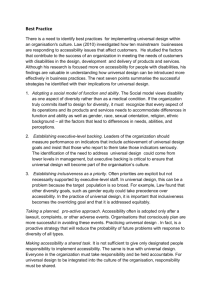

draft brief of the accessibility for ontarians with disabilities act

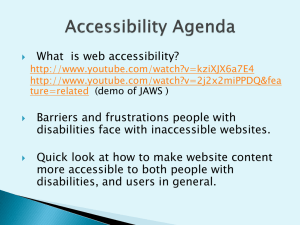

advertisement