tax update

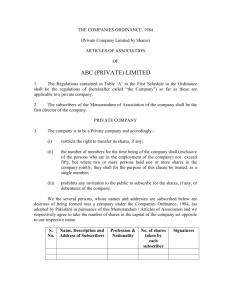

advertisement