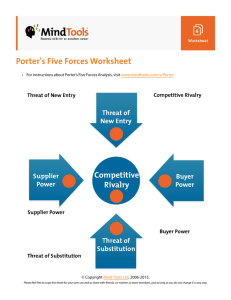

Michael Porter and Porterism

advertisement