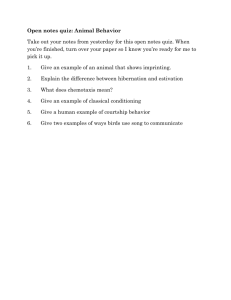

Chapter 35

advertisement

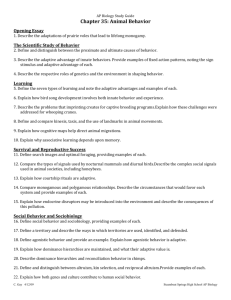

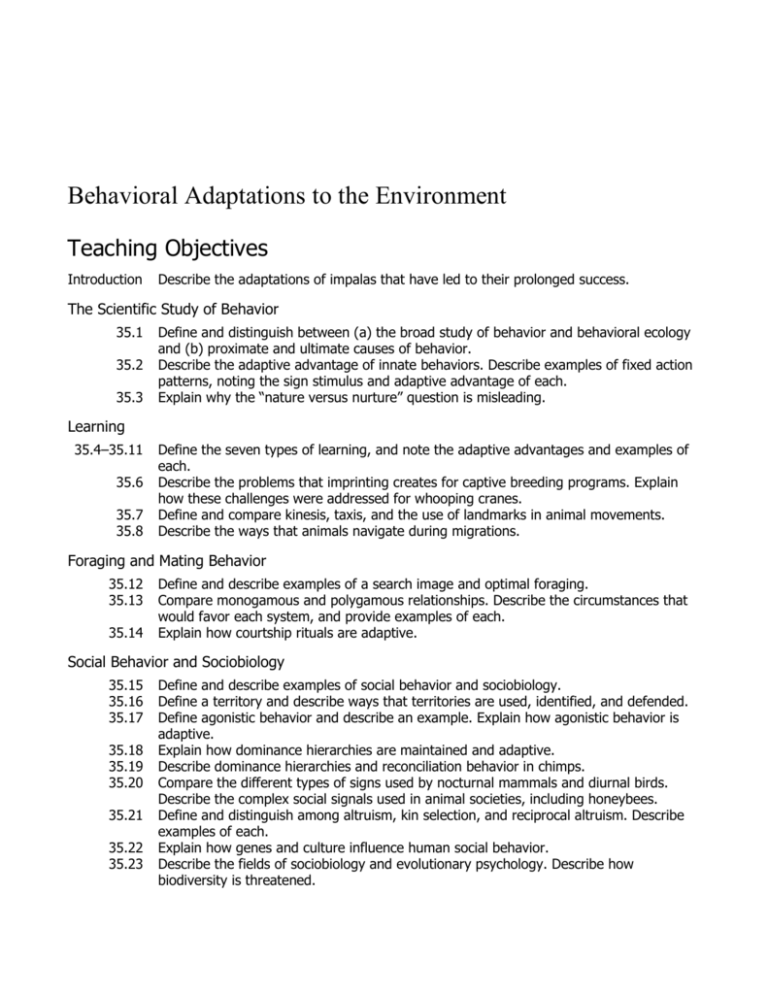

Chapter 35 Behavioral Adaptations to the Environment Teaching Objectives Introduction Describe the adaptations of impalas that have led to their prolonged success. The Scientific Study of Behavior 35.1 35.2 35.3 Define and distinguish between (a) the broad study of behavior and behavioral ecology and (b) proximate and ultimate causes of behavior. Describe the adaptive advantage of innate behaviors. Describe examples of fixed action patterns, noting the sign stimulus and adaptive advantage of each. Explain why the “nature versus nurture” question is misleading. Learning 35.4–35.11 35.6 35.7 35.8 Define the seven types of learning, and note the adaptive advantages and examples of each. Describe the problems that imprinting creates for captive breeding programs. Explain how these challenges were addressed for whooping cranes. Define and compare kinesis, taxis, and the use of landmarks in animal movements. Describe the ways that animals navigate during migrations. Foraging and Mating Behavior 35.12 35.13 35.14 Define and describe examples of a search image and optimal foraging. Compare monogamous and polygamous relationships. Describe the circumstances that would favor each system, and provide examples of each. Explain how courtship rituals are adaptive. Social Behavior and Sociobiology 35.15 35.16 35.17 35.18 35.19 35.20 35.21 35.22 35.23 Define and describe examples of social behavior and sociobiology. Define a territory and describe ways that territories are used, identified, and defended. Define agonistic behavior and describe an example. Explain how agonistic behavior is adaptive. Explain how dominance hierarchies are maintained and adaptive. Describe dominance hierarchies and reconciliation behavior in chimps. Compare the different types of signs used by nocturnal mammals and diurnal birds. Describe the complex social signals used in animal societies, including honeybees. Define and distinguish among altruism, kin selection, and reciprocal altruism. Describe examples of each. Explain how genes and culture influence human social behavior. Describe the fields of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology. Describe how biodiversity is threatened. Key Terms agonistic behavior altruism associative learning behavior behavioral ecology cognition cognitive map communication culture dominance hierarchy fixed action patterns (FAPs) foraging habituation imprinting inclusive fitness innate behavior kin selection kinesis landmarks learning migration monogamous optimal foraging theory polygamous promiscuous proximate questions reciprocal altruism search image sensitive period sign stimulus signal social behavior social learning sociobiology spatial learning taxis territory trial-and-error learning ultimate questions Word Roots agon- 5 a contest (agonistic behavior: a type of behavior involving a contest of some kind that determines which competitor gains access to some resource, such as food or mates) kine- 5 move (kinesis: a change in activity rate in response to a stimulus) socio- 5 a companion (sociobiology: the study of social behavior based on evolutionary theory) Lecture Outline Introduction Leaping Herds of Herbivores A. The impala is a small, graceful grazer of the African grassland. It has not changed in more than 8 million years, yet it is the most successful and most commonly preyed upon animal of the savanna. B. Behavior is the key to the impala’s success. It will form large herds when food and water are plentiful, disperse during drought, warn others of its kind when predators are near, and allow other impalas or birds (the oxpecker) to remove blood-sucking ticks from its face and ears. Impalas will eat almost any vegetation and can go days without water. C. The study of animal behavior is essential to understanding animal evolution and ecological interactions. I. The Scientific Study of Behavior Module 35.1 Behavioral ecologists ask both proximate and ultimate questions. A. Behavior refers to any observable activity that an animal performs. B. Early workers in the field of behavioral biology were von Frisch, Lorenz, and Tinbergen, all Nobel laureates. 1. Von Frisch pioneered the use of experimental methods in behavior, studying food hunting by honeybees. 2. Lorenz, the “father of behavioral biology,” compared behaviors in various animals and found that different stimuli often elicited different behavior. 3. Tinbergen studied the relationship between innate (genetically programmed) behavior and learning. C. Tinbergen is best known for his paper in which he proposed that to fully understand any behavior, one must consider both the mechanism underlying the act and its evolutionary significance. This approach is known as behavioral ecology, the study of behavior from an evolutionary approach. D. Behavioral ecologists ask two levels of questions when observing behavioral activity. The proximate question focuses on the behavior in terms of immediate activities triggered by environmental stimuli (asks the question “how”). The ultimate question focuses on the evolutionary context of the behavior (asks the question “why”). Module 35.2 Early behaviorists used experiments to study fixed action patterns. A. Fixed action patterns (FAPs) are a type of innate behavior, which is behavior performed the same way by all members of a species. FAPs are essentially unchangeable behavioral sequences that can be performed only as a whole and, once started, must be completed (ABC’s?). The stimulus that triggers an FAP (i.e., is the proximate cause of the behavioral sequence) is called a sign stimulus. B. For example, the graylag goose exhibits an FAP when she retrieves an egg that rolls out of her nest. She stands up, extends her neck, and sweeps her head from side to side, using her beak to bring the egg back. If an experimenter moves the egg aside while it is being brought back, the goose will continue the behavior (without the head swinging) until she sits down in the nest again, at which time she will notice that the egg is still outside (Figure 35.2). C. FAPs are particularly important in animals with life spans too short to allow for learning and in newborn vertebrates, where, in the context of the ultimate question, such behavior ensures that the young will obtain food from the parents (or directly from the environment) without any learning. D. FAPs can be discussed in a behavioral ecology context when considering that inappropriate behaviors lead to death and only genes that promote appropriate behavior are passed on to the next generation. Module 35.3 Behavior is the result of both genes and environmental factors. ALL BEHAVIOR IS NEED DRIVEN. A. The relationship between genes and behavior is complex. Most genetically programmed behaviors have some aspect that can be changed by experience. How much behavior is governed by genes and how much by experience is a classic debate. B. Both genes and the environment influence behavior. The question is the relative influence of each over any trait, including behavioral ones. The prairie vole and the mountain vole vary in their behavior after mating and after the birth of their pups. The female prairie voles also have different levels of oxytocin than the female mountain voles do. Similarly, the male prairie vole has increased levels of vasopressin compared to the male mountain vole (Figures 35.3A and B). C. Genetic studies were done to test the effect of inserting the prairie vole gene for vasopressin in mice. The results of the study indicate that the gene for vasopressin was responsible for the observed behavior of the mice that was similar to the prairie vole. D. A cross-fostering experiment was done with mice that were either aggressive or not aggressive. Those that came from the aggressive species were placed in the nonaggressive nest and vice versa. The behaviors observed indicated that aggression was a learned behavior. E. The complementary results of these studies indicate that behavior is a combination of both genetics and environmental factors. Men vs. Women. Enviroment Men vs. Women. (Rape, “Stud” vs. “Slut” ( Male vs. female teachers having sex with students etc… ) Pregnancy Monthly cycle Eggs vs. sperm Reproductive age limits Bucks fighting for the right to breed with the entire herd. Re-population of earth…1 woman / 1000 men vs. 1 man / 1000 women. Etc… II. Learning Module 35.4 Learning ranges from simple behavioral changes to complex problem solving. A. Learning is modification in behavior resulting from specific experience. The different types of learning reflect the complexity of the changed behavior (Table 35.4). Learning empowers animals to change their behavior in response to environmental changes. B. Habituation happens when an animal learns not to respond to an unimportant stimulus. This is one of the simplest forms of learning and is common in all animals. i.e. Barking dog, scare crow. It is highly adaptive because it prevents animals from wasting energy on pointless activity. For example, if a hydra is repeatedly touched, it will eventually stop contracting (the normal response). C. Habituation increases fitness because it focuses the energy expended by an animal on survival and reproduction. Module 35.5 Imprinting is learning that involves both innate behavior and experience. A. Imprinting is learning to perform a response during a limited time period, and the learned behavior is irreversible. The sensitive period is the limited time when an animal must learn. Its learned component is the imprinting itself. Imprinting is particularly important in the formation of bonds between animals. Humans imprinting years 13-18 APPROX B. Lorenz’s most famous study showed that graylag goslings would imprint on him as a mother figure if, during the first two days after hatching, the geese saw him and not the mother. The specific imprinting stimulus was found to be the movement of an object (normally the parent) away from the hatchlings (Figure 35.5A). C. Salmon imprint on the complex of odors unique to the stream they hatch in so that, as adults, they can return to that same stream to spawn (Chapter 29, Opening Essay). D. Each species of songbird has its own unique song. Song imprinting occurs in birds learning the mating call of each species. During a critical period of 10–50 days after hatching, a bird imprints on the calls of its own species (Figure 35.5B). E. Birds raised in isolation who do not hear their species’ song until after 50 days do not learn to sing normally, whereas isolated males played tapes of their species’ song during the critical period do learn to sing normally. F. Studies of the white-crowned sparrow demonstrate that there is a genetic component to their song. Isolated males who were exposed to the songs of species other than their own did not learn those songs; rather, they sang an abnormal song. G. Humans have a sensitive period for learning vocalization. Children are much better at learning a foreign language than adults. Module 35.6 Connection: Imprinting poses problems and opportunities for conservation programs. A. Breeding endangered animals in captivity in an effort to increase their chance of survival is a difficult task due to problems related to imprinting. B. If the parents are available after birth, imprinting is less of a problem. However, if the parents are not available, proper imprinting is limited. C. An imprinting experiment with a whooping cranes recovery project required the use of a lightweight plane. The plane was to become the surrogate mother and eventually lead the young birds on their first migration to Florida (south for the winter). D. The program was successful; the young whooping cranes bonded with the plane (as mother) and migrated to Florida for the winter. Subsequent trips have led several more generations to Florida, and the whooping crane count is approximately 300 birds in the wild. Module 35.7 Animal movement may be a simple response to stimuli or behavior with a response. A. Kinesis is a random movement in response to a stimulus. The activity is repeated until the organism finds itself in a more favorable environment. Human body lice are more active in dry areas and less active in wet areas. B. Orientation behavior involves directed movements toward (positive) or away from (negative) a stimulus. Such directed movement is known as taxis. Numerous taxes are named from the stimuli that elicit the behavior (photo-, geo-, chemo-, rheo-). Thus, positive rheotaxis is exhibited by fish swimming upstream (Figure 35.7A). Taxis is a more efficient behavioral response than kinesis. NOTE: Even prokaryotes and protists exhibit kinetic and taxic behaviors. Distinguish between a taxis (movement) and a tropism (growth) (as seen in plants; Module 33.9). C. Landmarks are used by animals to find their way from place to place, and each animal must learn the particular landmarks that are unique for that location (Module 35.7B). The capacity to learn by landmarks is called spatial learning and is an advantage when navigating through an environment. Module 35.8 Movements of animals may depend on internal maps. A. Animals use cognitive maps, internal representations of spatial relationships, to navigate through the environment. The most extensive studies of cognitive maps have been made of animals that undergo seasonal migration. B. The family of birds including jays, crows, and nutcrackers use cognitive maps to store and then retrieve their cache. C. Seasonal migration is the regular movement from one place to another during a particular time of the year. Animals usually migrate to areas that are more suitable for feeding or reproducing. D. Gray whales migrate north in summer to rich feeding grounds on the coast of Alaska, and south in winter to shallow lagoons off Baja California (Mexico), where they breed and produce offspring before the next northward migration. They have been shown to use coastal landmarks for orientation. Preview: The impact of human activities on migration and dispersal is discussed in Chapter 38. E. Insect-eating birds winter in the tropics and summer at high latitudes. Many have been shown to navigate using the positions of stars and the sun. Unless birds use the North Star as a fixed landmark, such navigational skills require that the animals internally adjust their sensors to take into account the daily changes in direction of stars and the sun (Figure 35.8). F. Some maps used by animals are purely genetic. The monarch butterfly migrates thousands of kilometers to a place it has never been. Module 35.9 Animals may learn to associate a stimulus or behavior with a response. A. Associative learning is learning that a particular stimulus, or behavioral response, is linked to a reward or punishment. B. Classical conditioning is producing a behavioral response when a reward or punishment is associated with an arbitrary stimulus. Eventually the response is elicited without the reward or punishment (B. F. Skinner). C. Natural associations occur by trial-and-error learning, where, over time, an animal associates the positive or negative results of a certain type of behavior with the reward or punishment it brings (Figure 35.9). Module 35.10 Social learning involves observation and imitation of others. A. Social learning is learning by observing the behavior of others. Predatory behaviors are passed from mother to young by observing the hunting habits exhibited by the mother. B. The vervet monkey is another good example of learned behavior and the different (correct) calls that are used for various types of communication (Figure 35.10). Module 35.11 Problem-solving behavior relies on cognition. A. Cognition is the ability of an animal’s nervous system to perceive, store, process, and use information provided by the senses. The ability to think or problem solve occurs mostly in primates, dolphins, and some birds. B. Dogs solve problems by trial and error or by remembering a prior experience, not by thinking (as is seen in chimpanzee behavior) (Figure 35.11A). C. Some birds, such as ravens, demonstrate the capacity to solve problems (Figure 35.11B). III. Foraging and Mating Behaviors Module 35.12 Behavioral ecologists use cost-benefit analysis in studying foraging. A. Foraging is the food-obtaining behavior that includes recognizing, searching for, securing, and eating food. B. Some animals are feeding generalists. For example, the gulls will eat many foods. While other animals are feeding specialists such as the koalas, which eat only eucalyptus leaves (Figures 35.12A and B). Most animals can be classified somewhere in between these two extremes. An animal is said to have a search image when it concentrates on feeding on an abundant food item to the exclusion of other food. C. Optimal foraging theory states that feeding behavior should provide maximum energy (or nutrient) gain for minimum energy and minimal time of exposure to predators. D. Optimal foraging depends on the animal’s compromising among a number of trade-offs involved with choosing one feeding-behavior pattern over another. Different foods have different digestibilities. Further, prey differ in their relative sizes, population densities, and ease of capture, and these factors may change through time. Searching for one type of food might expose an animal to more predation. Natural selection causes animal behavior to evolve in a direction that optimizes foraging over the entire range of possible environments and preys the animal could forage for. An animal may switch foraging behaviors, depending on conditions. Module 35.13 Mating behaviors enhance reproductive success. A. Mating behaviors that improve the chance of passing on genes to the next generation are selected for. There are three common mating systems that are used by animals: 1. In promiscuous mating, no strong bonds or committed relationship is formed. 2. In monogamous mating, mates remain together for an extended period of time. 3. In polygamous mating, one individual mates with several different individuals. B. Examining the habits of a given species and the needs of the young will explain the mating system used by the species. Birds provide a good example of the mating system used based on the needs of the young. Many birds are born very helpless and require large amounts of food. This requires the efforts of a mating pair (monogamous system). However, if the young chicks are born and can quickly forage for themselves, the need of two parents is diminished (e.g., pheasants and quail) and a polygamous system is used. C. Certainty of paternity is a factor that can influence mating behavior. If the act of fertilization is internal and there is a significant time lapse before birth or egg laying occur, the certainty of the father is in question. The male jawfish fertilizes the eggs then sucks the eggs into its mouth to care for the eggs that were certainly fertilized by its sperm (Figure 35.13). Module 35.14 Mating behavior often involves elaborate courtship rituals. A. Courtship rituals signal that certain individuals are not threats to others but are the correct species and sex and are physically fit for mating. B. Courtship rituals often contain actions that signal appeasement. For example, all loon courting behavior consists of appeasement gestures. During their courtship, loons turn their heads away, dip beaks, and submerge heads and necks, and the male turns his head backward and down as a final invitation to land to mate (Figure 35.14). C. Many other animals go through group courtship rituals. Sage grouse males congregate in a lek, an area where they strut in front of watching females. All the females choose among all the males, usually mating with only a few of the most dominant individuals. If there is a positive correlation between a male’s display and his evolutionary fitness (as behavioral ecologists think), such behavior will give a female the best chance at passing on her genes (Module 13.17). IV. Social Behavior and Sociobiology Module 35.15 Sociobiology places social behavior in an evolutionary context. A. Social behavior is broadly defined as any interaction between two or more animals, usually of the same species. Much of social behavior is highly adaptive because it can affect the growth and regulation of populations. B. Many social behaviors involve interactions between two or more individuals. Courtship, aggression, and cooperation have social elements. A key element of all types of social behavior is some form of communication. C. The research discipline that focuses on the adaptive advantage of social behavior and how certain behaviors are preferentially selected over others through natural selection is called sociobiology. Module 35.16 Territorial behavior parcels space and resources. A. A territory is an area, usually fixed in location, inhabited by an individual and defended from occupancy by other individuals of the same species. The sizes of territories depend on species, use, and the total size of the area out of which the territories are parceled. Not all animals are territorial. Preview: Population distribution patterns, some that are a result of territoriality, are discussed in Module 37.2. B. When space is at a premium, breeding birds maintain tiny nesting territories by agonistic behavior (Figure 35.16A). C. Large hunters defend much larger territories for hunting and mating activities. They maintain—and spend considerable time proclaiming—their territorial boundaries, either by calling (birds, sea lions, squirrels) or marking (defecation by jaguars, scent marking by cheetahs and other cats) (Figure 35.67B). Marked territories reduce undesirable confrontations. D. Territorial animals gain exclusive use of the resources in their territories, gain familiarity with one area, and are better able to raise young without interference from other individuals. Module 35.17 Rituals involving agonistic behavior often resolve confrontations between competitors. A. Agonistic behavior includes behavior that settles disputes among members of populations through displays or actual combat. It may involve tests of strength, posturing, or ritualized contests (Figure 35.17). B. In most cases, agonistic behavior ends when one individual stops threatening, becomes submissive, and enters into some kind of surrender behavior. Further aggressive activity is inhibited. C. Agonistic behavior is adaptive because the inhibition of aggressive activity minimizes the potential for damage that could adversely affect the reproductive success of both individuals. Module 35.18 Dominance hierarchies are maintained by agonistic behavior. A. The pecking order established among hens in a hen yard is an example of a dominance hierarchy, the rank among individuals based on social interaction. No hen will peck the alpha (top-ranked) hen, while all other hens will peck the omega hen (lowest-ranked). The alpha hen gets first access to resources such as food, water, and nesting sites (Figure 35.18). B. In a dominance hierarchy, the position of each animal is fixed for extended periods of time. By establishing the set pattern, the animals in the social group do not need to constantly waste energy testing each other’s status and can devote their energies to other activities such as finding food, watching for predators, locating a mate, and caring for young. C. Dominance hierarchy is a common social behavior among vertebrates. The wolf pack has an alpha (dominant female) that controls breeding based on resources. Module 35.19 Talking about Science: Behavioral biologist Jane Goodall discusses dominance hierarchies and reconciliation behavior in chimpanzees. A. Dr. Jane Goodall has studied chimpanzees in their natural habitat in eastern Africa since the early 1960s (Figure 35.19A). She promotes better understanding of primate behavior and pushes for better living conditions for animals kept in zoos or medical research laboratories. B. The closest living relatives of humans are chimpanzees. Dominance hierarchies are an important part of chimpanzee life. Adult males expend considerable effort improving or maintaining their social status, often by using agonistic charging displays. Higher-ranked males have preferred access to the best food, resting places, and mates, but other behaviors provide complex solutions to many social conflicts that do not always end with the dominant male having all the advantages (Figure 35.19B). C. Females develop a different hierarchy. High status allows them to use the best food items. A high-ranking female’s offspring start out in their social groups with higher social rankings. D. Reconciliation behavior has adaptive advantages. The family group of chimps must cooperate to survive. So when tensions are high among members of the family, some gesture of reconciliation is offered to calm the situation (Figure 35.16B). Goodall states that the single most important social behavior is grooming. It improves bad relations and maintains good ones. Maybe we can learn something from our primate cousins! E. Goodall’s research has led her to conclude that chimpanzees are conscious. Module 35.20 Social behavior requires communication between animals. A. A signal is used by an animal, according to behavioral ecologists, to communicate with and elicit a change of behavior in another animal. The signals used may be sounds, odors, visual displays, or touches. In general, the more complex the social organization of a species population, the more complex the signaling needed to maintain it (Figure 35.20A). B. The types of signals used by a species are determined by the lifestyle. Nocturnal animals use sound and odor, while diurnal animals use sound and sight, to communicate. C. Aquatic animals also use signals. Erect fins ward off intruders, and electrical signals indicate hierarchy or status. Whales communicate with their songs, which can be heard many kilometers away and are used to locate each other. D. Social insects exhibit some of the most complex social systems. A colony of honeybees includes more than 50,000 individuals, mostly sterile workers that maintain the health of the hive by feeding, caring for young, and doing defensive behaviors. Pheromones released by the queen bee help maintain social order. Other pheromones can signal the need for aggressive or defensive behavior. Feeding activities, in particular, involve complicated communication to pass on the locations of food sources. E. Von Frisch first described the signaling system, hypothesizing that two types of behavior signaled two types of food. Signaling in the dark hive mostly involves physical contact and sound. F. “Round dances” indicate that food is near. “Waggle dances” indicate the distance and direction of the food. The waggle’s speed indicates distance, and the angle relative to the hive’s vertical position indicates direction relative to the horizontal position of the sun (straight up is equivalent to flying directly toward the sun). An internal clock must also be involved because the bees maintain their sense of where the food is even if several hours of sunless storm interrupt feeding (Figure 35.20B). Module 35.21 Altruistic acts can often be explained by the concept of inclusive fitness. A. Altruism is behavior that reduces an individual’s fitness while increasing the fitness of a recipient. For example, naked mole rats have a social structure resembling that of honeybees. The queen mates with three males (kings), while the rest of the colony consists of nonreproductive males and females who care for the queen and kings (Figure 35.21A). NOTE: The example given of altruistic behavior in honeybee hives is a special case. In a sense, the whole hive is one individual with adaptive behavior among its parts. The hive is composed of one reproductive queen and thousands of sterile workers. The workers function like cells of other organisms, where the loss of one is not missed by the whole. B. At first glance, altruism seems nonadaptive. However, it is thought to have evolved by either of two mechanisms: kin selection or reciprocal altruism. C. A Belding’s ground squirrel will sound an alarm to warn other squirrels that a predator is near. This is not good for the individual that sounds the alarm because it reveals its location to the predator (Figure 35.21B). The idea of helping others (a relative) pass on their genes instead of passing on their own genes is called inclusive fitness. D. Kin selection states that altruistic behavior would evolve in groups of related individuals because it increases the number of copies of a gene common to the whole group. For example, the great majority of the individuals in a naked mole rat colony are closely related. The queen appears to be either a sibling, daughter, or mother of the kings; the nonreproductive individuals are either the queen’s direct descendants or her siblings. Hence, by promoting the reproductive success of the queen and kings, the nonreproductive individuals are increasing the probability that copies of their own genes will be represented in the next generation. E. Reciprocal altruism is an altruistic act repaid at a later time by the beneficiary of the act (or social associates of the beneficiary). For instance, chimpanzees will sometimes save the life of a nonrelative. If a future “repaying in kind” always (or usually) follows, the altruistic behavior increases the fitness of an individual in the long run. Module 35.22 Connection: Both genes and culture contribute to human social behavior. Review: The evolution of human culture (Modules 19.9–19.12). A. Group behavior, like individual behavior, has genetic and environmental components. Culture is a component of the environment and is defined as a system of information transfer through social learning or teaching that influences the behavior of individuals in a population. B. A recent study published by the National Academy of Sciences in 2003 sought to answer the question “Do opposites attract?” (Figure 35.22). Almost 1,000 heterosexual men and women were asked to rank ten attributes based on importance of choosing a long-term partner. They were then asked to evaluate themselves on these same attributes. Results from the study refute the old adage and indicate that “likes attract.” C. Just as the genetics of a population will evolve over time, social behavior evolves. Module 35.23 Talking about Science: Edward O. Wilson promoted the field of sociobiology and is a leading conservation activist. A. Dr. E. O. Wilson’s 1975 book, Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, promotes the idea that social behavior is genetically based and undervalued in the scientific study of social behavior (Figure 35.23). Most of the book deals with nonhumans; however, two chapters discuss humans. This book rekindled the old debate about which most strongly influences human behavior: genes (nature) or learning (nurture). B. In the 25th anniversary edition of Sociobiology, Wilson explains that research in the areas of neurobiology and human genetics improves our understanding of human behavior. A new field of research has emerged from sociobiology called evolutionary psychology. Another area of research that is becoming increasingly important for society is evolutionary biology. C. In a more recent book, The Diversity of Life, Wilson discusses a “biodiversity ethic.” This ethic holds that humans should never knowingly allow a species to go extinct if measures to save it can be implemented. He holds that biodiversity has an inherent value to humans apart from the physical welfare it provides. D. In Wilson’s latest book, The Future of Life, he describes the intrinsic value of biodiversity and explains that it makes good economical and ethical sense to preserve all forms of life. The cause of the current biodiversity crisis, according to Wilson, is a result of two factors: 1. The population explosion. 2. The ever-increasing demand for energy. E. One thing that may help this crisis is the education and empowerment of women. As women become better educated, they choose to have children at a later stage in life, which postpones the next generation and reduces the birth rate. Preview: Human impact on the biosphere (Chapter 38). Class Activities 1. Demonstrations of behavior are the clearest way to describe and explain the principles. Although social behaviors (other than those of students) are difficult to demonstrate in a classroom, individual types of behavior can sometimes be shown, particularly by animals 2. 3. that are familiar with their laboratory homes. In small classrooms or laboratory settings, reptiles and fish will show territorial, agonistic, and mating behaviors. Animals often follow chemical trails. Markers with various odors can be purchased at relatively low cost. These markers can be used to create a chemical trail that can be followed by blindfolded students. It is interesting to compare how well such trails are followed by females relative to males, smokers relative to nonsmokers, those with allergies relative to those without allergies, etc. As college students your students will definitely be interested in an examination of human mating behaviors. Assign your students to groups to research such mating behaviors in different human cultures. Transparency Acetates Figure 35.2 A graylag goose retrieving an egg—a fixed-action pattern Table 35.4 Types of learning Figure 35.7A Positive rheotaxis of a trout Figure 35.7B Nest-locating behavior of the digger wasp Figure 35.8 An experiment demonstrating star navigation Figure 35.14A Courtship and mating of the common loon Reviewing the Concepts, page 724: Innate behavior: fixed action patterns (FAPs) Reviewing the Concepts, page 724: Imprinting Connecting the Concepts, page 724: Behavioral ecology Media See the beginning of this book for a complete description of all media available for instructors and students. Animations and videos are available in the Campbell Image Presentation Library. Media Activities and Thinking as a Scientist investigations are available on the student CD-ROM and website. Animations and Videos Module Number Ducklings Video Chimp Cracking Nut Video Albatross Courtship Video Blue-Footed Boobies Courtship Video Giraffe Courtship Video Snake Ritual Wrestling Video Wolves Agonistic Behavior Video Chimp Agonistic Behavior Video 35.5 35.11 35.14 35.14 35.14 35.17 35.17 35.18 Activities and Thinking as a Scientist Module Number Web/CD Thinking as a Scientist: How Can Pillbug Responses to Environments Be Tested? 37.7 Web/CD Activity 37A: Honeybee Waggle Dance 37.20 ## Instructor’s Guide to Text and MediaChapter 35 Behavioral Adaptations to the Environment ## Instructor’s Guide to Text and MediaChapter 35 Behavioral Adaptations to the Environment ## Instructor’s Guide to Text and MediaChapter 35 Behavioral Adaptations to the Environment ## Instructor’s Guide to Text and MediaChapter 35 Behavioral Adaptations to the Environment ## Instructor’s Guide to Text and MediaChapter 35 Behavioral Adaptations to the Environment ## Instructor’s Guide to Text and Media