Link to Draft

advertisement

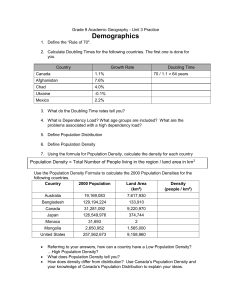

João Pedro Volz The Population Bomb By: Paul R. Ehrlich Debating Overpopulation I. Overview Few would argue that there has been a more influential book in the subject of human overpopulation as the population bomb. Paul Ehrlich’s work was not the first work on the subject and concerns about a rapidly growing human population were noted in the 1950’s and 60’s. Ehrlich’s charisma was influential though in making the subject so widely known that it more or less ended the popular debate for decades after its publication. In his book, Ehrlich poses scenarios to illustrate the hopeless situation the modern world found itself in when a geometrically expanding population vies for limited resources. Today, thanks in good part to this work the average person holds fast a belief in human overpopulation. Though a best seller at its time, the book is no longer widely read as the primary source for the subject, it has though influenced every level of the population from world leaders to cartoonists. What makes this relevant to the purposes of this course is the question of whether these beliefs founded in truth, or has our generation taken many of the claims put forth by Ehrlich and other Malthusians for granted? The truth is likely somewhere in between. II. Body of the Review Ehrlich organized the Population Bomb into Several sections meant to outline the problem, what is currently done to solve the problem, and what needs to be done to suspend the catastrophic conclusions he predicted. Intermitted between these are some doomsday scenarios he has predicted which largely did not come to pass, and which he said were not the factual focus of his work. a. Content The problem, as he states, is threefold: too many people, too little food, and a dying planet. Too many people, he explains, is the result of high birth rates, versus death rates, and that the doubling rate for populations had been decreasing dramatically in the 20th century. Doubling rate is the amount of time it takes for the population of a specific geo-political area to double. In 1968, the doubling time for the world was around 35 years. He illustrates the problem of this low doubling time by explain that the doubling time was about 1000 years from 8000 B.C. to 1650 A.D.. The next doubling took about 200 years. In 1850, the next doubling took about 80 years, and in 1930, the population reached about 2 billion. By showing, the wide range of geographic time that it took to double populations he then continues using the 35-year doubling rate to show how in 900 years the world would have sixty million, billion people. These double rates are not consistent throughout the world population. Under developed countries tend to have higher doubling rates then what he calls over-developed countries. The problem is also one of distribution, a most of the world’s over-developed countries consume more than their fair share of the world’s resources while under-developed countries see the affluence of the over-developed countries as something to strive for. Even within countries, the population problem is exacerbated by the fact that large numbers of people constantly migrate and reside in major urban centers. The population increase will continue so long as birth rates, measured by births per thousand per year, are greater than death rates, measured by deaths per thousand per year. He uses that calculation to show how the doubling times will continue to decrease in the years to come. Ehrlich uses the end of the chapter to go through what in his views are the evolutionary reasons behind the high reproductive rates and the human drive to continue reproducing. Overpopulation itself would not be a catastrophic problem if was not for a limited food resource. Ehrlich illustrates this fact by showing statistics of malnutrition around the world, which were likely understated by various factors. Malnutrition isn’t something that people easily die from instantly, and people generally don’t directly die of malnutrition but have malnutrition as one of the primary reasons why they suffered from what they died from. He adds that underreporting of malnutrition is also because it is not a flashy death but rather a slow and painful one deemed uninteresting to the media. Ehrlich brings up statistics on how the worlds food production has halted and in some years decreased in the 20th century, and how all but 10 countries produced more food then they consumed, the United States being one of the only truly populous nations to do so. A good amount of the food production in the world is also problematically turned to feed. Ehrlich describes how the higher up the food chain we find our food the less efficient the transfer of energy will be. This is the primary reason why species are less populous the higher they are in the food chain. The problem isn’t as simple as food production, but also the diversity of food production. In order for humans avoid malnutrition, they must consume a balanced diet. He states that poor people around the world subsist mainly on an undiversified amount of plant foods. Proteins food sources cost a lot of plant food to maintain but provide us with a valuable source of amino acids and other nutrients necessary for human growth and development. He ends his section on the problems of food production with the fact that even if there was enough and sufficiently diverse food, the problem of distribution would still be a factor. Over-developed countries consume more than the lion’s share of the world’s food resource leaving the under-developed countries with severe problems. Ehrlich makes the statement that the planet is dyeing due to human overpopulation. He brings up several statistics concerning pollution and environmental decay and then explains that the problem is the human beings destroy complex ecosystems and create simple ones. To illustrate this fact he brings up the growing concerns about pesticides, namely DDT, and their effect on the environment. In a complex ecosystem, such as a rainforest, extinction of one single species would not be a tremendous problem. For example if a species of fox which is the main predator of rodents in the rain forest were to disappear, it would not lead to overpopulation of the rodent community, since the ecosystem is diverse enough where another predator would take the place of the now extinct animal. In simple ecosystems, this would be more problematic. Take for example the elimination of a species of pests, which live off our agricultural products by use of pesticides. The populations of other species consumed by the very pest we eliminated would skyrocket because farmlands are simple undiversified ecosystems. This would lead to the growth of a new pest. Modern human cities also create unbalanced simple ecosystems. If we look at a major metropolitan area, we generally find an abundance of rodents and a lack of their natural predators. This is far from the only effect humans have on the environment. Wars have reached level where we have the potential of creating irreparable damage to the planet. Ehrlich believes even a smaller population would damage the environment and decay our natural resources, but through advances in technology and a population limited to about 500 million humans, there is a chance we could create a sustainable environment. In chapter 3, Ehrlich conducts and analysis of what is currently done to curtail the problems above, and why those efforts are grossly ineffective. He begins the chapter with the false idea that the Catholic Church only allows the seemingly ineffective use of the rhythm method as birth control. He then goes on to state that all forms of family planning suffer the same problem of being voluntary. He believes that birth control will not be a solution so long as people are allowed to decide how many kids they want. Aside from this problem, he presents the problem of a government that is all too content to deliberate about the problem without taking effective action. He brings several examples of action taken in India, and how the lack of education and politicization of concerns with birth control the programs were largely unsuccessful. One example is the government sponsored supplying of IUDs vasectomies, and condoms, which failed due to public disinterest and false rumors of the dangers of IUD’s. The United States he states has also been slow to action and only recently (for 1968) began using public money to research and provide contraceptives. He also praises the liberalization of abortion laws that occurred in this time in the USA, but felt that the UN’s opposition to supporting liberalized abortion programs was a problem. He praises Japan’s increased access and allowance of abortions. Ehrlich also discusses how controlling the death rate with improved science and medicine is problematic in the face of an uncontrolled birth rate. He believes that science’s focus in extending our lives will only doom humanity in the end. Ehrlich continues in the chapter describing how efforts to increase farmable land are essentially fruitless. Much of the unfarmed land left in the world is not ideal for farming. He cites efforts by the Soviet government to force expansion of farmland and its failures, and goes on to explain how farming the rain forests will destabilize the soil creating hard rock and lead to similar failure. Environmentalist movements, he feels are also inadequate and despite being a move in the right direction, it is a moving done too little too late to avoid what will happen. He begins the chapter on “what needs to be done” with the suggestion that there should be an increase in contraception and education focused on making sexual activity outside of marriage acceptable. He believes marriage should be viewed as only for people who would be adequate parents and would provide for a positive environment for child rearing, instead of serving as a default option. He then goes on to Criticize Pope Paul VI for the encyclical Humane Vite which, which entrenched the Church’s position against contraception, claiming that the pope was not dedicated to life or social justice but rather to increasing the world’s death rate. He goes on to explain how the decision was met with huge opposition by members of the church and people outside the church alike and that petitions were written to convince the Pope to change the Church’s position. He also criticizes economists for viewing humans as nothing more than potential consumers and faults them for creating a system, which is dependent on constant human expansion. b. Criticisms The main body of criticism I have against his work is that his dystopic prediction have failed to come true. The modern world finds itself facing potentially the opposite problem. Despite what he believed, birth control and family planning initiatives have been quite successful at curtailing the growth rate of the world population. The world population is still technically increasing to this day, but it isn’t because of increased birth rates, but rather due to a rapidly decreasing death rate. This goes for over and under developed countries. The most accurate way to determine increases in population is by measuring the children had by the average woman. If every woman were to have 2.1 children, the world population would stabilize and even slowly begin to decrease. This is something he mentioned in his book. Well a modern view of the world today will show that most over-developed countries have a rate of less than 2.1 children per woman, and most under developed countries have the rates of children per women decreasing steadily every year. This is in large part due to increased support for population control programs around the world, and populations that are either voluntarily or forcibly having fewer children. Overall this highly problematic to under-developed countries where governments have not produced safety nets to care for the elderly. For example, the rural poor of Nigeria had a relatively large birth rate of six children per woman. This is something that Ehrlich would view as appalling, but when half of the children did not reach reproductive age, the statistic became inflated. Furthermore, if we were to observe that extended family units in these population depended on their children and grandchildren to provide for them in old age, the burden on each individual child would become increasingly unbearable. Food resources have also begun to dramatically increase with the advent of genetic engineering and new agrarian technologies. Scientists can now create crops resistant to harsh environments or pests, a fact that is eliminating the need for pesticides. The genetic engineering phenomenon is also present in protein rich foods, which are now developed to provide more food while consuming less. This isn’t to say that genetic engineering is without its faults or dangers. Interest worldwide for renewable sources of energy and development of cleaner fuels are also under works. Development in these areas couples with the discovery of new resources each year is leading to a world where scarcity is not the cause of human suffering. Instead, we should look at wars and the misdistribution of resources as the causes of scarcity problems. This is leading to an increasingly aging population and longer spans between generations, as people are having fewer kids later in life. This could prove problematic for the world economy. The last big generation was the baby-boomers, who when this book was written, might have lead Ehrlich to believe in a lot of what he states above, but we are sure to see severe economic problems now that the baby boomers are entering retirement and leaving the workforce, and a potential static drop in the world population when they die. This has begun to concern many countries around the world, several of which have instituted programs of subsidizing births with monthly stipends. I think though, that the most fundamental error made by Ehrlich is his devaluing of the human person. His work shows a clear belief that people are burdens on society, the economy, and the world, when in fact human beings are innovators and problem solvers. Increases in population since this book’s publication have been equally met with increases in the number and quality of education, development of new technologies, decrease in the worldwide rates of malnutrition, and a general increase in human empathy and awareness towards global problems. It is no surprise that the rapid increase in scientific development is associated with large increases in population. His conclusions were logically drawn, and the work will go down as one of the most popular restatements of Malthusian thought in recent history. Despite his logically based hypothesis, world-renowned economists, demographers, and anthropologists have done much to discredit many of his basic assumptions. c. The Galileo Dilemma I see one of two potential Galileo dilemmas present in this book. The first is the potential that his theory is wrong, and that the opposite is true (the rapid decrease in human population) ends up ignored because of the politicized hype produced by this book and others, which followed a similar line. The second potential Dilemma is that his conclusions are still mostly true, and whole segments of the population, mostly religious people, refuse to believe it leading to the dystopia he predicted. The power in this scenario is the widespread belief of the people and actions of the world governments, and NGO’s, and weather people will separate themselves from the politicization of the issue and open-mindedly seek the truth of the matter.