The Determinants of Trade

advertisement

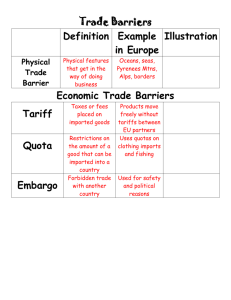

Topic 3B: Extremely Competitive Open Markets LECTURE NOTES International trade (the exchange of goods and services between countries) is rooted in microeconomics because it involves the demand, production and sale of goods and services in specific industries in which the exporting/importing countries may have a distinct advantage or disadvantage but it also has macroeconomic implications because it can affect a country’s level of employment, inflation, exchange rate and other macroeconomic variables. The idea behind international trade is the same as the idea behind trade in a closed economy: you’re better at baking bread than I am so I buy bread from you. I’m better at fixing appliances than you are so you pay me to fix your refrigerator. There are advantages to both of us from this type of exchange. In a closed economy the bread and refrigerators as well as the services related to them are manufactured and provided exclusively within the country. International trade involves opening up this type of exchange across countries. The Determinants of Trade The costs and benefits from trade are analyzed by comparing the market outcomes with and without trade, including the market-clearing price and quantity, on domestic and foreign consumers, producers and governments. This type of analysis helps us identify who are the winners and losers from increased trade or restrictions to trade. Understanding these underpinnings of international trade is extremely important for firms pursuing business strategies in competitive world markets Power Point Presentation “International Trade” In a strict economic sense, trade makes both exporting and importing countries better off in that overall welfare (consumer + producer surplus) increases. It may also have additional benefits in that it may contribute to increased economies of scale, competition, efficiency and exchange of technologies and ideas. But, in the case of exporting countries (world price > domestic price) consumers are worse off and producers are better off whereas in the case of importing countries (world price < domestic price), consumers are better off and producers are worse off. The total economic well-being of the nation is improved because the gains of the winners exceed the losses of the losers. But, because there are losers there is discontent associated with trade resulting in trade restrictions, disagreements and controversies. Question: From where does the main opposition to trade tend to emanate? Answer: When the world price < domestic price imports increase and producers are worse off (although consumers are better off). Even though the overall losses to producers are less than the gains to consumers, producers tend to be more concentrated, more knowledgeable and better organized than consumers and therefore to have a stronger say in opposing free trade when this results in losses to them. Therefore, they have a strong incentive to lobby for trade restrictions. Trade Restrictions: Tariffs Quotas Subsidies Other Trade Barriers: health or environmental-related regulations, regulations pertaining to quality, packaging, delivery requirements, etc. Overall arguments for trade restrictions: Protect domestic producers/jobs from competition National security Infant Industry Unfair competition Protection as a bargaining chip Macroeconomic stability Environmental/health and human rights considerations 1. Protection of domestic producers/jobs: Per se, this argument does not have much popularity among economists. A country should concentrate on those sectors in which it has a comparative advantage. This will result in a better use of the country’s resources and lower prices and more variety for consumers. If the US is really not as efficient at producing steel or textiles as Korea or China but is a lot more efficient at producing telecom infrastucture and television programs then it should produce less of the former and more of the latter. Nonetheless, this is one of the strongest arguments made for protectionist policies. If French residents do not buy foreign goods they will spend the money at home, creating more jobs for French residents. Again, an economist’s response to this argument is that in the end it protects no one and may end up instead reducing the overall standard of living of the country as well as of other countries. Opposing trade so as to protect domestic jobs can lead to what are known as beggar-they-neighbor policies in that the jobs gained in one country are at the expense of jobs in another country. But in fact, this policy often ends up reducing jobs even in the country implementing the policy. If the French impose very high tariffs on imports so that French consumers purchase French products for the most part, this may protect French jobs (compared to the alternative) for a while but it will also have two other negative effects: (1) the prices of those products may be significantly higher than in the absence of protectionism (which harms French consumers); and (2) there will fewer exports of products from France to other countries both because the other countries may retaliate and because France has not concentrated on producing products in which it has a comparative advantage. The result will be a reduction of French income and jobs from exports. Economists believe that one of the worst cases of this type of policy occurred during the Great Depression, when the US passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act raising tariffs on many products to levels which made imports unattractive. Imports to the US declined. This led to declines in incomes in other countries that used to export to the US. They in turn purchased fewer goods from the US and themselves imposed retaliatory tariffs. This resulted in declines in US exports and incomes and so forth. The result contributed, experts believe, to making the Depression particularly severe and deep and had a “contagion” effect which affected many different countries worldwide. Of course, it is important to realize that allowing the importing of goods and services from more efficient producers outside the country will result in a loss of revenue for some sectors. This may involve significant hardship for those industries. The government may then decide to ease these hardships e.g. by providing training to displaced workers, low interest loans, tax credits to On the other hand, the loss of jobs (or reduction in wages to be more competitive with cheaper imports) is a real hardship. Rather than protecting those jobs by imposing trade restrictions, the government could ease the effect on the labor market by passing laws that offer special assistance and training to displaced workers, low interest loans, special extended unemployment insurance provisions, tax credits to industry to shift production to an sector of greater comparative advantage, etc. Of course, how well and quickly this works depends on many factors, including the unemployment rate in the country, the age of the workers, the mobility of the workers, and even the efficiency of capital markets, etc. Unfortunately, trade liberalization often affects workers that do not have otherwise marketable skills outside their industry or are already among the poorest in the country. For example: US textile workers or Central American coffee farmers. Thus, the hardship can be extreme. Economists can comment only on the benefits of trade liberalization overall and over time, i.e. that the increase in surplus to the winners is greater than the decrease in surplus to the losers. This ignores the distributional effects (between winners and losers) and other repercussions not acknowledged in the standard economic analysis. For example, in countries with high rates of unemployment, international trade which results in job losses (opening country up to cheap imports, lifting tariffs and quotas or subsidies) does not result in an eventual shift of workers from the displaced sector to another sector but, more likely, to prolonged unemployment. The result then of trade liberalization may be more serious macroeconomic effects, such as increases in the poverty rate, infant mortality rate and declines in life expectancy (See Stiglitz, Globalization and Its Discontent, chapters 3, 5). In this case, there may really be no way for the winners to compensate the losers, even over time (unless you go to the next generation.) 2. National security: Some sectors are too sensitive for defense/national security reasons to be opened up to trade. 3. Infant Industry Protection: The rationale here is that new industries (or industries that are not necessarily new worldwide but are new in a given country) need temporary protection from worldwide competition in order to grow. As Mankiw points out, economists generally are skeptical about the logic of such arguments in that they essentially protect less efficient industries (on a worldwide scale of efficiency). If those industries indeed showed the potential for new breakthroughs, new products, lower costs etc., then they should be able to attract capital without protection. But that argument ignores a number of countervailing factors: (1) certain industries may not have adequate access to capital markets for a number of reasons, ranging from nepotism and corruption in the banking industry to risk aversion and lack of transparency in domestic financial markets; (2) certain countries may believe that it is in their best long-term interest for its labor force to invest in some “learningby-doing” so that the labor force becomes more knowledgeable and less reliant on foreign know-how (e.g. software in Mexico.) 4. Unfair competition/fair trade whereby the government of a trading country subsidizes some industry or product in that country-- for example, by giving it significant tax breaks. The domestic (nonsubsidized) producers of the product might argue that they should be protected against this “unfair” competition.” This is a very serious trade issue and one that is the focus of both the WTO’s mandate to uphold international trade law as well as standards and conditions imposed by the EU to its member countries. For example, the EU recently ruled that Spanish subsidies to the shipbuilding industry had not only to be eliminated but in large portion reimbursed to the Spanish government over a number of years. In the US, Boeing has for years vehemently complained about “unfair subsidies” granted to its competitor Airbus from the UK and French governments. (On the other hand, Boeing may itself receive some form of subsidy from the US government in the form of defense contracts.) To ensure fair competition, economists argue that the same laws that apply domestically should apply internationally between trading partners. Another law that is often resorted to in the name of “fair trade” is the anti-dumping law. Dumping refers to the sale of products to another country at a price below the producing country’s cost of production (predatory). If a country is found guilty of dumping, a tariff will be imposed on the price of its goods equal to the difference between the export price and the cost of production. However, according to Stiglitz (Principles of Economics, p. 368), the antidumping laws are most often used (abused) as a protectionist rather than fair trade tool. The standard for measuring the cost of production is based on what it would cost to produce the good in a “comparable or surrogate country”. Often the way this is calculated is ridiculous or erroneous. See example of aluminum in Russia (Globalization and Its Discontent, p. 173). 5. Protection as a Bargaining Chip Argument whereby the threat of a trade restriction by one trading country can help remove a trade restriction imposed by another country. (It also may be used in bargaining with regard to non trade issues, such as human rights.) The WTO is now playing a big part in this type of bargaining. If a country is found to have improperly imposed trade restrictions against another member of the WTO, the latter can retaliate by itself imposing sanctions or other restrictions. Examples: In 2001, in response to US banana producers (Dole and Chiquita) complaints of European countries’ policy of favoring purchases of bananas from ex European colonies, the WTO found the EU was in violation of GATT and allowed the US to retaliate in the form of 100% tariffs imposed on many luxury goods imported from Europe (luxury leather goods and linens and specialty foods, i.e. Gucci bags, Hermes scarves and Roquefort cheese.) The EU conceded defeat and changed its policy and the US lifted the tariffs. In August of 2003, the WTO ruled that US tariffs on imported steel were illegal and allowed the EU to impose more than $2 billion in retaliatory tariffs on key US exports, including citrus fruits and juices, agricultural equipment and paper products. By the end of the year, the US lifted its steel tariffs. In 2002, the WTO ruled that the EU could impose $4 billion in penalties on the US because of tax breaks given to US companies that operate overseas, arguing that these amount to illegal export subsidies. 6. Macroeconomic Stability and Volatility Liberalization of trade can bring significant volatility to output, prices, jobs, etc. In particular, according to some economists, liberalization of financial services can have a destabilizing effect on macroeconomic stability. Complete liberalization of financial services results in the ability of “hot” money to flow very quickly in and out of a country. As it provides increased liquidity and access to capital when things are good, the opposite is true when things are bad. Furthermore, large foreign banks may be less interested in lending to a country’s local businesses, preferring to lend to large multinational corporations. They will also be less susceptible to government pressure to lend during an economic downturn or to contract lending when the economy is overheated. “In developing countries, this ‘guidance’ from the government may be an important tool for macroeconomic stability” (Stiglitz, Principles, p. 375). For example, China’s government has been liberalizing capital markets very gradually, with capital controls still in place in certain sectors. This policy of capital controls ensured that capital did not swiftly flow out of China during the Sars epidemic scare. Economies with more developed capital markets are better able to hedge against volatility resulting from trade liberalization. There are important differences in the ability to manage risk between developed and developing countries and, therefore, that there is an asymmetry in the effects of liberalizing trade in developed versus developing countries. However, given the current serious crisis in financial markets of developed countries, we may need to question the ability of developed market economies to deal with financial market liberalization and, generally, with the effects of globalization. Class discussion. 7. Environmental, Health and Human Rights Considerations There are environmental and health considerations associated with international trade which are not specifically elements of the trade itself but rather of underlying rules and regulations specific to the countries engaging in trade. Thus, a country may decide not to import goods and services which it believes do not meet its own health, environmental standards or rather to require that all imports all meet those standards. Examples include: food products with growth hormones, Genetically Modified Foods (GMOs), inadequate labeling of contents, unsanitary packaging facilities, excessive pollution emissions. Also, some countries may decide not to trade with other countries where working conditions are significantly inadequate (child labor, excessive hours, extremely low pay, unsanitary working conditions) or human rights violations are a serious concern. READINGS 1. How to Fight Currency Wars with a Stubborn China, Financial Times,October 6, 2010. http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2248/lnacui2api/api/version1/getDocCui?lni=515R-RT81-JBFSD154&csi=293847&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=00240&perma=true 2. Free of Quota, China Textiles Flood the US, The New York Times, March 10, 2005. http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2248/lnacui2api/api/version1/getDocCui?lni=4FNM-CWS0TW8F-G2RY&csi=6742&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=00240&perma=true 3. Battle is Looming Over Cotton Subsidies, The New York Times, January 24, 2004. http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2248/lnacui2api/api/version1/getDocCui?lni=4BHY-HMR001KN-23D5&csi=6742&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=00240&perma=true 4. Sugar Subsidy Reform: A Bittersweet Story, Emerging Markets Monitor, July 4, 2005, Vol. 11, Issue 13, p. 21. NEW LINK—click on PDF Full Text http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2262/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=17526802&site=eho st-live 5. U.S. Loses Appeal on Steel Tariffs; WTO Decision Lets EU Retaliate, Washington Post, Nov. 11, 2003. http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2248/lnacui2api/api/version1/getDocCui?lni=4B06-M790TW87-N2KB&csi=237924&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=00240&perma=true 6. U.S. Slaps Sanctions on EU in Banana War’s First Strike; Clearance Withheld on Imports from France, Italy and Britain, The Globe and Mail, March 4, 1999. http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2248/lnacui2api/api/version1/getDocCui?lni=4M8C-DTJ0TW7J-32M4&csi=237924&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=00240&perma=true 7. The Airbus-Boeing Dispute: Implications of the WTO Boeing Decision, Intereconomics,Vol. 45, Issue 5, September 2010.NEW LINK—click on PDF Full Text http://www.biblio.liuc.it:2262/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=54371982&site=eho st-live 8. “Why the Oil Price is Falling,” The Economist, December 8, 2014. http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2014/12/economist-explains-4 SAMPLE PROBLEMS 1. International Trade: Tariffs versus Quotas In the late 1970s, the US government agreed to allow importing of fuel efficient compact cars into the US. In doing so, it considered the following two proposals: (1) Allow imports of Japanese cars into the US but subject to a 20% tariff. (2) Allow a limited quota of Japanese cars to be imported. The quota amounts would be allocated in equal amounts to Toyota and Honda with no license fees. For simplicity, assume the impact of the quota on price is equivalent to the tariff, i.e., it results in a US price for the Japanese cars with the quota equal to the unrestricted world price + 20% tariff. a. If you were the chief operating officer of Toyota, which of these two trade proposals would you prefer and why? b. If you were an economic adviser to the US president, which of these two trade proposals would you prefer and why? Answer: a. I would prefer the quota proposal for two reasons: (1) The quotas would be granted exclusively to Toyota and one other competitor, Honda. Under the tariff system, any producer of fuel efficient cars could export them into the US and therefore, Toyota would face a lot more competition for its sales. (2) Under both the quota system with no license fees as under the tariff, the domestic (US) price of the imported cars will be higher than the world price, as shown in the graph below. However, under the quota system with no license fees, this results in profits for holders of the import licenses. The profit derives from being able to sell the cars at the higher US domestic price associated with the imposition of the quota (Pq) compared to the lower world price Pw. It is equal to the area (Pq – Pw) * (Qd(Pq) – Qs(Pq)). Since we are assuming that Pw + t = Pq, this same area is revenue to the US government under the tariff system. See graph below. $/car Domestic supply Domestic supply + quota Pw+t= Pq Pw Domestic demand Qs(Pw) Qs(Pq) Qd(Pd) Qd(Pw) Fuel efficient compact cars/month b. I would prefer the tariff proposal for many of the same reasons that Toyota and Honda would prefer the quota system. Specifically: (1) The quota system results in less competition in the market for fuel efficient cars exported into the US. (2) It also incentivizes a system of lobbying by Japanese car companies to the US government to be granted the import license quota. (3) Finally, without a charge for the license fee, it results in no revenue for the US government (and its taxpayers) compared to the tariff. Under a tariff system, the area of profit to the license holders is tariff revenue to the US government. Some students may suggest that the government may prefer the quota because it gives it some negotiating leverage with Japan (bargaining chip) on this and other matters. 2. Arguments for Restricting Trade Explain how the “jobs protection argument” for restricting trade leads to hypocritical positions on trade. Answer: The jobs argument would lead countries whose domestic equilibrium price in certain industries is lower than the world price (i.e. exporters) to be in favor of free trade so as to promote domestic jobs in those industries. The opposite would occur in the case of countries whose domestic equilibrium price in certain industries was higher than the world price (i.e. importers). They would oppose free trade and promote restrictions on trade in those industries in order to protect domestic jobs in those industries. Note that the same country can therefore take positions for and against trade restrictions across different industries. For example, the US is a strong proponent of free unrestricted trade in financial and telecommunications services but imposes significant trade restrictions (import tariffs, quotas and domestic subsidies) in textiles and certain agricultural crops. 3. Production Subsidies Suppose the domestic demand and domestic supply for wheat in Algeria is characterized by the following functions. Qd = 1500 – 5P Qs = -1100 + 5P Where P is in Algerian dinars and Q is in thousands of bushels per year. Algeria is a small economy relative to the world demand and supply of wheat. a. Find the market equilibrium price and quantity for wheat in Algeria under autarky (no trade). Show these on a graph. Calculate producer revenues and consumer expenditures. b. Suppose the world price for wheat is 240 dinars/bushel. If Algeria opens up to trade, will it be a net importer or exporter of wheat? What will be the prevailing price of wheat in Algeria? How much will Algeria produce domestically and how much will it import/export? Show this outcome graphically. Calculate the effect on domestic producer revenues and consumer expenditures from Algeria’s opening itself up to international trade in the market for wheat? Algerian wheat farmers are outraged at their loss in revenue due to the lower world price. They lobby the Algerian government for intervention on their behalf. The Algerian government elects to give farmers a production subsidy of 10 dinars/bushel. c. What price will consumers face and how much will they consume under the subsidy? How many bushels of wheat will Algerian farmers produce? How many bushels will be imported? Show this outcome graphically (in a separate graph or on the one you provided in (b) above.) Calculate producer revenues and consumer expenditures. How much will these subsidies cost the Algerian government? Answer: a. Qd = Qs 1500 – 5P = -1100 + 5P 2600 = 10P P* = 260 dinars/bushel Qd = 1500 – 5(260) = 200 Q* = 200 thousand bushels/year Producer revenues = 260*200,000 = 52,000,000 dinars/year Consumer expenditures = 260*200,000 = 52,000,000 dinars/year Dinars/ bushel 300 P*=260 Pw=240 220 Thousands bushels/year 100 200 300 Imports 1500 b. Algeria will be a net importer of wheat. The prevailing price will be the world price, 240 dinars/bushel. Qs= -1100 + 5(240) = 100 thousand = 100,000 bushels/year Qd = 1500 – 5(240) = 300 thousand = 300,000 bushels/year Imports = 300 – 100 = 200 thousand = 200,000 bushels/year Producer revenues = 240 * 100,000= 24,000,000 dinars/year Consumer expenditures = 240 * 300,000 = 72,000,000 dinars/year c. Consumers will still pay 240 dinars per bushel, as before. The imposition of the production subsidy does not affect the world price paid by consumers. Thus, the quantity they consume (300,000 bushels/year) also remains unchanged. With the production subsidy producers receive world price + subsidy, i.e. 240 + 10 = 250 Thus, producers will supply: Qs = -1100 + 5(250) = 150 thousand = 150,000 bushels/year Qd = same as before = 300 thousand = 300,000 bushels/year Imports = Qd – Qs = 300 – 150 = 150 thousand = 150,000 bushels/year Producer revenues = 250 * 150,000 = 37,500,000 dinars/year Consumer expenditures = same as before = 72,000,000 dinars/year Cost to government = 10 * 150,000 = 1,500,000 dinars/year Dinars/ bushel 300 P*=260 Ps=250 Pw=240 220 Thousands bushels/year 100 150 200 300 Imports 1500