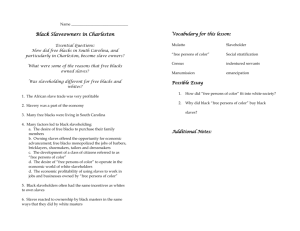

black and white

advertisement