(projdoc).

Osmond Mugweni

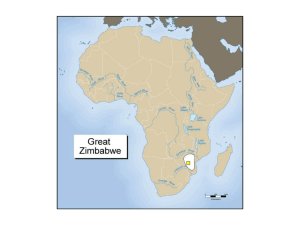

Country: Zimbabwe

Field(s) of Work: Environment, Environment

Land Management, Agriculture, Bio-diversity Protection, Cooperatives

Organization: The Njeremoto Enterprises

Location: Masvingo

Note: This profile was prepared when Osmond Mugweni was elected to the Ashoka

Fellowship in 2003.

Working in arid and semiarid regions of Zimbabwe, Osmond Mugweni encourages small and large-scale livestock farmers to adopt a collective land management system to improve productivity and halt desertification.

The New Idea

Imported during the colonial era, the livestock practices used for decades in Zimbabwe have destroyed land, decreased productivity of livestock farmers, and accelerated desertification, which threatens not only Zimbabwe but many parts of the African continent. To steer livestock farmers toward a solution from which they can see immediate and long-term benefits, Osmond has developed a land management system that melds components of traditional knowledge and farming practices with modern agricultural techniques. He trains farmers to herd collectively, allowing them to maximize their holdings and partition large tracts of land. His approach prevents overgrazing–and the irreversible soil erosion it precipitates–by carefully regulating grazing to allow each portioned area to fully recover between grazing cycles. Osmond has shown that this approach yields useful environmental, economic, and social benefits: it ensures long-term sustainability of arid and semiarid regions; it brings together farmers in a collective endeavor from which they earn more money; and it restores the farmers' connection to each other and to the land. Osmond is working through universities in the

U.K. and elsewhere to share his methodology more broadly with academics and development workers.

The Problem

The current management practices of land set aside for cattle ranching in Zimbabwe have disrupted the ecological stability of the grazed areas. The conventional ranching method is simply to release a certain number of cattle into a given holding and allow them to graze at will. Within this system, it is believed that the key to maintaining healthy pastures is controlling animal numbers in a way that ensures proportionate allocation of grazing areas to herd size. In arid or semiarid areas in Zimbabwe, this method does not

allow time for grasslands to fully recover between grazing periods. The result, over time, is scarcity of food for the cattle and soil erosion, which leads to desertification.Today's technologies replaced the prevailing traditional systems instead of upgrading them or tailoring them to the local environment. This rejection of traditional knowledge systems was understandable during the colonial era when conversion to contemporary methods was coercive, but in periods afterwards, it was particularly baffling as many of these methods did not work in Zimbabwe. The success of the conventional system of livestock farming is also based on the belief that all land in the world exhibits biological decay due to the abundance of moisture distribution throughout the year. The process enables rested pasture to rejuvenate quickly in two ways: rapid decomposition of dead matter that recycles essential nutrients back into the soil and rainfall that carries nourishing minerals.

Osmond has observed that this is true of Western European grasslands and the equatorial zones of Africa but not in semi arid rangelands such as those in Zimbabwe, where due to the low and uneven distribution of annual rainfall, nutrient recycling is prolonged. Decay starts as an oxidation process and only becomes biological when the plants have fallen to the ground. According to Osmond, another assumption of this system–that regulating animal numbers will prevent overgrazing–is responsible for land degradation. Osmond's pilot research suggests that if the recovery periods are not regulated, even one animal can cause overgrazing. That is, if animals graze continuously on a given plot of land or return to graze before the plants have fully recovered, degradation is certain to occur. It is no wonder, then, that the conventional ranching system and other unsustainable agricultural practices threaten Zimbabwe's ecological stability. It is estimated that as a by-product of soil erosion, the country is losing Z$240 million (approximately US$4.5 million) of nitrogen and phosphorus each year from the arable lands and 2.5 million tons of organic matter essential to soil stability and fertility. The soil on most agricultural land has been depleted to its minimum productivity potential, thus seriously limiting yields and substantially increasing environmentally destructive inputs. In short, Zimbabwe is increasingly facing desertification and economic collapse, as farmers are unable to find grasslands for their cattle.

The Strategy

Because Osmond's approach, which is based on his own path breaking research in

Zimbabwe, runs counter to conventional farming practices, he recognizes that a successful pilot is central to introducing his work more broadly. Therefore, he has obtained a 223.4-hectare research farm that he uses as a research and training center. At the farm, Osmond trains livestock farmers in land management techniques that he has pioneered and refined over sixteen years. He teaches them to divide their collective lands into units to monitor grazing, allowing pasturelands time to fully recover before the next grazing cycle. Osmond's extensive research has revealed that each land unit in semi-arid or arid rangelands should be grazed for short but intense grazing periods, followed by long recovery periods of about 90 days during fast growth conditions (wet season) and

120 days during slow growth conditions (dry season). This system adjusts for land-sizes– for small farms, Osmond teaches communal herding, encouraging farmers to tear down their fences, subdivide their land, and collectively allocate grazing areas according to a

grid. One area is left arable for growing crops, another is grazed in early summer, the third is grazed only in late summer and the fourth is left to recover.Using his research farm as the center of his work, Osmond is reaching out to farmers by radio and newsletters. He trains both small-scale and commercial farmers at the center and encourages farmer-to-farmer exchange visits in satellite communities. The work will strengthen farmer-to-farmer learning and will transform the conventional top-down transfer of knowledge to a participatory process. Osmond aims to develop a program that links farmers, researchers, and agricultural agents to refine the techniques he has developed and to introduce them broadly. Osmond believes that this system is more sustainable than the current one because the farmer is actively engaged in tracking his results and improving the techniques for others to use. Osmond sees that sharing his work and methodology with the international scientific community will enable him to quickly reach areas similar to Zimbabwe in climate and culture. He is working with a university in the U.K. to publish the results of his work. Using his research farm as a hub, he plans to host internships and internships seminars and conferences at his farm. Through these means, he intends to introduce his rangeland management practices in arid and semiarid regions around the world.

The Person

Osmond Mugweni's early childhood was spent with his grandfather, who related stories of the beauty of the land, the rich biodiversity and the abundant wildlife. As a youngster, from 1956 to the late 1960s, he used to herd cattle and enjoy swimming and fishing in local rivers and streams. His particular delight was spending time with his friends, catching fish that were swimming up stream. Since then the beautiful environment that he experienced as a child has been severely decimated as a result of unsustainable human practices. Many of the rivers that he fished or swam in have now been completely silted over. Restoration of this childhood wonderland has been a major motivation for his work.

Mugweni's first vocation was as a farm manager on a tobacco, maize and wheat farm. His tenure did not last long as he was soon deeply perturbed by the high input system that temporarily increased production and revenue, but caused severe pollution. He therefore left to become a conservation officer with the government. From 1978 to 1983, he focused on whole-catchment management practices for gully rehabilitation and was later promoted to Agricultural Extension Officer for Buhera in Manicaland province, a severely environmentally degraded region. Faced with this challenge, he initiated catchment rehabilitation projects, one of which won the first Zimbabwe Department of

Natural Resources Parade Conservation Competition. His work triggered a wave of gully reclamation projects in Zimbabwe that dominated the competition between 1986 and

2000.This gully project resulted in a fortuitous set of circumstances that led Mugweni to study agricultural practices in the United States for a year in 1986. While in the US, he visited the pioneer institute on organic farming, the Rodale Institute in Pennsylvania, as well as a host of ranches in the American West and Midwest. His observations in

America and Zimbabwe led him to the idea that the key issue in land management in arid and semiarid lands with particular regard to cattle herding was the recovery period allocated to pastures. When he returned to Zimbabwe, he launched a pilot project.