner after a short time; and (4) the

permanent status of a person who is more than an associate but less than a

partner.

4.

Temporary Attorney - Some lawyers and law firms engage

temporary attorneys who are not regular members of firm. An ABA formal

opinion provides that where the temporary lawyer is performing

independent work for a client without the close supervision of a lawyer

associated with the law firm, the client must be advised of the fact that the

temporary lawyer will work on the client's matter and the consent of the

client must be obtained. This is so because the client, by retaining the

firm, cannot reasonably be deemed to have consented to the involvement

of an independent lawyer. On the other hand, where the temporar y lawyer

is working under the direct supervision of a lawyer associated with the

firm, the fact that a temporary lawyer will work on the client's matter will

not ordinarily have to be disclosed to the client. A client who retains a

firm expects that the legal services will rendered by lawyers and other

personnel supervised by the firm. Client consent to the involvement of

firm personnel and the disclosure to those personnel of confidential

information necessary to the representation are inherent in the act of

retaining the firm. 39

5.

K.

Office Sharing

a)

Ethical Issues, see Formal Opinion 89 (attached)

b)

Office Sharing Arrangement

(1)

Rent

(2)

Secretarial Staff

(3)

Phone and Utilities

(4)

Listing of Names

(5)

Equipment

The Agreement of the Members - See Partnership Agreement Attached

1.

Partnership Agreement or other Agreement of the Members

A lawyer may be designated "Of Counsel" on a letterhead if he has a continuing

relationship with the lawyer or law firm other than as a partner and associate.

American Bar Association Standing Committee on Ethics Formal Op. No. 88 -356, at

10 (Dec. 16, 1988).

39

12

a)

Types of Agreements - In a partnership or LLP, the

agreement is known as the “partnership agreement,” 40 in an

LLC, it is known as the “operating agreement” 41 in a

corporation, the agreement may be reflected in the articles of

incorporation, the bylaws, a shareholders agreement or an

employment agreement.

b)

Purposes of the Agreement - the partnership

agreement is the “constitution” of the Firms, it provides the

general agreement of the partners on important matters and

the method of deciding other matters. As such it should be

flexible enough to provide guidance on how to address

unexpected issues.

2.

Contents - The following items should be addressed in the

Agreement of the Members:

a)

The identity of the members and how new members

will be added.

b)

The manner in which day to day decisions will be

made.

c)

The manner in which profits are to be shared and

distributions made.

d)

The duties of the members.

e)

The manner in which major changes will be decided.

(1)

Amendment of the agreement.

(2)

Dissolution.

(3)

Merger.

III.

Trust Account and Banking Relationships - See CRPC Rule 1.15.

IV.

Insurance Issues.

A.

Health Insurance.

B.

Disability Insurance.

C.

Life Insurance.

D.

1.

Personal.

2.

Key Person.

Retirement Accounts.

40

C.R.S. § 7-64-103.

41

C.R.S. § 7-80-108.

13

V.

VI.

Malpractice Insurance.

A.

Claims-made vs. occurrence.

B.

“Tails.”

C.

Activities covered.

D.

Loss Prevention Benefits.

Office Considerations.

A.

VII.

Significant considerations.

1.

Location.

2.

Facilities.

3.

Cost.

4.

Term.

B.

Home Office.

C.

Staffing Issues.

D.

Consultants.

MDP, MJP, Ancillary Business and the Future of the Practice of Law

A.

Multi-Disciplinary Practice (“MDP”)

1.

Defined: An arrangement or organization some but not all of the

owners of which are lawyers, and some but not all of the services of which

constitute legal services.

2.

Current status: Unsettled. While the ABA House of Delegates has

soundly rejected changes in the rules to accommodate MDP while

preserving the core values of the practice of law, many states, including

Colorado, have committees looking at rule changes to permit coownership

by non-lawyers. In addition, many strategic alliances among professionals

exist which operate as de facto MDPs. See Colorado Bar Association

Ethics Committee Formal Opinion 98 (“Dual Practice”) (December 14,

1996) discussing attorneys who are engaged in more than one profession.

B.

Multi-Jurisdictional Practice (“MJP”)

1.

Defined: The practice of law by a lawyer in a jurisdiction in which

the lawyer is not licensed.

2.

Current status: Many states have statutes and court rules

prohibiting the unauthorized practice of law. A recent survey of Colorado

lawyers indicates that many lawyers currently practice across state lines

and would support changes in the rules that permit such practice. The

Colorado Supreme Court is currently considering rule changes that would

14

permit temporary practice and in-house practice in Colorado by lawyers

licensed in other jurisdictions. 42

C.

Ancillary Business

1.

Defined: Services that may not constitute the practice of law,

provided by a law firm or an organization related to a law firm.

2.

Current status: Unsettled, note that Rule 265 provides that a

professional company must be organized “solely for the purpose of

conducting the practice of law.” See also Colorado Bar Association Ethics

Committee Formal Opinion 98 (“Dual Practice”) (December 14, 1996)

discussing attorneys who are engaged in more than one profession.

D.

Other Thoughts on the Future of the Practice of Law

1.

Movement to technology as a manner of delivering information and

legal services.

2.

Greater competition in the delivery of legal information. Greater

movement to the delivery of knowledge rather than information. 43

See Cynthia Covell, Douglas Foote, Robert R. Keatinge, Proposed Amendments to

C.R.C.P. 228 and the Cross Border Practice of Law, Colorado Lawyer, January 2002.

42

43

See Susskind, Transforming the Law, Oxford 2000.

15

Rule 265. Professional Service Companies

I.

A. Attorneys who are licensed to practice law in Colorado may do so in the form of

professional corporations, limited liability companies, limited liability partnerships, registered

limited liability partnerships, or joint stock companies, herein collectively referred to as

“professional companies,” permitted by the laws of Colorado to conduct the practice of law,

provided that such professional companies are established and operated in accordance with the

provisions of this Rule and the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct. The provisions of this

Rule shall apply to all professional companies having as shareholders, officers, directors,

partners, employees, members, or managers one or more attorneys who engage in the practice of

law in Colorado, whether such professional companies are formed under Colorado law or under

laws of another state or jurisdiction. All professional companies conducting the practice of law

in Colorado shall comply with the following requirements:

1. The name of the professional company shall contain the words “professional

company,” “professional corporation,” “limited liability company,” “limited liability

partnership,” or “registered limited liability partnership” or abbreviations thereof such as “Prof.

Co.,” “Prof. Corp.,” “P.C.,” “L.L.C.,” “L.L.P.,” or “R.L.L.P.” that are authorized by the laws of

the State of Colorado or the laws of the state or jurisdiction of organization. In addition, the

name of the professional company shall always meet the ethical standards established by the

Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct for the names of law firms.

2. The professional company shall be established solely for the purpose of conducting

the practice of law, and the practice of law in Colorado shall be conducted only by persons

qualified and licensed to practice law in the State of Colorado.

3. The professional company may exercise all of the powers and privileges conferred

upon such types of entities by the laws of the State of Colorado or other state or jurisdiction of

organization but only for the purpose of conducting the practice of law pursuant to this rule and

the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct.

4. The articles of incorporation, partnership agreement, operating agreement, or other

governing document or agreement of the professional company shall provide, and each of the

shareholders, partners, or members shall agree, that each of them who is a shareholder, partner,

or member of the professional company at the time of the commission of any professional act,

error, or omission by any of the shareholders, officers, directors, partners, members, managers, or

employees of the professional company shall be jointly and severally liable to the extent provided

by this Rule for the damages caused by such act, error, or omission; provided, however, that the

governing document or agreement may provide that any such shareholder, partner, or member

who has not directly and actively participated in the act, error, or omission for which liability is

claimed shall not be liable, except as provided in clause (e) of this subparagraph I.A.4, for any of

the damages caused thereby if at the time the act, error, or omission occurs the professional

Copyright Robert R. Keatinge 2016, all rights reserved.

company has professional liability insurance which meets the following minimum standards:

(a)The insurance shall insure the professional company against liability imposed upon

it arising out of the practice of law by attorneys employed by the professional company in their

capacities as attorneys.

(b)Such insurance shall insure the professional company against liability imposed upon

it by law for damages arising out of the professional acts, errors, and omissions of all

nonprofessional employees.

(c)The policy may contain reasonable provisions with respect to policy periods,

territory, claims, conditions, and other matters.

(d)The insurance shall be in an amount for each claim of at least $100,000 multiplied

by the number of attorneys employed by the professional company, and, if the policy provides for

an aggregate top limit of liability per year for all claims, the limit shall not be less than $300,000

multiplied by the number of attorneys employed by the professional company; provided,

however, that no professional company shall be required to carry total limits of insurance in

excess of $500,000 for each claim or be required to carry an aggregate top limit of liability for all

claims per year of more than $2,000,000.

(e)The policy may provide for a deductible or self-insured retained amount and may

provide for the payment of defense or other costs out of the stated limits of the policy. In either

or both such events, the liability assumed by the shareholders, partners, or members of the

professional company shall include the amount of such deductible or retained self-insurance and

shall include the amount, if any, by which the payment of defense costs may reduce the insurance

remaining available for the payment of claims below the minimum limit of insurance required by

this Rule if the ultimate liability for the claim exceeds the amount of insurance remaining to pay

for it.

(f)A professional act, error, or omission is considered to be covered by professional

liability insurance for the purpose of this subparagraph I.A.4 if the policy includes such act, error,

or omission as a covered activity, regardless of whether claims previously made against the

policy have exhausted the aggregate top limit for the applicable time period or whether the

individual claimed amount or ultimate liability exceeds either the per claim or aggregate top

limit.

5. The liability assumed by the shareholders, partners, or members of the professional

company pursuant to subparagraph I.A.4 is limited to liability for professional acts, errors, or

omissions which constitute the practice of law and shall not extend to actions or undertakings

that do not constitute the practice of law. The liability assumed by the shareholders, partners, or

members of the professional company pursuant to subparagraph I.A.4 may be pursued only by a

citation brought under C.R.C.P. 106(a)(5) after entry of a judgment against the professional

company. Liability, if any, for any and all actions or undertakings, other than professional acts,

2

errors, or omissions, shall be as generally provided by law and shall not be changed, affected,

limited, or extended by this Rule.

B. Each attorney practicing law in Colorado as a shareholder, director, officer,

member, manager, partner, or employee of a professional company, whether formed under the

laws of the State of Colorado or under the laws of any other state or jurisdiction, shall comply

with the following standards of professional conduct:

1. No such attorney shall act or fail to act in a way which would violate any of the

Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct adopted by this Court. The professional company shall

also comply at all times with all standards of professional conduct established by this Court and

with the provisions of this Rule. Any violation of or failure to comply with any of the provisions

of this Rule by the professional company may be grounds for this Court to terminate or suspend

the right of any attorney who is a shareholder, director, officer, member, manager, or partner of

such professional company to practice law in Colorado in the form of a professional company.

2. Nothing in this Rule shall be deemed to diminish or change the obligation of each

attorney employed by the professional company to conduct that attorney’s practice in accordance

with the Colorado Rules of Professional Conduct promulgated by this Court. Any attorney who

by act or omission causes the professional company to act or fail to act in a way which violates

such standards of professional conduct or any provision of this Rule shall be deemed personally

responsible for such act or omission and shall be subject to discipline therefor.

II. Any professional company established for the purpose of conducting the practice of law must

comply with all of the following additional requirements:

A. Except as provided in paragraph II.B and II.C, all officers, directors, shareholders,

partners, members, or managers of the professional company shall be individuals who are duly

licensed by either the Supreme Court of the State of Colorado or some other state or jurisdiction

to practice law either in the State of Colorado or in such other state or jurisdiction and who at all

times own shares or other equity interests in the professional company in their own right. In

addition, all other employees or representatives of the professional company who practice law

shall be duly licensed by either the Supreme Court of the State of Colorado or some other state or

jurisdiction to practice law in the State of Colorado or in such other state or jurisdiction.

B. A professional company may have one or more shareholders, partners, or members

which are professional companies so long as each such shareholder, partner, or member is

established and operated in accordance with the provisions of this Rule and the Colorado Rules

of Professional Conduct.

C. A professional company may have directors, officers, or managers who do not have

the qualifications described in paragraph II.A, but no director, officer, manager, or employee of a

professional company who is not licensed to practice law either in the State of Colorado or

elsewhere shall exercise any authority whatsoever over any of the professional company’s

3

activities relating to the practice of law.

D. Provisions shall be made requiring any shareholder, partner, or other member who

withdraws from or otherwise ceases to be eligible to be a shareholder, partner, or member of the

professional company to dispose of all shares or other equity interests therein as soon as

practicable either to the professional company or to any person having the qualifications

described in paragraph II.A. Provisions may be made for the redemption or disposition of shares

or other equity interests over a reasonable period of time so long as the withdrawing shareholder,

partner, or member does not exercise any management or professional function during such

period of time.

E. A professional company may adopt retirement, pension, profit -sharing (whether cash

or deferred), health and accident insurance, or welfare plans for all or some of its

employees, including lay employees, provided that such plans do not require or result in

the sharing of specific or identifiable fees with lay employees and provided that any

payments made to lay employees or into any such plan on behalf of lay employees are

based upon their compensation or length of service or both rather than upon the amount

of fees or income received.

4

89

OFFICE SHARING - CONFLICTS, CONFIDENTIALITY, LETTERHEADS AND

NAMES

Adopted September 21, 1991.

Amended April 18, 1992.

Introduction and Scope

The Colorado Bar Association Ethics Committee (“Committee”) has received

inquiries concerning ethical issues presented in office sharing situations of lawyers.

Sharing office space is a common, time-honored method of association among practicing

lawyers. It provides reduced operating costs, collegiality among lawyers and a

convenient source of lawyers to fill in for one another when one is sick or on vacation.

At the same time, office sharing arrangements allow lawyers to retain the financial

independence and control over the practices valued by sole practitioners not sharing

offices. While deriving benefits from office sharing arrangements, lawyers should be

aware of the potential ethical problems such arrangements may present.

Syllabus

This opinion addresses the following ethical concerns in office sharing

arrangements: conflicts of interest and duty of loyalty to clients; preservation of client

confidences; and use of letterheads and names. Factual patterns illus trating common

problems are included to demonstrate the application of general ethical principles to

specific areas of concern.

Attorneys sharing offices may represent clients with conflicting interests only if

such representation does not violate the applicable disciplinary rules within Canon 5.

For example, the financial, business or operating relationship among the lawyers must

not create differing interests of the lawyer which could cause a violation of DR 5 101(A). See also, Rule 1.7. In some situations, office sharing lawyers who represent

clients with actual or potential conflicting interests to each other may be prohibited from

representing those clients. See, DR 5-105(D); Proposed Model Rule 1.10. Where such

representation causes a conflict described by DR 5-105, the office sharing lawyers may

nevertheless represent clients with conflicting interests if it is obvious to each lawyer

that he or she can adequately represent the interest of the client, and if each client

consents to the representation after full disclosure of the possible effects such

representation may have on the exercise of the lawyer’s independent professional

judgment. DR 5-105(C).

In addition to potential conflict problems, office sharing attorneys must take

precautions to avoid disclosure of client confidences in all matters. The Code, Canon 4;

Proposed Model Rule 1.6. Office sharing lawyers should be particularly attentive when

lawyers or their employees have access to each other’s file storage and/or have shared

reception areas, staff, computer and telephone equipment. Important factors to consider

in protecting confidentiality are sharing of staff and equipment and the overlap in the

areas of practice between the lawyers. The more shared equipment and staff or the larger

the overlap in areas of practice, the greater potential for inadvertent disclosure of client

confidences and secrets and that such disclosure will be harmful to the client.

Copyright Robert R. Keatinge 2016, all rights reserved.

Finally, office sharing lawyers must scrupulously avoid any representation to the

public that there is a professional corporation, partnership, associate or other law firm or

employment relationship among them when no such relationship exists. DR 2 -102(C);

Proposed Model Rule 7.5; CBA Formal Opinions 8, 9 and 50. Otherwise, an office

sharing attorney misleads the public that the other lawyer in the office bears some

additional responsibility for the office sharing attorney’s legal services and standards.

Opinion

A. Conflicts of Interest

The Code requires that lawyers have undivided loyalty to t heir clients and that the

lawyers be free from influences which may affect such loyalty. DR 5 -101(A) and (B);

DR 5-105; Allen v. District Court, 519 P.2d 351 (Colo. 1974); EC 5-1 and EC 5-19.

Accordingly, office sharing attorneys should avoid representing clients with actual or

potential conflicting interests to each other since this practice is rife with ethical

problems.1 “Except with the consent of his [or her] client after full disclosure, a lawyer

shall not accept employment if the exercise of . . . professional judgment on behalf of

[the] client will be or reasonably may be affected by his [or her] own financial, business,

property or personal interests.” DR 5-101(A). DR 5-105 requires a lawyer to decline

proffered employment if it would likely involve him or her in representing differing

interests, unless this actual or potential conflict is waived by the client after full

disclosure. Finally, Canon 9, which requires a lawyer to avoid “even the appearance of

professional impropriety,” further militates in favor of lawyers in an office sharing

situation avoiding conflicts of interest. While the representation of adverse parties in an

office sharing situation may not be a per se violation of Canon 9, lawyers should

recognize that representation in such circumstances is fraught with ethical pitfalls. See,

e.g., CBA Formal Opinion 75, adopted June 20, 1987 (spousal conflicts).

1. Financial Arrangements and the Exercise of Independent Judgment

When lawyers share office space, they usually have financial rel ationships with

each other. Examples of such financial relationships include:

A young lawyer beginning a practice may commit to work a certain number of

hours each month for an established attorney who provides free office space and

services in exchange;

Office sharing lawyers may be jointly liable on a lease and may share other

overhead costs as well; and

One attorney may own or rent offices which he or she rents to a second

attorney.

Shared financial arrangements between and among office sharing lawye rs can be

very advantageous to all of the lawyers involved. However, these financial arrangements

can create a potential leverage to be used by one lawyer against the other, especially in

situations where the attorneys represent clients with actual or pote ntial conflicting

interests. These financial arrangements may require that either or both lawyers decline

representing the clients or alternatively, in some such situations, representation may be

permitted only after full disclosure to each client, followed by client consent. DR 5105(A). Even with disclosure and consent, should the lawyers proceed to represent

clients with conflicting interests, they must be certain that the common financial

2

arrangements will not interfere with their exercise of independen t professional

judgment, and will not adversely affect their duty of loyalty. DR 5 -105(C). If each

lawyer properly determines that his or her independent professional judgment reasonably

will not be affected by the financial arrangement, and the other issu es regarding

conflicts and confidentiality have been satisfactorily addressed, the lawyers may

represent the clients.

2. Imputed Disqualification

Although office sharing lawyers generally are not considered “a firm,” analysis

under DR 5-105(D) and Proposed Model Rule 1.10 is helpful in determining whether a

lawyer should disqualify himself or herself by declining the representation of a potential

client. The vicarious disqualification provisions of DR 5-105(D) apply to a partner or

associate or “any other lawyer affiliated with” the lawyer who is required to decline

employment. For purposes of imputed disqualification, this latter phrase reasonably may

be interpreted to apply to office sharing attorneys in some circumstances. Similarly, the

Comments to Proposed Model Rule 1.10 make clear under the Rules that office sharing

attorneys under certain circumstances may be considered to be part of “a firm”:

Whether two or more lawyers constitute a firm within this definition can

depend on the specific facts. For example, two practitioners who share office space

and occasionally consult or assist each other ordinarily would not be regarded as

constituting a firm. However, if they present themselves to the public in a way

suggesting that they are a firm or conduct themselves as a firm, they should be

regarded as a firm for the purposes of the rules. The terms of any formal agreement

between associated lawyers are relevant in determining whether they are a firm, as is

the fact that they have mutual access to information concerning the clients they

serve. Furthermore, it is relevant in doubtful cases to consider the underlying

purpose of the rule that is involved. A group of lawyers could be regarded as a firm

for purposes of the rule that the same lawyer should not represent opposing parties in

litigation, while it may not be so regarded for purposes of the rule that information

acquired by one lawyer is attributed to the other.

Ethics opinions issued by other states have relied upon rules of imputed

disqualification to disqualify one office sharing lawyer from representing a particular

client when the adverse party is represented by another lawyer in the same suite of

offices. See, Wisconsin Bar Opinion E-86-2 (3-86); Alabama Bar Opinion 83-178

(12/21/83) (lawyer may not represent a wife in action related to divorce in which lawyer

sharing office represented husband); Illinois Bar Opinion 783 (6/28/82) (criminal

defense attorneys are precluded from representing defendants being prosecuted by space

sharing municipal prosecutor). See generally, Sharing Office Space, ABA/BNA Lawyers

Manual on Professional Conduct 91:604-605.

In order to avoid ethically impermissible conflicts of interest, lawyers in office

sharing situations may wish to take several precautionary steps. F irst, they should

ascertain, to the extent possible, the nature of the practices of other office sharing

attorneys in the same suite to determine whether any actual or potential conflicts are

likely to arise. In some office sharing situations, the attorneys represent clients in

completely different areas of practice and there is little if any chance of a conflict

3

arising. If the office sharing lawyer determines areas of conflict may exist,2 the lawyer

can either decline employment in all cases of possible conflict or take certain

precautions to ensure that his or her office sharing arrangement will not be considered

an “affiliation” or “firm” for purposes of imputed disqualification. The more lawyers in

an office sharing arrangement present themselves to the public in a way suggesting they

are a firm, the more likely the vicarious disqualification rules will apply.

To reduce the likelihood of being viewed as a firm, the office sharing attorney

should take various measures to ensure that his or her practice i s completely separate

and distinct from that of other office sharing attorneys and that there are no unnecessary

financial entanglements. A lawyer must restrict access to client files and information

from other office sharing lawyers. If, however, the lawyer wants another lawyer in the

suite to provide coverage, then the clients should consent to such arrangement and

restricted access may not be necessary. See, EC 4-2. Additionally, the lawyers should

further protect the client by restricting computer, telephone, fax machine and copier

access. When there is a reasonable possibility of a conflict of interest arising, the lawyer

may also wish to discuss the office sharing situation with the client and inform the client

in writing of specific procedures he or she has taken to ensure there will be no actual

conflict of interest.

Notwithstanding these precautions, the lawyer should be aware that there is a

substantial risk of disqualification if in fact he or she is “too closely involved with” the

other office sharing attorneys or their clients. See, Dean v. American Security Insurance

Co., 429 F.Supp. 3 (N.D. Ga. 1976), aff’d mem., 559 F.2d 1214 (5th Cir.), reversed on

other grounds, 559 F.2d 1036 (5th Cir. 1977). See also, McMahon v. Seitzinger Bros.

Leasing, Inc., 506 F.Supp. 618, 619 (E.D. Pa. 1981) (attorney disqualified from

representing plaintiff where attorney shares office space with a law firm which

represented defendant in a substantially related matter); CBA Informal Opinion I,

October 10, 1972 (inappropriate for attorney to appear before the Board of County

Commissioners if he shares office space with County Attorney).

B. Presentation of Confidences and Secrets of a Client

An office sharing attorney, like all lawyers, must take precautions to prevent

disclosure of client confidences and secrets on all matters. Canon 4 of the Code. Office

sharing arrangements often include situations where attorneys share or have access to

one another’s file cabinets, reception area, conference room, law library, staff,

computers, telephones, and/or fax machines. In each of these situations, there is an

opportunity for inadvertent disclosure of client confidences or secrets. To minimize such

inadvertent disclosure, each office sharing attorney must assume responsibility for the

conduct of his or her staff and ensure that the staff not disclose or use any client

confidences or secrets. See, DR 4-101(D). ln addition, “absent consent of the client, the

lawyer should not seek counsel from another lawyer if there is a reasonab le possibility

that the identity of the client or his [or her] confidences or secrets would be revealed to

such lawyer.” CBA Formal Opinion No. 75, citing EC 4-2. Moreover, the office sharing

lawyer should avoid “indiscreet conversations” concerning his or her clients. EC 4-2.

To ensure confidentiality, the office sharing lawyer may need to take certain

measures in addition to restricting access to files, such as restricting access between the

4

telephone systems of the separate practices; arranging the rece ption area such that one

lawyer’s secretary is not able to overhear confidences from another lawyer’s clients; not

leaving confidential materials in the copier area or library for inspection by other

lawyers; using security devices to restrict access to computers; avoiding sharing of staff

to the extent possible, particularly secretaries and paralegals; and informing clients of

the space sharing arrangement and of measures undertaken to avoid any compromise of

confidentiality. See, Indiana Opinion 8 of 1985 (undated).

The need to ensure confidentiality exists in all cases, but is especially great when

office sharing lawyers represent clients with potential or actual conflicting interests, as

discussed above.

C. Names and Letterheads

DR 2-102(C) provides that “a lawyer shall not hold himself [or herself] out as

having a partnership with one or more other lawyers unless they are in fact partners.”

Similarly, Proposed Model Rule 7.5(f) states that “lawyers may state or imply that they

practice in a partnership or other organization only when that is the fact.” The comment

to Colorado’s Proposed Model Rule 7.5 states:

With regard to paragraph (f), lawyers sharing office facilities, but who are not

in fact partners, may not denominate themselves, as for example , “Smith & Jones,”

for that title suggests partnership in the practice of law.

This Committee has held that “it is improper to use the term ‘associates’ to

describe lawyers, not employees, who share office space and some costs but do not share

in responsibility and liability for each other’s acts.” CBA Formal Opinion No. 50

(adopted November 29, 1972). See also, CBA Formal Opinions 8 and 9 (both adopted

June 26, 1959).

Lawyers sharing offices are also prohibited from using a common trade name

under the provisions of DR 2-102(B). Similarly, Colorado’s Proposed Model Rule 7.5(b)

prohibits lawyers from practicing under a trade name. (Note, however, that the ABA

Model Rule 7.5(a) allows lawyers to use a trade name, and in this respect Colorado’s

Proposed Model Rules differ).

Furthermore, any misleading name is prohibited by DR 2-101(B). See, Proposed

Model Rule 7.5(b). In some cases, ethics committees have approved a list of attorneys

on a sign outside a suite of offices, when the sign states “law offices,” fo llowed by the

statement “not a partnership, professional corporation, or professional association.” See,

Dallas Bar Opinion 1983-3 (1/28/83); Indiana Bar Opinion 8, 1980. The Committee

believes that such a designation may be helpful in appropriate circumst ances to ensure

that members of the public do not believe that office sharing attorneys in fact are

practicing in a partnership or professional corporation. However, the Committee also

believes that lawyers may list their names on a sign outside an office suite under the

term “law offices,” as long as there is otherwise no indication that the lawyers in that

suite are practicing in a partnership or professional corporation.

In addition, DR 2-102(A) and (B) and Proposed Model Rule 7.5(a) extend the

prohibition against false and misleading names to letterheads, professional cards, and

directory lists. See generally, CBA Formal Opinion 84 (adopted February 26, 1990). As

with firm names, office sharing lawyers must take care to ensure that their letterheads,

5

business cards and directory listings do not falsely or misleadingly suggest to the public

that a partnership exists. Thus, office sharing lawyers should not use joint letterheads

that state, for example, Alice B. Smith, Attorney at Law and Harry R. Jones, A ttorney at

Law, because the use of such letterheads could easily be interpreted as suggesting the

existence of a partnership. The same result should obtain for joint business cards or

directory listings. ABA/BNA Lawyers Manual on Professional Conduct, 91: 601-603.

D. Fact Patterns

To facilitate the analysis of the application of these rules to office sharing

situations, four scenarios are considered:

Scenario One

The first scenario involves office sharing attorneys who have the same area of

practice, namely domestic relations. One attorney is representing the husband, while the

other seeks to represent the wife in a divorce. In this scenario, there is a heightened

likelihood of conflict of interest arising. The lawyers must disclose the office sharing

arrangement to the clients, and allow the clients the opportunity to decide whether to

waive an actual or potential conflict. See, Formal Opinion 75. In order for the client to

intelligently waive any actual or potential conflict, the client must be informed of all

relevant information regarding the conflict and the safeguards for preservation of

confidences and secrets.3 If adequate safeguards are in place, as discussed below, the

second office sharing lawyer may be able to exercise independent professional judgment

on behalf of the wife. On the other hand, if adequate safeguards are not in place, the

office sharing lawyers may be considered “affiliated” or “a firm” for imputed

disqualification purposes. In that event, the second office sharing lawyer may be

required to refrain from representing the wife, or, indeed, both lawyers might be

required to withdraw from representing their clients. If the office sharing lawyers have

taken steps to restrict access to each other’s client files, telephone calls, and fax

transmissions and the lawyers do not share the same staff, there is a reduced likelihood

of access to confidential information.

In sum, where office sharing lawyers are practicing in the same or similar areas,

the need for avoiding conflict of interest and for maintaining client confidentiality is

greatest.

Scenario Two

In this scenario the office sharing lawyers have completely different types of

practices, such as criminal defense, workers’ compensation, and bankruptcy. There is

little if any, likelihood of the office sharing lawyers representing clients with actual or

potential conflicts. However, if one of the office sharing lawyers were to discover after

the commencement of representation that another attorney in the same suite was

representing a client with actual or potential conflicting interests, then this attorney is

required to disclose this fact immediately to his or her client. The client then would

need to consent to the disclosed actual or potential conflict, or the lawyer would be

forced to withdraw. In this situation, it is still important that the lawyers establish

procedures to avoid disclosure of client confidences; however, the risk that an

inadvertent disclosure of client confidences would be harmful is not as great. See, CBA

Formal Opinion 75.

6

Scenario Three

In this scenario the office sharing lawyers practice in the same or similar areas.

Because each is a sole practitioner, they agree to fill in for one another when the other is

sick, on vacation, or out of town. The need for conflict checks in this situation is

heightened because the agreement among the office sharing lawyers to fill in for one

another strongly suggests that at least for some purposes these lawyers are operating as

“a firm,” and thus are subject to the rules of imputed disqualification in both the Code

and the Rules. A conflict check system is advisable to ensure that other lawyers in the

suite are not representing clients with actual or potential conflicts.

Moreover, the office sharing attorneys must include a provision in retainer

agreements that other office sharing attorneys may substitute for the retained attorney

when necessary, and, therefore, client confidences may be revealed. By virtue of such a

provision, the client thereby consents to representation by his or her retained lawyer and

by the other office sharing lawyers. The effect of such a provision in the retainer

agreement would be to extend the notion of “a firm” and to authorize the office sharing

lawyer to disclose the client’s identity and otherwise share information concerning the

client’s legal matter with other office sharing attorneys. The requirement for avoiding

inadvertent disclosure of confidential client matters through access to case files, fax

transmissions and other means would be eliminated, because the client in effect would

have consented to representation by more than one office sharing attorney.

Scenario Four

The office sharing lawyer leases space from another office sharing lawyer. The

two lawyers represent clients with an actual or potential conflict with the other. In this

scenario, as discussed above, if a conflict arises, the office sharing lawyer may be

required either to decline employment or to provide full disclosure to the client,

accompanied by the client’s consent, because either lawyer’s independent professional

judgment could be compromised by the existence of the landlord tenant relationship.

Thus, if the lawyer landlord were to threaten the lawyer tenant, directly or indirectly,

with unfavorable treatment under the lease relationship in the event of an unsuccessful

outcome for the landlord’s client, the lawyer tenant might not be able to exercise his or

her professional judgment properly on behalf of the client. Similarly, an attorney

landlord might not be able to properly exercise professional judgment on the client’s

behalf if the lawyer tenant threatened to move out in the event his or her client didn’t

fare well. Such conduct by the landlord or the tenant attorney also would violate DR l 102(A)(5). In these situations, it is proper for each lawyer to disclose the lease

relationship and its implications for the representation to the client so that the client

may intelligently decide whether to continue representation and waive any possible

Canon 5 violation.

Conclusion

Office sharing is a common way for lawyers to share facilities, to reduce

operating overhead and to create collegiality among lawyers. However, lawyers should

be aware of the ethical issues inherent in office sharing situations, particularly conflicts

of interest, protection of client confidences and secrets, and proper letterheads and

names in order not to mislead clients and others. Because of the variety of office sharing

7

relationships, the different client interests at stake in each instance, and th e interplay of

the several ethical duties, determining the proper course of conduct for the lawyers to

follow will depend upon a thorough analysis of the facts in each situation.

1. The Committee recognizes there may be almost an infinite variety of offi ce sharing

arrangements. In some situations, such as a large suite of nearly independent lawyers, the office sharing

attorneys may be able to avoid potential conflicts and exercise independent professional judgment on

behalf of their clients. In more typical, smaller office sharing situations, with shared use of facilities, it

may be much more difficult to avoid an actual or potential conflict of interest.

2. It may be difficult for a lawyer to determine in all instances whether an actual conflict or

potential conflict exists because even the identity of a client may be confidential. See, e.g., EC 4-2. An

office sharing lawyer may wish to seek a waiver of confidential identity from his or her clients so that a

conflict check can be made. Given the circumsta nces of office sharing lawyers, the Committee believes

that the practice of doing conflict checks in and of itself should not be construed as making them more

like a firm for purposes of imputed disqualification.

3. In order to ascertain whether an actual or potential conflict exists, because the lawyers have

the same type of practices, the office sharing attorneys may wish to consider establishing a regular

conflict check procedure. If this were done, however, office sharing lawyers should obtain a waiver from

their clients of the client’s identity so that such a conflict check could be made. See, EC 4-2.

8

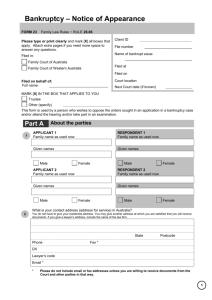

RULE 1.15. SAFEKEEPING PROPERTY;

INTEREST-BEARING ACCOUNTS TO BE ESTABLISHED FOR THE BENEFIT

OF THE CLIENT OR THIRD PERSONS OR THE COLORADO TRUST

ACCOUNT FOUNDATION; NOTICE OF OVERDRAFTS; RECORD-KEEPING

(a) In connection with a representation, an attorney shall hold property of

clients or third persons that is in an attorney's possession separate from the

attorney's own property. Funds shall be kept in a separate account maintained

in the state where the attorney's office is situated, or elsewhere with the consent

of the client or third person. Other property shall be identified as such and

appropriately safeguarded. Complete records of such account funds and other

property shall be kept by the attorney and shall be preserved for a period of

seven years after termination of the representation.

(b) Upon receiving funds or other property in which a client or third person has

an interest, a lawyer shall, promptly or otherwise as permitted by law or by

agreement with the client, deliver to the client or third person any funds or

other property that the client or third person is entitled to receive and, upon

request by the client or third person, render a full accounting regarding such

property.

(c) When in the course of representation a lawyer is in possession of property in

which both the lawyer and another person claim interests, the property shall be

kept separate by the lawyer until there is an accounting a nd severance of their

interests. If a dispute arises concerning their respective interests, the portion in

dispute shall be kept separate by the lawyer until the dispute is resolved.

(d) "Accounts" as used in paragraph (a) above shall mean one or more

identifiable interest-bearing, insured depository accounts; provided, that with

the consent of the client or third person whose funds are in the account, an

account maintained under subparagraph (e)(1) below (interest is paid to the

client or third person) need not be an insured depository account, but all

accounts maintained under subparagraph (e)(2) below (interest is paid to the

Colorado Lawyer Trust Account Foundation) shall be insured depository

accounts. For the purpose of this rule, "insured depository accounts" shall

mean government insured accounts at a regulated financial institution, on which

withdrawals or transfers can be made on demand, subject only to any notice

period which the institution is required to reserve by law or regulation.

(e)

(1) Except as may be prescribed by subparagraph (2) below, interest

earned on accounts in which the funds are deposited (less any deduction

for service charges or fees of the depository institution) shall belong to

the clients or third persons whose funds have been so deposited; and the

lawyer or law firm shall have no right or claim to such interest.

(2) If not held in accounts with the interest paid to clients or third

persons as provided in (e)(1), a lawyer or law firm shall establish a pooled

interest-bearing insured depository account for funds of clients or third

Copyright Robert R. Keatinge 2016, all rights reserved.

persons which are nominal in amount or are expected to be held for a

short period of time in compliance with the following provisions:

(a) No interest from such an account shall be made available to a

lawyer or law firm.

(b) The account shall include funds of clients or third persons

which are nominal in amount or are expected to be held for a short

period of time.

(c) Lawyers or law firms depositing funds in an interest-bearing

insured depository account under this subparagraph (e)(2) shall

direct the depository institution:

(i) To remit interest, net any service charges or fees, as

computed in accordance with institution's standard

accounting practice, at least quarterly, to the Colorado

Lawyer Trust Account Foundation; and

(ii) To transmit with each remittance to the Colorado

Lawyer Trust Account Foundation a statement showing the

name of the lawyer or law firm on whose account the

remittance is sent and the rate of interest applied.

The provisions of this subparagraph (e)(2) shall not apply in those

instances where it is not feasible to establish a trust account for the

benefit of the Colorado Lawyer Trust Account Foundation for reasons

beyond the control of the lawyer or law firm, such as the

unavailability of a financial institution in the community which offers

such an account.

(3) Information necessary to determine compliance or justifiable reason for

non-compliance with subparagraph (e)(2) shall be included in the annual

attorney registration statement. The Colorado Lawyer Trust Account

Foundation shall assist the court in determining whether lawyers or law

firms have complied in establishing the trust account required under

subparagraph (e)(2). If it appears that a lawyer or law firm ha s not complied

where it is feasible to do so, the matter may be referred to the disciplinary

counsel for investigation and proceedings in accordance with C.R.C.P. 241.

(f) Required Bank Accounts. Every attorney in private practice in this state shall

maintain in a financial institution doing business in Colorado, in the attorney's own

name, or in the name of a partnership of attorneys, or in the name of the

professional corporation or limited liability corporation of which the attorney is a

member, or in the name of the attorney or entity by whom employed:

(1) A trust account or accounts, separate from any business and personal

accounts and from any fiduciary accounts that the attorney may maintain as

executor, guardian, trustee, or receiver, or in any oth er fiduciary capacity,

into which trust account or accounts funds entrusted to the attorney's care

and any advance payment of fees that has not been earned shall be deposited

(except that such a trust account shall not be required if the attorney does

not ever receive such funds); and,

2

(2) A business account into which all funds received for professional services

shall be deposited.