Chapter 7

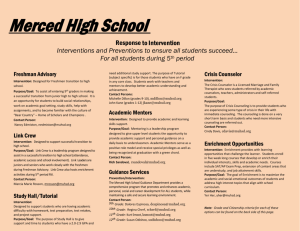

advertisement

Restitution in Greece i. The clause-a secondary action? The general clause of Art. 904CC provides that ‘every one who was unjustly1 at another’s expense or though another’s estate is obliged to return the enrichment. This obligation exists especially in the cases of a performance not due or a performance for a cause which did not continue, or a cause which ended, was illegal or immoral.’ The obligation for the return of unjust enrichment is a general and an ex lege obligation, a personal obligation stemming directly from the law. In this sense, in Greece, unlike many other countries, unjust enrichment is the third most important source of (all) obligations2. Restitution is, therefore, necessitated, because of the need to conform to iustitia commutativa, commutative justice. The prevailing opinion in Greece supports, despite the strong disagreement of legal theory, that the claim for unjust enrichment is valid only when no other claim exists to offer relief, for the particular set of facts. The letter of the clause does not justify this view; it is much more not justified by the purpose of the institution. Art. 904CC does not include the non-availability of another cause of action into its conditions; every rule of law is applicable once its conditions have all been fulfilled. Perhaps that another cause of action exists has a consequence that the Art. 904CC conditions are not fulfilled; for example, when a valid contract exists, and one of the parties has not performed, the other party who did perform first is not unjustly enriched by accepting the performance, because the enrichment is justified as coming from a valid contract. But this is not an effect of the supposed supplementary nature of unjust enrichment; it is a consequence of the lack of enrichment, which is unjustified. Even in common law, where there is no such thing as a general clause of the prohibition of unjust enrichment, as a cause of action in its own independent right, the plaintiff is always allowed to waive a tort and sue in unjust enrichment, if she so wishes (usually, when the return of the enrichment from the tort is more favorable I should translate ‘unjustifiably’, in fact, but as the law of restitution always refers to unjust enrichment, and not unjustified, meaning the same, I preferred the usual term of art in this case. 1 than damages for tortious losses). Another matter, which is in doubt, is whether the directness of the transfer of the benefit (only between A and B) is also a (non-written, again) condition of the claim. As there is nothing in the article on this particular matter, this opinion should not be followed. ii. Unjust enrichment-civil law, public law, common law Unjust enrichment, no matter how closely related to contracts it may be, is not just a means to achieve the reverse development of a failed contractual relationship (‘give me back the money, I will give you back the product’), although many times it is; nor is unjust enrichment another remedy to compensate for tortious losses (‘give me the profits from the illegal use of my patent’), although, again, many times it is. The law of unjust enrichment is more vague and distant from the more concrete breach of contract, or tort cases: it orders the return of an unjustly gained enrichment to the proper party-no more, but certainly no less, than this. Because of this general nature, we see unjust enrichment invoked not only in sets of very different circumstances (from the classic return of money paid under a contract which was terminated, to the return of gains immorally made, though another persons’ labor etc), but also, in different laws: both in private and in public law (that is, a suit for the return of a quashed fine by a public authority, will also be based in unjust enrichment). Jurisprudence has accepted this clear surpass of the clause and its application in public law relationships, after a period of doubt 3; today, a great number of cases from the administrative courts accept that the rule against unjust enrichment exits and bears legal consequences in public law too4. 2 Stathopoulos, The Claim for Unjust Enrichment, 1972, the classic wonderful monograph on the subject, p. 28. 3 Stathopoulos, Law of Obligations, 1998, 317. 4 Pavlopoulos, Unjust Enrichment in Public Law, at the Border of the Relations of Public and Private law, NoB 1998, 2, p. 10. Pavlopoulos attempts to prove that the material disputes of administrative law dictate other kinds of legal solutions than unjust enrichment and restitution. It is, however, better to accept unjust enrichment as a cross-laws clause, since there is no reason to support that an administrative authority, which had mistakenly imposed a fine, should be treated differently from a private party, who received an undue debt. The set of facts is the same: the mistaken transfer of a benefit, necessitating its return. Unjust enrichment situations are not influenced from the fact that one of the parties is a public person, even when acting as a public person (exercising public authority); if this is so, the public person has the burden to prove why it deserves a special treatment (in this case, Stathopoulos, id, proposes the application of Art. 904CC by analogy). I believe that it is very comforting, in a perplex system of laws, to accept and apply some general principles as Art. 904CC in every situation where it is just, and no other special regulation may help a litigant. One may only remember the days in Greece when not even the competence of civil and administrative courts was not From the comparative law point of view, restitution is never a substitutionary remedy, so that a plaintiff may ask for the restoration of money paid, for example, as a better choice from compensatory damages. Restitution is not an end (‘because of this-a breach of contract, a tort, other causative event etc, I ask for restitution’), but the beginning (‘because you were unjustly enriched etc, I ask for the return of the enrichment’). Restitution, therefore is not a legal consequence of a breach of contract or a tort, it is not an ‘option’, as a preferable measure of damages; the plaintiff is not allowed, not explicitly at least, to waive the tort5 and sue for restitution. Unjust enrichment is a cause of action in its own right; one of the three main grounds of damages in the law of obligations. There is absolutely no need to stress in Greece, as there is in the common law, that there is an unjust enrichment policy behind all restitutionary actions6, for in Greece, because of Art. 904CC, we need no reference to policy. Quite apart from this important difference, the focus is the same in our law and in common law: the law forces a party to disgorge the gains-actions for restitution have for their primary purpose taking from the defendant and restoring to the plaintiff something to which the plaintiff is entitled, or if this is not done, causing the defendant to pay an amount which will restore the plaintiff to the position he was before the defendant received the benefit. This principle, the main theme of the American Restatement of Restitution, because I did no more than copying it from the Restatement, could be easily written in the Introduction to the law of unjust enrichment, written by a Greek scholar. And it is very interesting to compare the six major counts of the claims for restitution, as they were established in the pleading forms of the common law (actions for money had and received, money paid for the benefit of the defendant, goods sold and delivered, work and labor performedquantum meruit- and value of the product-quantum valebat), to the Roman sharply defined, and how a statute, many years after cases were systematically thrown out of both courts, one after the other, for lack of competence, came to remedy the matter. Looking at the system from a big distance and under the light of equity and stability supports the direct application of the clause of Art. 904CC in whatever law it may apply. Besides, ‘..finally, law and order form one entity. And it is a legal reality, that the Civil Code as an old and general law, contains rules surpassing the limits of civil law, in which is possible to co-estimate matters of public interest…’, Stathopoulos, Law of Obligations, 1998, 318. 5 As a standard rule, in common law, whenever a tortfeasor wrongfully takes, uses, withholds or disposes of the property of another, the victim has an action for conversion-however, as a plaintiff, he also has the option of waiving that tort and suing in assumpsit (today, in unjust enrichment) to prevent the unjust enrichment of the defendant tortfeasor. Of course, the only case where this is a good idea, is when the defendant’s gains are to be reached condictiones, for unjust enrichment, as they are still sometimes cited in the Greek law: action (the Roman condictio) for a cause which did not continue (condictio causa data causa non secuta), for the return of a mistakenly paid debt (condictio indebiti), for the return in the case where there was no cause (condictio sine causa), for the return in the case where the cause was unjust (condictio ob turpem vel iniustam causam), for money for services rendered (posse condici, quandi operas essem conducturus) etc. Such a comparative analysis, in detail, would reveal that it is the same sets of facts, which leads to the application of the rule of the return of unjust enrichment, somehow differently classified, but still the same. What is certain is that, while in England, at least, and with some reservation, also in the US, the principle of restitution has not yet formed a clear part of the law7, in its own right, there are some tendencies towards this direction. We see, though, in the American textbooks, ‘restitution’ (this is the central point, and not ‘unjust enrichment’) analyzed as a part of the law of remedies as a remedy for a tort/wrong (especially for duress, unconscionability, undue influence etc), for a contract (for example, for a vendee’s breach, for a contractor’s breach, for breach by employee, for all unenforceable contracts etc)-we do not see restitution, as a remedy for (all the whatever cases of) unjust enrichment. This is, however, the case in Greece. In continental Europe, the principle against unjust enrichment is good law, and is based upon a. enrichment b. another’s expense/loss and c. no justification, conditions which sustain a claim for the return of the benefit. I turn now to the analysis of these conditions. iv. What is ‘enrichment’-when is an enrichment at another’s expense, or though another’s estate The law of unjust enrichment aims at the return of a financial benefit, and not at the return of a specific thing or money. What is important is not the economic value, embodied in an object, but an estate in its general state. The institution covers property increases and decreases of any nature whatsoever, and not only those effectuated with the transport of a particular thing. Even when the enrichment was the result of the use of benefits, which do not have a physical and tangible existence (use 6 O’Connel, Remedies, 1985, 76. of another’s labor etc.), in all these cases, what is finally critical is the value, as a financial magnitude, of these benefits. Enrichment is every amelioration of a person’s the status of property. The court will not focus only on the particular acquisition, but on the comparison between the property status before and after this acquisition. So, a person may have acquired ownership or possession of a thing, may have acquired a claim or another right (even a formative right, or an expectation right), with the reservation that what was acquired, had a financial value. The enrichment is not confined, though, to the ‘prison’ of rights (I include here the acquisition of things, because it is the right to a thing which is legally valuable, and not the thing itself); a beneficial legal or real status, as the acquisition of clientele, also comes under the definition of ‘enrichment’. The release from an obligation (for example, the valid payment of another’s debt) is also an enrichment. The avoidance of costs forms a large class of Art. 904CC actions; for example, the use or consumption of a thing belonging to another, the exploitation of another’s work, the use of another’s right or thing etc. But the avoidance of costs has to be real, in the sense that the defendant would incur the costs claimed as unjust enrichment. This is a question of fact. Lack of legal cause. The benefit claimed must have occurred without a legal cause, which would justify its remaining with the defendant. Cause here is much more general, as a concept, than causal connection we see in the classic tort cases. A cause is a fact, which in itself justifies the final keeping of a benefit. The sources of this justification are three: a. the donor’s will (a gift; a contract of sale, and the relative performances etc) b. consideration offered in return of a benefit and c. the law (in some cases, the law designates some benefits as just). ‘Moral’ benefits, intangible and imposed enrichment. Unjust enrichment is an institution primarily dealing with the return of benefits having a financial value, to the degree that this value is subject to measurement. Other ‘moral’ goods, as, for example, health, freedom, amusement etc are not subject to a claim for unjust enrichment-there are other Civil Code provisions, more suitable for the relevant claims8. One should not confuse, though, the concept of the return of purely moral benefits, unjustly acquired, with the concept of ‘intangible’ enrichment, as is, for example, the enrichment of the use of another person’s services. The enrichment does 7 The Restatement contains general guidelines and not rules of law. Stathopoulos in ErmAK, Art. 904CC, 4, who nevertheless, leaves the door open for the application by analogy of Art. 904CC for a claim of the return of these moral benefits. 8 not have to be tangible in any way; intangible benefits have a financial value, when they represent, for example, the saving of costs. Crucial is, however, the enrichment, which was real and concrete, not the enrichment that a person was able to obtain but failed to do so. Acquisitions, which offer a real, financial opportunity to gain, are crucial, and not those, which could represent a financial gain, purely theoretically. The matter of ‘imposed’ enrichment, which is the enrichment allegedly, imposed upon an innocent party, by an officious intermeddler, is not easy to resolve. The rule remains, of course, that an enrichment not sustained by a legal cause, a just cause, in principle should sustain the claim. The focus is whether the defendant was enriched, because in many cases, the claim will be defeated, not because the enrichment was imposed, but because it did not exist at all: the alleged saved costs, for example, were not costs that the defendant would incur anyway, etc. The lack of enrichment invalidates the claims. The judge, though, should have the discretion to impose upon the enriched party the obligation to a sacrifice analogous to the meaning of the benefit received, using as compass the mission of the institution of unjust enrichment9. A last note here is, though, that in cases where the court orders the return of an ‘imposed’ enrichment, an enrichment to which the plaintiff had never consented to in any way, the court should, I believe, take into account other interests harmed with the imposition of the enrichment, apart from the purely and objectively monetary ones. By this abstract statement I mean that, if, for example, I build a house upon your land and then sue you for your ‘imposed’ enrichment, what I, as a person and a free citizen of this State, wanted to do with my land, cannot be irrelevant to the action. Perhaps you built a house at a style, which I absolutely hate; perhaps you built a swimming pool, but I cannot swim; perhaps I never wanted to build a house there anyway, but a golf club. So, this is a clear case where the real and the unwanted amelioration of another’s property clash10. One way to resolve this is, as above, to claim that this is not an enrichment. In some cases, though (suppose one built an absolutely wonderful house, definitely ameliorating the land in money terms) it would be irrational to claim that there was no enrichment (objectively). Another, conceptually better, I believe, way, is to balance the true amelioration of the plaintiff’s financial status with the harm to the plaintiff’s 9 Stathopoulos, id., 16. Kotzabasi, The Claim for Unjust Enrichment in the Cases where the Enrichment is Imposed, without the Recipient’s Consent, Nomos, Scientific Yearbook of Athens Law School, ar. 4, p. 309 311. 10 interests in freedom of choice-specifically of the choice what to do with her own property (balance of the injury to personality, because of the injury to choice, under Art. 57CC11 and promotion of financial status). The very word ‘imposed’ enrichment, as a term stabilized in the law of unjust enrichment, embodies the undisputable fact that a person’s freedom was violated, as the Constitution protects individual means and possibilities of all people, as their own12. Perhaps, this dimension of the problem should not be overlooked. One thing is certain: the judge in these cases, after the examination of the facts of the case, should have the discretion to tailor the award, using as tools the general principles of civil law-the principle of good faith, the prohibition of the abuse of rights etc. And the degree of the defendant’s fault here, contrary to the usual rule (irrelevant), is certainly a factor determining the quantum of liability in ‘imposed’ enrichment cases. This would conform to the overall mission of the institution of unjust enrichment, to the demands of commutative justice. v. ‘Surviving’ enrichment A usual defense to the claim of unjust enrichment is that the defendant does not ‘have’ the enrichment any more, at the time when the claim was filed. The defense is based on Art. 909CC, which states that the enrichment may be claimed, only if, and in so far as, it exists, as it was, or under the form of a benefit given in return for the enrichment, which benefit replaced the initial enrichment. This peculiar, at the first sight, rule, is however justified, as the lawmaker wishes to stress, that it is not the acquisition of enrichment that is crucial in these cases, but the enrichment itself13. Equity dictates that the recipient in good faith is no more liable to return an enrichment she did not know was unjust, after she is not any more enriched. The safety valve of the condition of good faith here ascertains the justice of the rule. An enrichment may not survive, not only in the cases where, for example, the money was spent, but also when the total estate of the recipient suffered a loss. An enrichment does not survive, when it is offered to a third party, as a gift (Art. 913CC). If the recipient did not receive anything in return for the enrichment 11 On freedom of choice and Art. 57CC (personality), see Canellopoulou-Bottis, Informed Consent Medical Liability in Greek and Common Law, 1999. 12 ‘…Even if a person did not want, or could not realize these means or possibilities (to gain financially), they still belong to her. Third parties intervening in this legal and financial sphere of influence, gain through another’s means..’, Stathopoulos, ErmAK, id., 20. given, and also did not save expenses, which she would have incurred (in this case, she is still ‘richer’, as she saved costs), then there is no enrichment to return. The recipient defendant is entitled to offset all costs incurred because of the acquisition and keeping of the enrichment: for example, the recipient defendant is entitled to deduct the costs of the maintenance of a house, or the extra costs of travel incurred, because, due to the enrichment, she believed she was richer and she was in the position to spend extra money for pleasure. vi. Cases of heavier liability of the recipient Articles 910-912CC provide for the cases where the recipient defendant is not offered the favorable protection described above, mainly because of the recipient’s state of mind, which allows for a different liability. So, after the claim is filed and notified, the recipient is fully responsible for the enrichment (Art. 910CC). Also, after the recipient learnt that the debt paid did not really exist, the recipient is liable for its return (Art. 9133, sec. 1). The provision means positive knowledge, and not culpable ignorance that the debt was not valid. If the cause of an enrichment was illegal or immoral, then the recipient is fully liable (under the general provisions of Art. 346 and 348CC). In this case, positive knowledge or culpable ignorance are irrelevant. If the claim was founded upon a cause, which did not ensue, or ended, the recipient is fully liable from the moment the recipient should have foreseen that the enrichment was returnable (Art. 912 sec. 1). The provision presupposes positive knowledge, or negligent ignorance of the recipient, that the enrichment could be claimed. Negligence will be judges objectively (would a reasonable person foresee the possibility of a claim). All the above rules embody the ratio that, a recipient in bad faith, that is a person who could or should diagnose that there is a chance that the enrichment received could be claimed, should treat the enrichment very carefully, as it it did not belong to her. It is also supported14 that these articles may be applied by analogy, in all cases where the same reasons (knowledge of lack of a legal cause to keep a benefit) dictate a heavier than usual liability for unjust enrichment. 13 14 Stathopoulos, ErmAK., id., Art. 909CC, 1. Stathopoulos, id., Art. 910-912, 6, Georgiadis, Law of Obligations, id., p. 573. The consequence of the above is that the survival, or not, of the enrichment is irrelevant to the claim for its return; that if the enrichment is money, interest is owed; if the enrichment is a thing, the recipient is liable for it deterioration etc, for all fruits of the thing, even those that the recipient could but did not collect; finally, the recipient’s right to an offset of costs incurred is severely limited. vii. Third parties as recipients from the original recipient Art. 913CC deals with the liability of a third party, which was the final recipient of an unjust enrichment. As the claim for unjust enrichment has a limited personal character, in the sense that the link is not restricted between the two original arties involved (as in contract cases, for example), the plaintiff may follow the enrichment even if it ‘ended’ up in the hands of a third party. The conditions, though, are somehow strict: a. that the original recipient is not liable for the return of the enrichment (prevailing opinion)15 and b. that the third party received the enrichment under a gratuitous transfer. If not, that is, if the third party paid, or offered consideration for the claimed enrichment, the action will fail. Gifts and inheritance fall within the term ‘gratuitous cause’ of the article. viii Cases The Athens Court of Appeals heard in 1987 a case of a public person, the Organism for the Public Schools Buildings, against a person who had used one of its plots of land as a parking lot, without any right whatsoever. He received money for the parking of around 270 cars every day. The Organism sued in unjust enrichment and asked, inter alia, for the return of the profits made through the use of its land. The Court held that, as the Organism did not have the legal ability to rent the place as a parking, because the legislation allowed the Organism to deal only with the erection of school buildings, there was no causal connection between the arbitrary use and the profits, so this claim failed; the Court allowed a claim for the rents the defendant would pay to the Organism, had he legally rented the place16. In 2001, the Supreme 15 There is a doubt, concerning this condition, as it is also supported that the claim is possible, even if the original recipient can be sued too. 16 AthensCA 2073/1987, HellDni 29 (1988), 550. Court held that in cases where the reversal of a sale is ordered, the return of the money paid under the contract will be claimed through the contractual cause of action, but any surplus, not mentioned in the text of the contract (‘black money’, to avoid tax) is returnable through unjust enrichment17. If any contract for work is invalid (because, for example, the worker did not issue a health booklet, as the law requires, or the alien worker did not have the permit to work in Greece), the worker may ask for the wages through the unjust enrichment clause18. After the prescription of a claim for the ejectment from a realty (one year), the plaintiff may ask for the restoring of the possession to him under Art. 904CC19. The plaintiff, in another recent case, sued for the value of a car ‘gained’ at a lottery by another member of the party, in which he had a number, which won, but was subsequently invalidated. The Court held that unjust enrichment was the proper cause of action, but agreed that the invalidation of the lottery ticket was legal and dismissed the claim on the merits20. In another case, in Thessalonica, the plaintiff, who lived for a number of years as a prostitute, sued her ex-boyfriend, with whom she had lived for a while and had a child from, to recover money paid to him by force, in exchange of ‘protection’. The man, who had promised to marry her, but was subsequently found to be already married to another woman, had extracted various amounts from the plaintiff, to buy realty (claiming that afterwards he would transfer it to their child, which never happened) and to buy antiques and ancient coins. The Court held that this reason is an immoral cause to keep a benefit, under Art. 904CC (citing older cases from the Supreme Court) and ordered the return of money paid. The Court, most notably, dismissed the claim that, since immorality ‘touched’ both parties, the money should not be returned21. In 2000, also, money paid to cover a cheque given, with the promise that the recipient would leave the place of an auction and not take part in it, was ordered to be returned under Art. 904CC22, as the ‘contract not to participate’ was held invalid, as against good morals (Art. 179CC). Other cases, where the lack of a formality invalidated a contract, were decided as unjust enrichment cases, in so far as they ordered the return of money paid under the 17 AP 524/1001, Nomos, 2002, 1. AthensCA 2976/2001, DEE, 2001, 1158; PireusCA 497/2000, D/ni 2001, 789. 19 AthensCA 352/2001, D/ni 2001, 809. 20 Rhodes OneMember DC 35/2001, Nomos. 21 ThessCA 810/2000, Harm 2001, 319. 22 LeukasOneMemberDC 178/2000, Nomos. 18 (invalidated) contract23. The sale in an auction of a realty, which had, however, become a thing of common use (‘κοινόχρηστο’) signified a legal defect of the thing auctioned and the buyer sues for the return of the money paid under Art. 904CC24. In many cases, the law itself states that benefits etc are returnable under the rules of unjust enrichment; such is the case of an engagement, which was annulled, and the gifts offered because of the engagement25. The Supreme Court dismisses a claim for money as wages, because the plaintiff used to go every day and help his ex-wife’s business (a business where more were partners), at times when she was not there, because the courts found that he had offered his services freely and with no expectation to be paid; besides, the business had its own employees for the same tasks, and did not need his services26. Generally, jurisprudence on unjust enrichment is really rich. A special matter is claims by persons who lived with other persons, but who were never married, for various reasons. These people are considered to live in a ‘free union’ (ελεύθερη ένωση). The problem occurs, of course, when the couple separates, or even, when one of the cohabitants dies. In one case in 1993, the Supreme Court27 held that the woman, after the man died, did not have any rights to his property, after 20 years of cohabitation. She had framed her case as a claim for services rendered, under Art. 904CC; the court held that there was no mutual understanding that something was owed for these services, that the man never treated the woman as his domestic helper, but had paid all necessary costs for their common living. The man’s heirs were allowed to the total of his inheritance; she was left with nothing. Another way to achieve some positive results for the women freely living with men was to invoke the application by analogy of Art. 1400CC, the article instituting a claim to a part of the acquisitions during a marriage. At least one court ahs dismissed this proposition, ruling that in the case of people freely living together, the only sustainable claim is the claim for unjust enrichment28; another court accepted the analogy29. The practical difference between the two claims is great: there is no need to prove the unjust nature of the enrichment, under Art. 1400CC, as there is under Art. 23 PireusCA 539/2000, Pireus Jurisprudence 2000, 343, sale of a vessel, written form not kept. AthensCA 436/2000, D/ni 2001, 1378. 25 AthensCA 2829/2000, Nomos. 26 AP 180/2000, Nomos, 2000, 1. 27 AP 351/1993, NoB 42, 998. 28 KozaniOneMemberDC 204/1999, NoB 48, 2000, 1446, comment by Efi Kounougeri Manoledaki. 29 RhodesOneMemberDC 206/1991, HellDni 36, 725. 24 904CC and the plaintiff is also burdened to prove how much of the estate was due to her own contribution (for Art. 1400CC, there is a presumption of contribution up to 1/3 of the net increase of the property). As usually people who live together, but are not married, do not wish that their partner is treated unjustly after they die, the courts should prefer in these cases the special rule of Art. 1400CC30. 30 See Kounougeri Manoledaki, id.