Decentralization and Local Governance in the Context of China's

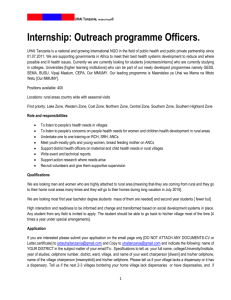

advertisement