the economy at full employment: the classical model 1 Ch24 The

advertisement

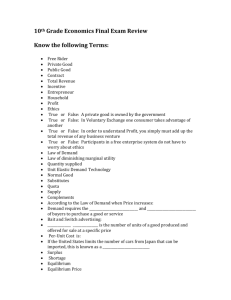

Ch24 The economy at full employment: The Classical Model I. The Classical Model: A Preview The Classical Model is introduced. 1. There are two distinct categories of variables that describe macroeconomic performance: a) Real variables: real GDP, employment and unemployment, the real wage rate, consumption, saving, investment, and the real interest rate. b) Nominal variables: the price level (CPI or GDP deflator), the inflation rate, nominal GDP, the nominal wage rate, and the nominal interest rate. 2. The separation of macroeconomic performance into a real part and a nominal part is the basis of the classical dichotomy. 3. The classical dichotomy states: “At full employment, the forces that determine real variables are independent of those that determine nominal variables.” 4. The classical model is a model of an economy that determines the real variables at full employment. 5. Most economists believe that the economy fluctuates around full employment, but that the classical model provides powerful insights into the level of full employment and potential GDP around which the economy fluctuates. II. Real GDP and Employment A. Production Possibilities 1. The production possibilities frontier (PPF) is the boundary between those combinations of goods and services that can be produced and those that cannot. 2. Figure 8.1(a) illustrates a production possibilities frontier between leisure time and real GDP. 3. The more leisure time forgone, the greater is the quantity of labor employed and the greater is the real GDP. 4. The PPF showing the relationship between leisure time and real GDP is bowed-out, which indicates an increasing opportunity cost: As real GDP increases, each additional unit of real GDP costs 168 CHAPTER 8 an increasing amount of forgone leisure. 5. Opportunity cost is increasing because the most productive labor is used first and as more labor is used, the labor used becomes increasingly less productive. B. The Production Function 1. The production function is the relationship between real GDP and the quantity of labor employed when all other influences on production remain the same. 2. One more hour of labor employed means one less hour of leisure, therefore the production function is the mirror image of the leisure time-real GDP PPF. 3. Figure 8.1(b) illustrates the production function that corresponds to the PPF shown in Figure 8.1(a). III. The Labor Market and Potential GDP A. The Demand for Labor 1. The quantity of labor demanded is the labor hours hired by all the firms in the economy. THE ECONOMY AT FULL EMPLOYMENT: THE CLASSICAL MODEL 2. The demand for labor, Figure 8.2, is the relationship between the quantity of labor demanded and the real wage rate when all other influences on firms’ hiring plans remain the same. 3. The real wage rate is the quantity of good and services that an hour of labor earns. a) 169 The money wage rate is the number of dollars an hour of labor earns. b) The average real wage rate is the average money wage rate divided by the price level multiplied by 100. c) 4. It is the real wage rate, not the money wage rate, that determines the quantity of labor demanded. The demand for labor depends on the marginal product of labor, which is the additional real GDP produced by an additional hour of labor when all other influences on production remain the same. a) The marginal product of labor is calculated as the change in real GDP divided by the change in the quantity of labor employed. b) The marginal product of labor diminishes as the quantity of labor employed increases, other things remaining the same. Diminishing marginal product occurs because all the labor employed works with the same fixed capital and technology, and is an example of the law of diminishing returns. c) The diminishing marginal product of labor limits the demand for labor. 170 CHAPTER 8 5. The demand for labor is the marginal product of labor. Figure 8.3 shows the production function, PF, in part (a). The production function determines the marginal product of labor. And the marginal product of labor curve is the demand for labor curve in part (b). a) Firms hire more labor as long as the marginal product of labor exceeds the real wage rate. b) Eventually, with the diminishing marginal product of labor, the extra output from an extra hour of labor is exactly what the extra hour of labor costs, which is the real wage rate. At this point, the profit-maximizing firm hires no more labor. c) When the marginal product of labor changes, the demand for labor changes. If the marginal product of labor increases, the demand for labor shifts rightward. B. The Supply of Labor 1. The quantity of labor supplied is the number of labor hours that all the households in the economy plan to work at a given real wage rate. 2. The supply of labor is the relationship between the quantity of labor supplied and the real wage rate when all other influences on work plans remain the same. 3. The quantity of labor supplied increases as the real wage rate increases for two reasons: a) Hours per person increase because the higher the real wage rate, the higher the opportunity cost of not working. There is an opposing income effect. The higher real wage rates increase household income, which increases the demand for leisure. An increase in the demand for leisure is the same thing as a decrease in the quantity of labor supplied. The opportunity cost effect is usually greater than the income effect over the relevant range for most U.S. workers, so a rise in the real wage rate brings an increase in the quantity of labor supplied. b) Labor force participation increases because higher real wage rates induce some people who choose not to work at lower real wage rates to enter the labor force. THE ECONOMY AT FULL EMPLOYMENT: THE CLASSICAL MODEL 4. The labor supply response to an increase in the real wage rate is positive but small. A large percentage increase in the real wage rate brings a small percentage increase in the quantity of labor supplied. Figure 8.4 illustrates a labor supply curve. 171 172 CHAPTER 8 C. Labor Market Equilibrium and Potential GDP 1. Labor market equilibrium occurs when the real wage rate is such that the quantity of labor demanded is equal to the quantity of labor supplied. Figure 8.5(a) illustrates labor market equilibrium. 2. Labor market equilibrium is fullemployment equilibrium. 3. The level of real GDP at full employment is potential GDP. Note that in Figure 8.5(a), labor market equilibrium occurs at 200 billion labor hours. Referring back to the production function in Figure 8.1, repeated as Figure 8.5(b), 200 billion labor hours means that potential GDP is $10 trillion. IV. Unemployment at Full Employment A. Unemployment always is present. 1. The unemployment rate at full employment is called the natural rate of unemployment. 2. The natural unemployment rate is always positive; that is, there is always some unemployment because of job search and job rationing. B. Job Search 1. Job search is the activity of workers looking for an acceptable vacant job. 2. All unemployed workers—frictionally, structurally, and cyclically unemployed — search for new jobs, and while they search many are unemployed. Job search unemployment, and how it relates to THE ECONOMY AT FULL EMPLOYMENT: THE CLASSICAL MODEL 173 the natural unemployment rate, is illustrated in Figure 8.6. 3. Job search can be affected by: a) Demographic change. As more young workers entered the labor force in the 1970s, the amount of frictional unemployment increased as they searched for jobs. Frictional unemployment might have fallen in the 1980s as those workers aged. Twoearner households might increase search, because one member can afford to search longer if the other still has income. b) Unemployment compensation. The more generous unemployment compensation payments become, the lower the opportunity cost of unemployment, so the longer workers search for better employment rather than any job. More workers are covered now by unemployment insurance than before, and the payments are relatively more generous. c) Structural change. An increase in the pace of technological change that reallocates jobs between industries or regions increases the amount of search. C. Job Rationing 1. Job rationing is the practice of paying a real wage rate above the equilibrium level and then rationing jobs by some method. 2. Job rationing can occur for two reasons: a) A firm pays an efficiency wage, which is a real wage rate set above the fullemployment equilibrium wage rate that balances the costs of benefits of this higher wage rate to maximize the firm’s profit. The higher wage rate attracts the most productive workers and then gives them the incentive to be productive so they do not lose their high-paying jobs. b) A minimum wage is the lowest wage rate at which a firm may legally hire labor. If the minimum wage is set above the equilibrium wage rate, job rationing occurs D. Job Rationing and Unemployment 1. If the real wage rate is above the equilibrium wage, regardless of the reason, there is a surplus of labor that adds to unemployment and increases the natural unemployment rate. 2. Most economists agree that efficiency wages and minimum wages increase the natural unemployment rate. a) Card and Krueger have challenged this view and argue that an increase in the minimum wage works like an efficiency wage, making workers more productive and less likely to quit. b) Hamermesh argues that firms anticipate increases in the minimum wage and cut employment before they occur. Therefore, looking at the effects of minimum wage changes after the change occurs misses the effects. 174 CHAPTER 8 c) Welch and Murphy say regional differences in economic growth, not changes in the minimum wage, explain the Card and Krueger theory. V. Investment, Saving, and the Interest Rate A. Potential GDP depends on the quantity of productive resources, including capital. 1. 2. 3. The capital stock is the total amount of plant, equipment, buildings, and inventories, physical capital. Gross investment is the purchase of new capital. Depreciation is the wearing out and scrapping of the capital stock. Net investment equals gross investment minus depreciation; net investment is the addition to the capital stock. Investment is financed by saving, which equals income minus consumption. The return on capital is the real interest rate , which is equal to the nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation. The real interest rate is approximately equal to the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. B. Investment Decisions Business investment decisions are influenced by: 1. The expected profit rate. The expected profit rate is relatively high during expansions and relatively low during recessions. Increases in technology can increase the expected profit rate. Taxes affect the expected profit rate because firms are concerned about the after-tax profit rate. 2. The real interest rate. The real interest rate is the opportunity cost of investment. An increase in the real interest rate decreases the number of investment projects that are profitable. C. Investment Demand 1. Investment demand is the relationship between investment and the real interest rate, other things remaining the same. 2. The investment demand curve, illustrated in Figure 8.7, plots the relationship between investment demand and the real interest rate. a) The investment demand curve slopes downward. A rise in the real interest rate (say from 4 percent to 6 percent) decreases the quantity of planned investment demanded (from $1.2 trillion at A to $1.0 trillion at B) along investment demand curve ID in Figure 8.7. b) If the expected profit rate increases, the investment demand curve shifts rightward. THE ECONOMY AT FULL EMPLOYMENT: THE CLASSICAL MODEL 175 D. Saving Decisions 1. Households divide their disposable income between consumption expenditure and saving. 2. Saving is affected by the real interest rate, disposable income, wealth, and expected future income. 3. The higher the real interest rate, the greater is a household’s opportunity cost of consumption and so the larger is the amount of saving. 4. The larger disposable income, the greater is a household’s saving. 5. The greater is a household’s wealth, the greater is its consumption and the less is its saving. 6. The higher a household’s expected future income, the greater is its current consumption and the lower is its current saving. E. Saving Supply 1. Saving supply is the relationship between saving and the real interest rate, other things remaining the same. 2. Figure 8.8 shows a saving supply curve, which slopes upward because a rise in the real interest rate increases saving. F. Equilibrium in the Capital Market 1. In the U.S. economy, there are many interrelated capital markets. Because funds can flow from one market to another, we can think about the capital market as a whole. 2. The real interest rate is determined by investment demand and saving supply. 176 CHAPTER 8 3. In Figure 8.9, ID is the investment demand curve, SS is the supply of saving curve, and the equilibrium real interest rate is 6 percent. At the equilibrium real interest rate, there is neither a shortage nor surplus of saving. VI. The Dynamic Classical Model A. The Classical Model also has implications for how the economy changes over time. B. Changes in Productivity 1. Labor productivity is real GDP per hour of labor. 2. Three factors influence labor productivity. a) Physical capital: An increase in capital increases labor productivity. b) Human capital: Human capital is the knowledge and skill that people have obtained from education and on-the-job-training. An increase in human capital increases labor productivity. c) 3. Technology: An increase in technology increases labor productivity. When labor productivity increases, the production function shifts upward and potential GDP increases. THE ECONOMY AT FULL EMPLOYMENT: THE CLASSICAL MODEL C. An Increase in Population 1. Figure 8.11 (mislabeled as Figure 8.12) illustrates the effects from an increase in population. 2. An increase in population increases the supply of labor and the supply of labor curve shifts rightward. The equilibrium real wage rate falls and the equilibrium quantity of employment increases. 3. The increase in employment leads to a movement up along the production function so that potential GDP increases. However, diminishing returns means that potential GDP per hour of work decreases. 177 178 CHAPTER 8 D. An Increase in Labor Productivity 1. Figure 8.12 (mislabeled as Figure 8.11) illustrates the effects from an increase in labor productivity. 2. An increase in labor productivity can be the result of an increase in physical capital, an increase in human capital, or an advance in technology. In all cases, the production function shifts upward and the demand for labor increases so that the demand for labor curve shifts rightward. The increase in the demand for labor raises the equilibrium real wage rate and increases the equilibrium quantity of employment. 3. The increase in employment leads to a movement up along the production function. In addition, the increase in labor productivity shifted the production function upward. Both effects increase potential GDP. The upward shift of the production function means that potential GDP per hour of work increases. THE ECONOMY AT FULL EMPLOYMENT: THE CLASSICAL MODEL E. Population and Productivity in the United States 1. In the United States, over the past two decades, both the population and labor productivity have increased. 2. Figure 8.13 illustrates these effects. 3. The increase in the demand for labor exceeded the increase in the supply of labor so that the real wage rate rose. Employment increased as a result of both the increase in the demand for labor and the increase in the supply of labor. 4. The increase in productivity shifted the production function upward. That, combined with the increase in employment, increased potential GDP. 179