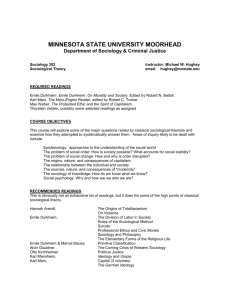

1) Classical Social Theory: The European

advertisement

The American University in Kyrgyzstan Department of Sociology Classical Social Theory: The European Tradition Instructor: Madeleine Reeves, CEP Visiting Lecturer Course Code: SOC 210 Class meets: Tu, Fri 1.00 pm Office hours: to be arranged Email: madeleinereeves@yahoo.com Phone: 66-10-92 (office) 66-26-48 (home) Course description How does society hang together, and why does it sometimes seem to fall apart? What are the possibilities and problems of the “modern” world: is it a world of increasing freedom, or one of increasing alienation, bureaucratisation and despair? How can we explain individual action and the social contexts in which all humans necessarily exist? Can we ever fully “get outside” our own world-view and examine it critically. How can we account for sudden and dramatic shifts in social and political structures? Do individuals make society, or does society make individuals? How do we make sense of the injustices we see in our world? How is it that some people have power over others? These questions, which motivate the social sciences, remain as challenging today as they ever were. This course examines some of the answers that were offered to these questions during a period of massive political, social and ideological change. We will look at the work of some of the most powerful and influential thinkers of the midnineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the answers they attempted to formulate to these questions. We will examine these authors both textually, by engaging with original texts (rather than simple potted summaries) and contextually, by looking at the social context in which they were writing and the impact this had upon their ideas. We will examine their agreements and their disagreements, as well as their impact upon social thought up to our own day. The aim of this course is four-fold: a) to introduce students to some of the key social thinkers, their theories, and the contexts in which they wrote; b) to enable students to engage with, comprehend and analyse complex and often challenging theoretical texts (and hopefully by the end to enjoy them too!); c) to help students to develop personal, critical responses to these texts and formulate these responses in a coherent, focused fashion; d) through that process, to help students to “think sociologically” - that is to make theory their own by linking the answers suggested by these classical texts to their own understanding of the social world. Assessment rationale The assessment will be based upon 3 basic elements: your degree of participation in the class, the quality of your answers to two in-class exams, and your response to 4 x 2-page AQCIs (these are explained below). In all cases, I am much more interested in seeing whether you have understood and are able to convey the ideas and arguments of the theorists whose work we will be reading, than to see whether you have memorised lots of random facts about them. Remember - this is ultimately a class about ideas and about the “big questions” which every thinking person asks themself, rather than about dates and numbers. 1. Attendance, participation and timeliness of work. It follows from the introduction given above that doing social theory is an active process, which involves reflecting upon and sharing personal experience of the social world, as much as reading what certain classical authors thought about it. Active class participation is therefore an essential part of this course and it will be assessed as part of your final grade (10%). Active class participation depends on critical, engaged reading of the text, and thoughtful writing of the AQCI responses. Questions, comments and interjections relating to the material covered are actively welcomed during lectures. Back-row discussions, sleeping during class and doing homework for other courses is definitely not!!! Students who are clearly not attempting to engage with the material or who consistently miss classes will be dropped from the course. Written work that is handed in late will likewise result in a penalty for this part of the grade. 2. Mid-term and final exams. These will be closed-book, in-class exams dealing with all of the material covered in the first half of the course, and the entire course respectively. The exams will consist of a mixture of short answer and essay-style questions. 3. AQCIs. An “AQCI” is a short (approx. two pages A4), structured and critical response to a particular text or texts which are set for that section of the course. Four of these AQCIs are due during the course of the term, to be handed in at the end of each of the five major sections of the course (that is, during the second class meetings of weeks 5, 8, 11 and 16 - see schedule of classes below). Writing these on a regular basis is intended to help you to do three things: a) to read, comprehend and analyse the texts that are set for the class more fully b) to begin to identify the connections (and contradictions) between different texts within and between different sections of the course c) to connect what you read to your own experience, and to your studies in other classes at AUK These four responses will form the largest single element of your grade for the course (40%): it is therefore worth writing them with as much care and thoughtfulness as you would give to an essay. Completed AQCIs will frequently form the basis for class discussion and debate. So what exactly is an “AQCI”....? AQCI stands for ARGUMENT, QUESTION, CONNECTIONS AND IMPLICATIONS. It is a structured response to one or more of the readings (other than the Ritzer textbook) set for the particular section of the course. Each AQCI should be structured so as to include the following 6 elements: 1. CENTRAL QUOTATION. Quote a sentence (or excerpts from linked sentences) from the text that you think is central to the author’s argument. Always fully cite the text and page from which you are quoting. 2. ARGUMENT. In a few (perhaps 3-4) sentences, state what you understand the author’s (or authors’) implicit or explicit argument to be in the text that you are referring to. You should state both what you think the author is arguing for, and, where appropriate, what s/he is arguing against. 3. QUESTION. Raise a question which you think is not fully or satisfactorily answered by the text. This should be a question of interpretation, rather than just one of fact. 4. EXPERIENTIAL CONNECTION. In a few sentences, say how the argument that you have mentioned is confirmed or contradicted by your own experience, by that of someone or some group else, or common sense. In your experience, is the author’s argument plausible or problematic, and why? 5. TEXTUAL CONNECTION. How does the argument of the text(s) you are referring to connect with, support, contradict or undermine the observation or argument of some other text which you have come across in this, or any other AUK course. If you can, present a quote from the other text (citing it properly) and explain how, in your opinion, the present text’s argument contradicts with, confirms, clarifies, elaborates or in some way interacts with the other text’s argument or point. This will become easier as the class progresses and we begin to identify the similarities - and contradictions of opinion - between the different theorists we read. However, you should not feel restricted to using other class texts for comparison - the “text” for connection might be something you read in the paper, a report you saw on television, an article you read for another class entirely... 6. IMPLICATIONS. In a few sentences, discuss what you think are the implications (znacheniia, posledstviia) of this argument (the one stated in #2 above) are for our understanding of some aspect of the social world. In what way does the argument shed light on things for us today, for the different ways we could order our own world, for resolving some of the pressing social issues facing Kyrgyzstan and the wider world? You may find it helpful (at least initially), to lay out your answer as six separate elements. When you feel more confident, you might want to try linking the six elements of the answer into a single, continuous response. So long as your AQCI is comprehensible, faults of English grammar and style will not be penalised in the assessment. It is much better that you attempt to express your ideas (even at the cost of linguistic inaccuracies) than that you produce a text which is grammatically sound but thoroughly unoriginal. Assessment and grading In summary, the different sections of the course are weighted like this: Attendance, class participation and timeliness of written work Mid-term exam Final exam 4 AQCIs 20 points 40 points 60 points 4 X 20 points 10 % 20 % 30 % 40 % Total possible 200 points 100 % Grades will be awarded on the following basis: 170 points and over 150-169 points 130-149 points 110-129 points under 110 points A B C D F Practicalities This is a 3-credit course, and the assumption is that students will be putting in 2-3 hours outside the classroom for every classroom hour. That means not just skimming through the text each week, but really reading through in detail, asking yourself it there are aspects you don’t understand, and checking out other books, or coming to see the instructor during office hours, to try to make clear those aspects which are proving more difficult. If you are experiencing difficulties with the course - with the workload, the readings, following the lectures etc. - please let me know! I am very happy to adapt the course to meet the needs of students who are taking it, but I do not read minds, so do come and talk to me. I am sensitive to the fact that many AUK students are juggling full-time study with employment outside the University and that this can be a difficult act to manage. However, I am also of the opinion that class time must take priority over any paid employment you may have, and that it is your responsibility to make sure that your employer is aware of your academic schedule. If, for any reason, you are unable to attend a particular class please contact me in advance- I am much more sympathetic about absences if I know about them in advance. Consistent absences without the support of a doctor’s note will not be tolerated and students missing too many classes will be dropped from the course. Occasionally, my CEP outreach obligations mean that I will not be present for a particular class. In such situations I will inform students in advance, and will endeavour wherever possible to schedule in a make-up class at the earliest opportunity. SCHEDULE OF CLASSES ______________________________________________________________________________________ ____ SECTION I: THE SOCIOLOGICAL IMAGINATION Week 1a Introductions Week 1b Critical reading and writing skills Topics for discussion: Reading critically and writing for comprehension; making theory your own; thinking and contextually. Reading: University of Victoria Counselling Services, ‘Reading to Comprehend and to Learn’ [WWW site]: http://www.coun.uvic.ca/learn/program/handouts/psqr5.html Daniel Chandler, 1995. ‘Writing Academic Essays’ [WWW site] http://www.aber.ac.uk/~ednwww/Undgrad/writess.html University of Chicago, ‘Conceiving, Composing and Critiquing a Paper’ Week 2 Thinking sociologically Topics for discussion: What is theory and why do we need it? Changing conceptions of sociology as a discipline; the problem of canons and those who get left out; “transitions” and why the classics might still be relevant; recurrent themes and debates. What is the relevance of a West European canon for Kyrgyzstan? What is its relevance personally? Reading: Zygmunt Bauman, ‘Sociology: What For?’ from Thinking Sociologically. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 1990: 1-19. Charles Lemert, ‘Social Theory: Its Uses and Pleasures’ from Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 1999: 1-20 Craig Calhoun, ‘Whose Classics? Which Readings? Interpretation and Cultural Difference in the Canonization of Sociological Theory’ from Stephen Turner, (ed.), Social Theory and Sociology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. 1996: 70-96 ______________________________________________________________________________________ ____SECTION II: PROGRESS AND ITS PROPHETS Optional: Week 3 Origins I. France: Enlightenment, Revolution and Reaction. Topics for discussion: Enlightenment roots; the double revolution and its impact in France; science, positivism and early sociology in France. How much are our ideas the products of our age? Can we ever really know how others felt and thought? Is society “progressing” or “regressing”? Reading: George Ritzer, ‘Intellectual forces and the rise of sociological theory’ from Sociological Theory: Fourth Edition New York: McGraw-Hill. 1996, p. 9-15 (as far as Durkheim), p. 16-17 (biography of Comte) Marie-Jean Condorcet, ‘Sketch of a Historic Tableau of the Progress of the Human Mind’ (1822) from Lester Crocker (ed.), The Age of Enlightenment: Selected Documents. London: Macmillan. 1969: 304-11 Auguste Comte, extracts from The Positive Philosophy (1840-42), in Henry Aiken, (ed.), The Age of Ideology. New York: New American Library. 1956: 124-137 Optional: Industrial and Krishan Kumar, ‘New Worlds’ from Prophecy and Progress: The Sociology of Post-Industrial Society. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1977: 13-44 Week 4 Origins II. Britain: Empiricism, Evolution and Reform Topics for discussion: Britain’s industrial revolution and its impact on social and political thought. Darwin, evolution and “social Darwinism”. The roots of individualism and empiricism. What is the relationship of the natural and social sciences? Are the latter just an extension of the former? Reading: New George Ritzer, ‘The Origins of British Sociology’ from Sociological Theory, 4th Edn. York: McGraw Hill, 1996: 31-37 Ernst Mayer, ‘Darwin’s Influence on Modern Thought’. Scientific American, Jul 2000: 67-71 MacMillan. Herbert Spencer, ‘Social Structure and Social Function’ (1897) from Lewis Coser and Bernard Rosenberg (eds.), Sociological Theory: A Book of Readings. New York: 1982: 466-471 Week 5 Origins III. Germany: Romanticism, Historicism, Dialectic Topics for discussion: The context of 19th Century German social thought; Kant, Hegel and the Young Hegelians. Romanticism and conceptions of historical change. Evolution, dialectic, revolution: how should we best account for historical change? Reading: Sociological George Ritzer, ‘The Development of German Sociology’ and ‘Karl Marx’ from Theory, 4th Edn. New York: McGraw Hill, 1996: 20-25 and 41-50 Optional: Political J.S. McClelland, ‘The Hegelian Context of Marxism’ from A History of Western Thought. London and New York: Routledge. 1996: 520-540 Eric Hobsbawm, ‘Science, Religion, Ideology’ from The Age of Capital, 1848-1875. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson. 1995 [1962]: 251-254; 258-271 Friday meeting of week 5: 1st AQCI due ______________________________________________________________________________________ ____ SECTION III: THE DARK FACE OF MODERNITY Week 6 Marx before Marxism: alienation in the modern world Topics for discussion: Marx’s biography, intellectual and social influences and context. Concept of alienation. Historical materialism. Alienation in the contemporary world. Can we regain our ‘speciesbeing’ in the modern world of work? Does technology render the world more or less alienated? (ed.), George Ritzer, ‘Human Potential’ and ‘Alienation’ from Sociological Theory, 4th Edn. York: McGraw Hill, 1996: 50-61 Karl Marx: ‘Preface to A Critique of Political Economy’ (1859), in David McLellan Karl Marx: Selected Writings. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 1977: 388-391 Karl Marx: ‘Preface’ and ‘Alienated Labour’ from The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844), in David McLellan (ed.), Karl Marx: Selected Writings. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1977: 76-87 Optional: Karl T. B. Bottomore and Maximilien Rubel, ‘Marx’s sociology and social philosophy’ from Marx: Selected Writings in Sociology and Social Philosophy. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1961:17-43 Reading: New Week 7 Durkheim on Anomie and Suicide Topics for discussion: Context of, and influences upon, Durkheim’s thought. Durkheim as sociologist: the forging of a discipline. Society sui generis. Are there such things as social facts? Anomie and suicide as social phenomena. Anomie vs. alienation. Mrs. Thatcher once said that ‘there is no such thing as society’. What do you think she meant by this? Do you agree with her view? Is the individual prior to society, or the other way round? Is society more than the sum of its parts? Reading: McGraw(as far as Social Theory: The George Ritzer, ‘Emile Durkheim’ from Sociological Theory, 4th Edn New York: Hill, 1996, p. 75-79; 82-83 (Durkheim’s biography), p. 84 (on anomie), p. 86-92 section on religion) Emile Durkheim: ‘Anomie and the modern division of labor’ (1902), ‘Sociology and Facts’ (1897) and ‘Suicide and Modernity’ (1897) in Charles Lemert (ed.), Social Multicultural and Classic Readings. Boulder, CO: Westview. 1999: 70-82 Optional: Raymond Aron, ‘Le Suicide’ in Main Currents in Sociological Thought II. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. 1970 :33-45 Week 8 Weber and the “iron cage” of modern life Topics for discussion: Weber: biography and its impact upon his social and political thought. Weber’s iron cage of bureaucracy: its origins, effects and contemporary forms; ‘McDonaldization’ as a contemporary manifestation? Is the modern world ‘an iron cage’ of bureaucracy? If so, how might we escape it? If not, where was Weber’s prediction wrong? Reading: George Ritzer, ‘Max Weber’ from Sociological Theory: 4th Edn. New York: McGrawHill, 1996, p. 109-122; 146-150 (on religion and the rise of capitalism) Max Weber, ‘Asceticism and the Spirit of Capitalism’ (1904-5) from The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge. 1992:155-183 Optional: Essays Max Weber, excerpts from ‘Bureaucracy’ in Gerth and Mills (eds.), From Max Weber: in Sociology. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1970 :196-209, 221-230, 240-244 Friday meeting of Week 8: 2nd AQCI due and in-class Mid-term exam ______________________________________________________________________________________ ____SECTION IV: ORDER, CONFLICT AND REVOLUTION Week 9 Marx on class conflict and revolution Topics for discussion: Marx’s historical materialism; ideas of class, conflict and revolution. Marx and subsequent Marxisms. Is class still a relevant concept? Is a truly proletarian revolution still possible? Does the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and Central Asia invalidate Marx’s theory? Charles Westview. George Ritzer, ‘Capital’ (to end of chapter) from Sociological Theory: 4th Edn. New McGraw-Hill, 1996, p. 64-74 Karl Marx and Frederick Engels extracts from ‘The Communist Manifesto’ (1848) in Lemert (ed.), Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings. Boulder, CO: 1999: 37-41 Optional: Karl Karl Marx, ‘Inaugural Address to the First International’, (1864) in McLellan, (ed.), Marx: Selected Writings . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1977: 531-537 Reading: York: Week 10 Weber: Power, authority, responsibility Topics for discussion: Weber’s dialogue with Marx; class and status; types of authority. The responsibilities of the politician and scientist. Who really holds power in our world today? Politicians? Businessmen? The media? What kind of authority, if any, do they have? Press. George Ritzer, ‘Class, Status and Party’ (as far as section on rationalization) from Sociological Theory, 4th Edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996, p. 126-135 Max Weber, selections from ‘Socialism’ (1918) in Lassman and Speirs, (eds.), Weber: Political Writings, ed. Lassman and Speirs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University 1996: 287-303 Optional: Max Max Weber, selections from ‘Politics as a Vocation’ in Gerth and Mills, (eds.), From Weber: Essays in Sociology. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1970: 77-128 Reading: Week 11 Durkheim: Searching for Order Topics for discussion: Functions and orders in Durkheim’s work; the rationality of the ‘irrational’. Durkheim on religion and primitive classification. Do social structures determine social functions or the other way round? What makes some kinds of society more stable than others? Reading: Theory: George Ritzer, ‘The Division of Labor in Society’ and ‘Religion’ from Sociological 4th Edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996: 79-86, 92-95 Emile Durkheim, selections from ‘The Method of Determining this function’ from The Division of Labor in Society (1893) New York: The Free Press. 1999: 16-29 Optional: Cultural Emile Durkheim, ‘Primitive Classifications and Social Knowledge’(1903) and ‘The Logic of Collective Representations’ (1912) from Lemert (ed.), Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings. Boulder, Westview. 1999: 82-98 2nd Meeting of Week 11: 3rd AQCI due ______________________________________________________________________________________ ____ SECTION V: SELVES AND OTHERS Week 12 Simmel: Strangers, others and selves Topics for discussion: Influences upon Simmel’s thought; the importance of the “micro”-world; levels of social reality, the impact of numbers upon types of interaction. To understand the social world, should we start from micro-structures of small-scale interaction and build upwards, or should we look at the macro-level and examine how it impacts upon the micro-forms? How might Marx and Simmel have addressed this question? Reading: McGrawMulticultural Optional: (eds.), York: George Ritzer, ‘Georg Simmel’ from Sociological Theory, 4th Edn. New York: Hill, 1996, p. 155-168 (as far as section on social structures) Georg Simmel, ‘The Stranger’ (1908) from Lemert (ed.), Social Theory: The and Classic Readings. Boulder, Westview. 1999.184-188 Georg Simmel, ‘The Dyad and The Triad’ from Lewis Coser and Bernard Rosenberg Sociological Theory: A Book of Readings. New York: MacMillan. 1982: 45-53 Louis Coser, ‘Georg Simmel: The Work’ from Masters of Sociological Thought. New Harcourt Brace Janovich, 1977: 177-194 Week 13 Cooley and Mead: “Looking-glass selves” Topics for discussion: Cooley, Mead and the origins of symbolic interactionism. Behaviourism, and the importance of observable behaviours. Symbols, interpretation and the importance of language. What gives ‘me’ my identity? My genes? My parents? My surroundings? How should we balance “nature” and “nurture” in accounting for individual personality and behaviour? George Ritzer, ‘The Ideas of George Herbert Mead’ from Sociological Theory, 4th Edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996, p. 332-351 (up to section on Erving Goffman) Cooley, ‘The Looking-Glass Self’ from Lemert (ed.), Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings. Boulder, Westview. 1999: 188-189 Mead, ‘The Self, the I, and the Me’ from Lemert (ed.), Social Theory: The Multicultural and Classic Readings. Boulder, Westview. 1999: 224-229 Reading: ______________________________________________________________________________________ ____ SECTION VI: EMBRACING UNREASON Week 14 Nietzsche: Morality as the “danger of dangers” Topics for discussion: Nietzsche’s challenge to 19th Century assumptions, and his significance for the development of 20th Century social and political thought. The embracing of unreason and the challenging of morality. The (mis)-appropriation of Nietzsche. The challenges and insights of his work. Is there any “absolute” conception of morality, or are all conceptions of the “good”, and of right and wrong socially conditioned and socially determined? How might conflicting moral codes be reconciled? Reading: J.P. Stern, ‘Nietzsche in company’ from Nietzsche (Fontana Modern Masters Series). London: Fontana. 1978: 13-26 Optional: (1887) Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘Preface’ and ‘First Essay’ from On the Genealogy of Morality ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994: 3-37 Week 15 Le Bon: Crowds and Collective Psychology Topics for discussion: Dilemmas of democracy and fear of the “mob”. Modernity as the era of crowds. Gustave Le Bon’s background, influences and theory of the “mind of the crowd”. Reasons for the changing fate of Le Bon’s text. Do you/we act differently in crowds than we do as individuals? If so, why? Should we think of crowds having “a mind of their own?” How and by whom are they driven? Reading: Gustave Le Bon, extracts from ‘The Mind of Crowds’ from The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895). Harmondsworth, Penguin. 1960: 36-59 Optional: Study of Robert K. Merton, ‘The Ambivalences of Le Bon’s The Crowd’ from The Crowd: A the Popular Mind (1895). Harmondsworth, Penguin. 1960:v-xxxix Week 16 Freud: Civilization and its discontents Topics for discussion: Freud’s theory of the unconscious and its impact upon subsequent social and psychological thought. The relevance of Freud’s theories to the social world. Freud’s account of “civilization and its discontents”. The conflict between the demands of instinct and those of civilization. Is our behaviour in small (or large) part determined by unconscious drives and desires? How do we account for the rational and irrational aspects of personal and societal behaviour? Are the demands of instinct really in opposition to the demands of civilization? What did Freud think about the future of Western civilization? Do you agree with his assessment? Short James Strachey, ‘Sigmund Freud: A Sketch of His Life and Works’ from Sigmund Short Accounts of Psycho-Analysis. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963, p. 11-24 Sigmund Freud, ‘Lecture number 3 on Psycho-analysis’ from Sigmund Freud, Two Accounts of Psycho-Analysis. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963, p. 55-69 Optional: Civilization, Penguin. Sigmund Freud, extracts from ‘Civilization and its Discontents’ (1929) from Society and Religion. Volume 12 of the Penguin Freud Library. London: 1991: 251-340 Reading: Freud, Two Meeting 2 week 16: 4th AQCI due Week 17 Reading and exam week Meeting 2 week 17: In-class final exam