Carbohydrates

advertisement

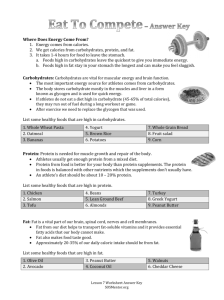

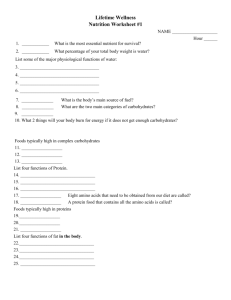

Carbohydrates Carbohydrates are classified as either "simple" or "complex". Some common simple carbohydrates include glucose, fructose, and sucrose, and are typically associated with sweet foods and ripe fruits. The complex carbohydrates are either digestible (starches) or indigestible (fiber). The digestible complex carbohydrates are ultimately "digested" to the simple carbohydrate glucose when they are consumed. While the ultimate "fuel" for muscles is glucose, complex carbohydrates usually carry with them other nutrients, such as B vitamins, which are necessary for muscles to get energy from the foods we’ve eaten. Simple carbohydrates (sugars) on the other hand, do provide energy but may not contain the other nutrients needed to use this energy. Therefore, it is generally recommended that athletes consume no less than 60% of total calories from carbohydrates, and no more than 10% of these calories in the form of simple carbohydrates. Good sources of carbohydrates include pasta, bread, cereal, legumes (beans), fruits, and vegetables. Glycogen is the storage form of glucose, and it is called upon when muscles need more fuel. Glycogen is needed for both endurance and strength events, but the human body has a limited capacity to store it. Therefore, even though athletes need a lot of it we only have a limited supply. Therefore, it is important to take every opportunity to keep this glycogen "fuel tank" full by making carbohydrates a main part of the foods usually consumed, and by eating carbohydrates before, during, and immediately after exercise. Providing a constant supply of carbohydrates is the best, simplest, and safest means of "glycogen loading". Because glycogen is only efficiently stored when an athlete is well hydrated, it is also important to make certain that plenty of fluids are consumed while eating carbohydrates. This is a list of some commonly consumed foods with the distribution of carbohydrate, protein, and fat: (Kcal=Calories) Food Calories % Carbohydrate % Protein % Fat 1 raw apple 84 100 0 0 10 grapes 36 100 0 0 1 cup orange juice 104 96 4 0 1 oz Rice Krispies 108 93 7 0 1 baked potato 148 92 8 0 1 banana 105 89 3 7 1 cup spaghetti with sauce 198 79 1 bagel 198 77 1 slice bread 69 1 oz Cheerios 114 70 12 14 75 9 9 12 14 13 16 Protein Protein is a part of muscles, bone, hemoglobin, myoglobin, hormones, antibodies, and enzymes, and makes up about 45% of the human body. There is no question that it is an important constituent of the diet, but the amount of protein we actually need for activity and health is considerably less than many people think we need. The requirement for protein is dependent on total energy intake, the amount of training an athlete does, and the intensity of that training. Of these factors, the most important one is total energy (calorie) intake. Increasing energy intake from carbohydrate improves protein utilization, while lowering energy intake to a level below the amount needed causes increased protein losses and breakdown. Therefore, one of the best ways to make certain protein status is OK is to make certain enough total energy is consumed to maintain activity and growth requirements. Muscle is approximately 70% water and only about 20% protein. Therefore, increasing muscle mass requires extra water, extra energy in the form of carbohydrates (to maintain the needs of that extra muscle), and a little extra protein. In fact, for an athlete increasing muscle mass at an extraordinarily high rate of 1 kg/week (2.2 lbs of extra muscle per week), only 4 extra ounces of meat per day would be needed. In most surveys that have been done on athletes, protein intake from food far exceeds requirement. The generally accepted athlete requirement for protein is between 1.5 and 2.0 grams per kilogram of body weight. Many studies show that athletes commonly consume well over 3.0 grams per kilogram of body weight. For athletes who take unnecessary protein powders and amino acid supplements, the intake of protein is often higher than 3.5 grams per kilogram of body weight. However, carbohydrate and water intake is typically lower than the amount needed to maintain or increase muscle mass. It also appears that those athletes (body builders, weight lifters, football players, etc) who generally consume supplements of protein and amino acids (components of protein) are those who need supplements the least. High sources of protein include meat, poultry, fish, and eggs. However, vegetarians can obtain adequate protein by combining non-meat items. For instance, combining legumes (beans) and cereals (rice or corn) creates a protein combination of high quality. However, animal proteins provide numerous other nutrients (including iron and zinc) that are more difficult to obtain elsewhere unless the diet is very carefully planned. The bottom line is this: If you consume enough energy from carbohydrates, then the protein you consume will be used for all the valuable protein related functions, such as synthesis and maintenance of muscle, synthesis of creatine, and the creation of hormones and enzymes. However, without enough carbohydrate energy, the consumed protein will be 'burned' as fuel rather than used for these other critical functions. Burning protein as fuel causes increased water loss that can increase the risk of dehydration (a major factor related to poor performance in athletes.) Fat Fat is an energy source that provides the essential fatty acid and carries fat soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, E, and K) . In general, people eat a great deal more fat than is desirable for health or necessary for athletic performance. Americans typically consume foods that provide well over 35% of total calories from fat, and surveys of athletes indicate that their average fat intake is only slightly lower. Athletes should strive to have a fat intake that does not exceed 25% of total calories. To achieve this goal, it is important to know what foods are high in fat and to know some strategies that might make it easier to reduce fat intake. The good news is that, because fat is such a concentrated source of energy, reducing fat intake makes it possible for you to eat much more food! Fats are a natural component of some foods, such as whole milk, meat, nuts, and cheese, and they are often added in food processing to make potato chips, other fried foods, and desserts. Many people don’t realize that whole milk, even though it contains only 3.8% fat by volume, derives over 50% of its calories from fat. Even 2% milk, which is touted as a "low fat" product, derives over 32% of its calories from fat. Skim milk, on the other hand, contains all of the nutrients of whole milk but with NO fat. A simple strategy for reducing fat intake is to follow these three simple rules: Consume little or no fried foods (the baked, broiled, or boiled equivalent is OK). Stay away from prepared meats (bologna, salami, bacon, sausage, etc.). These are typically very high in fat. Limit the consumption of visible fats (butter, margarine, fat surrounding steak, chicken skin, etc.) Fats are metabolized during exercise, but it takes time and aerobic training to become an efficient fat "burner". In addition, excess dietary fat is very efficiently and easily converted to stored body fat. Therefore, a combination of frequent exercise and lower dietary fat are both needed to assure a good body fat level. The good news is you don't have to totally eliminate fat from your diet. Rather, take some simple steps to reduce the fat in your diet. Some 'diets' suggest that increasing fat intake is good for athletic performance. In fact, all the good studies strongly suggest that higher carbohydrate intake and lower fat intake are important for optimizing athletic performance. So, don't be taken in by the fad diets. Eat a reasonably lower fat diet with plenty of carbohydrates to fuel activity. Fluids Water may be the most critical single nutrient needed to ensure that the athlete can perform up to his/her trained or conditioned ability. Since heat production is increased with ALL forms of exercise, it is necessary for athletes to maintain water balance so this excess heat can be dissipated through the production of sweat. With the evaporation of sweat, heat is lost from the blood that circulates near the skin. The rate of sweat loss varies between people and with the temperature, but it is common to see water losses of up to 3 liters (over 6 quarts!) per hour in trained athletes exercising in hot and humid environments. Water losses that represent 6% of body weight may occur with 2 hours of training in high heat. DEHYDRATION occurs when fluid losses are greater than 1% of body weight, and athletic ability is impaired with a 2% loss of body weight. This means a 100 lb athlete who loses 2 pounds during exercise may no longer be performing up to his/her trained ability because of the excessive water loss. Typical symptoms of inadequate fluid intake during exercise include: thirst, fatigue, loss of coordination, mental confusion, irritability, dry skin, elevated body temperature, and reduced urine output. Heat stroke, caused by severe heat injury and inadequate hydration, has a mortality rate of 80%. To assure that an athlete learns to drink sufficient amounts of fluid during exercise, weight should be taken before exercise and after exercise. The difference in weight in pounds is equal to the the amount of fluid, in pints, the athlete should have consumed during exercise. For instance, an athlete losing 4 pounds during exercise should learn to consume 4 additional pints of fluid during that activity. GENERAL GUIDELINES: Adequate daily consumption of fluids to avoid thirst. Limit consumption of caffeine and alcohol containing fluids. They act as diuretics and can increase fluid loss. Drink at least 8 to 16 oz of fluid 2 hours before exercise Drink at least 4 to 8 oz of fluid immediately before exercise Drink at least 4 to 8 oz of fluid every 15 to 20 minutes during exercise (whether thirsty or not) Drink at least 8 to 16 oz of fluid after exercise Drink at least 8 oz of fluid with each meal Drink at least 8 oz of fluid between meals. Note: Sports drinks should be used in place of water, regardless of the length or intensity of the activity. They encourage drinking, and improve the delivery of both carbohydrate and water to the muscles. They also, importantly, help to maintain blood volume. Vitamins and Minerals The following covers b-vitamins, vitamin C, calcium, and iron. There are many other vitamins and minerals of equal importance in human nutrition. These are covered because they are either closely linked to physical activity, or are related to nutrient risks commonly faced by athletes. B-VITAMINS B-vitamins have a well-established role in energy metabolism and muscle function and, because of this role, are frequently taken in supplement form by athletes. These vitamins, which include thiamin (B-1), riboflavin (B-2), niacin, pyridoxine (B-6), folacin, cyanocobalamin (B-12), pantothenic acid, and biotin, work together in energy metabolic processes. Taking supplements, in the absence of a known deficiency, does NOT improve athletic potential, and may introduce harmful side effects. Therefore, a balanced diet is the best approach to making certain you get enough of the B-vitamins. Thiamin Food Sources: Liver, pork, lean meats, wheat germ, whole grains, enriched breads, and cereals. Riboflavin Food Sources: Milk and milk products, liver, enriched breads, and cereals. Niacin Food Sources: Liver, poultry, fish, peanut butter. Pyridoxine Food Sources: Liver, herring and salmon, wheat germ and whole grains, lean meats. Folacin Food Sources: Liver, wheat bran, whole grains, spinach and other green leafy vegetables, legumes, orange juice. Cyanocobalamin Food Sources: Foods of animal origin, specially prepared fermented yeasts, and fortified soy products. Biotin Food Sources: Egg Yolk, liver, and legumes. Pantothenic Acid Food Sources: Eggs, liver, wheat bran, peanuts, legumes, lean meats, spinach, and other vegetables. VITAMIN C Vitamin C is involved in the manufacture of collagen, a connective tissue protein, and is also involved in the manufacture of thyroxin, a hormone that controls the rate at which energy is used. Vitamin C is also involved in the absorption of iron, resistance to infection, and metabolism (breakdown and build-up) of amino acids, the building blocks of protein. It is not clear from studies whether a marginal vitamin C status impairs athletic performance or work capacity. Therefore it does not appear that taking supplements, even when a good diet is consumed, is necessary for optimizing athletic performance. Toxicity symptoms to excessive vitamin C intake are rare. Symptoms of vitamin C deficiency include: Microcytic anemia (small and inadequate red blood cells, limiting oxygen carrying capacity.) Purpura (small red dots appearing at the base of hair follicles, due to hemorrhage.) Easy hemorrhaging Depression Frequent infections Symptoms of vitamin C toxicity (excess) include: Early red-cell breakdown Nausea Frequent urination Abdominal cramps Diarrhea Good Food Sources of Vitamin C include fresh fruits, fruit juices, an vegetables. Bean sprouts are also good sources. CALCIUM While the recommendation for calcium is between 800 to 1,500 mg/day many athletes have an intake that is far less than this amount. Further, there is evidence that the current requirement is actually lower than it should be. These factors, coupled with the fact that exercise increases bone stress, suggest that more athletes should be concerned about their level of calcium intake. Inadequate calcium intake can increase the risk of stress fractures and, if there is inadequate intake during growth, may increase the risk of early osteoporosis (bone disease) later in life. Bones consist of living cells that are constantly changing (just like all other cells in the body). Providing enough calcium helps to assure that the bones will change in a positive direction. Major functions of calcium include: Bone formation and bone strength Nerve impulse transmission Muscle contraction Blood clotting pH control Blood pressure control The following foods contain about the same amount of calcium (297mg) as 8 oz (1 cup) of milk: Cheddar Cheese l.5oz Cottage Cheese 2 cups Yogurt 1 cup Processed Cheese 1.5 slices Ice Cream 1.5 cups Ice Milk 1.5 cups Tofu 8 oz Broccoli 2 cups Collard Greens 1 cup Turnip Greens 1 cup Mustard Greens 1.5 cups Salmon 4 oz Sardines 2.5 oz Orange Juice w/calcium 1 cup Common calcium supplements and elemental calcium concentration: Calcium gluconate 9% calcium Calcium lactate 13% calcium Calcium carbonate 40% calcium IRON Iron deficiency may lower athletic performance because of its involvement in carrying oxygen to cells and removing carbon dioxide. Many athletes may be at risk f or iron deficiency because of poor iron intake, poor iron absorption, loss of iron in sweat, blood loss in the GI tract, and red blood cell breakdown. A condition called "sports anemia" has been reported in athletes, and is most associated with increased red blood cell breakdown and lower hemoglobin concentration when an exercise program is initiated. However, "sports anemia" appears to be a transient condition that disappears when red cell production has an opportunity to catch up to the increased blood volume that occurs with exercise. It appears that female and growing athletes are more at risk for iron deficiency than male or grown athletes. Vegetarian athletes also appear to be at increased risk of deficiency. The following recommendations should help to reduce the risk of iron deficiency: Consume lean cuts of meat (dark poultry or red meat) 3 to 4 times per week. Consume enriched grains and cereals (breads, pastas, etc.) regularly Consume vitamin C containing foods (fruits, fruit juices) with grains and vegetables. The vitamin C enhances iron absorption from these foods. Consume tea, coffee, and all-bran products in moderation. These foods contain substances that may inhibit iron absorption. Women of child-bearing age may require a low-level supplement of iron to assure an adequate intake (consult your physician). Pre-Game Meal In general, the pre-exercise meal should focus on the provision of carbohydrates and fluids. Provision of a nutritionally balanced meal should not be a major concern at this time, especially if the athlete is well-nourished most of the time. There are several goals for the preexercise meal, including: Sufficient Energy - Making certain the athlete obtains sufficient energy to see him/her through much of the exercise/competition that will follow the meal. Inadequate energy may lead to light-headedness, blurred vision, early fatigue, and loss of competitive attitude. Prevent Feelings of Hunger - When the athlete feels hungry, this is a sign that blood sugar may be low. Low blood sugar could impair muscle function and is related to central nervous system fatigue. Drink Fluids - Provision of sufficient fluids to make certain the athlete begins exercise in a fully hydrated state is important for athletic performance and endurance. Eat Familiar Foods - Only consume foods you know make you feel good and don't cause any kind of GI distress. If you're competing in a country you've never been to, there is a big temptation to try unfamiliar local foods. Don't do that until after the competition. Avoid Large Amounts of Raw Fruits and Vegetables - Raw fruits and vegetables may be gas forming, and lead to GI distention and distress. In particular, foods in the cabbage family (cabbage, Brussel sprouts, mustard greens, kholrabi, etc.) appear to be a particular problem. Eating cooked vegatables or fruit juices do not appear to lead to problems. TIMING: There should be adequate time for food to leave the stomach before the initiation of exercise. Because fats cause a delay in gastric emptying, fat in the pre-exercise meal should be kept as low as possible. Ideally, a highcarbohydrate meal should be finished 3.5-4.0 hours before exercise if the meal is large (lots of food); 2.0-3.0 hours before exercise if the meal is small. If fat constitutes more than 25% of total energy in the meal, the timing of the meal should be changed so that it moves further from the time of exercise. Light, carbohydrate snacks (crackers, etc.) may be consume within 1 hour of exercise. Sports beverages may be consumed at any time before and during exercise. Athletes with nervous stomachs may not tolerate food well before exercise or competition, yet they are still in need of energy to fuel their muscles. One solution is to make certain they consume very large amounts of carbohydrates the day before competition, followed by small snacks of carbohydrates and fluids on the day of competition. Some athletes may also tolerate liquid meal replacements well, but these should not be experimented with on a day of competition. SAMPLE PRE-EXERCISE MEAL: (Calories) 2 Cups of Spaghetti (395 calories) 3/4 Cup of Meatless Spaghetti Sauce (203 calories) 2 Tbsp of Parmesan Cheese (46 calories) 3/4 Cup Tossed Salad (1 calorie) 1 Tbsp Low Fat Salad Dressing (67 calories) 2 Dinner Rolls (156 calories) 1 Cup Apple Juice (116 calories) 2 Cups Water (0 calories) Totals: 69% Carbs; 11% Protein; 20% Fat; 1,000 Cal Post-Game Meal Muscles are very receptive to replacing stored muscle energy (glycogen) within the first 1 or 2 hours after exercise because of a high level of circulating enzyme (glycogen synthetase) that aids this process. For those athletes who work out on consecutive days or who have multi-day consecutive competitions, replenishing energy stores immediately after exercise is a good strategy for assuring an optimal energy level on the following day. Also, fluids must be replaced as soon after exercise as possible. Ideally, the athlete should consume 200 to 400 calories from carbohydrates immediately following activity, and then an additional 200-400 calories from carbohydrates within the next several hours. For those athletes who have difficulty eating foods immediately following exhaustive exercise, try high-carbohydrate liquid supplements. These have the added benefit of also providing some needed fluids. Examples of some high-carbohydrate foods: Food Calories % Carbohydrate 1 Bagel 165 76 2 Slices Bread 135 81 1 Cup Pasta 215 81 3 Cups Popcorn 70 79 1 Baked Potato 100 88 1 Apple 80 100 1 Orange 65 100 1 Cup Vegetable Juice 55 93