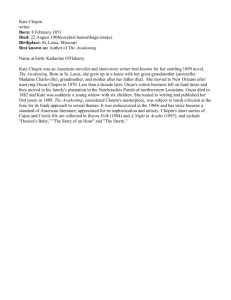

Chopin on his Creative Process An early letter by Chopin mentions

advertisement

Chopin on his Creative Process An early letter by Chopin mentions that he was meeting with his teacher, Joseph Elsner, 1769 – 1854, six hours a week for lessons in “strict counterpoint.”1 He apparently went to Vienna for further study but no one wanted to teach him, one prospective teacher saying that he was surprised that he had learned so much in Warsaw. Chopin answered that even a donkey could learn from Elsner.2 In another early letter Chopin again gave credit to his old teacher. If I had not been taught by Elsner, who imbued me with convictions, I should doubtless have accomplished still less than I now have.3 Chopin was concentrating on becoming a pianist when he was in Paris in 1831. He had initial lessons with Friedrich Kalkbrenner, 1785 – 1849, who wanted a commitment for three years study. An interesting letter to his old teacher, Elsner, gives an interesting biographical sketch of Chopin at this critical time. Here and there in Germany I am known as a pianist; certain musical papers have spoken of my concerts raising hopes that I shall shortly be seen taking rank among the first virtuosi of my instrument.... Today only one possibility offers for the fulfillment of this promise; why should I not seize it? In Germany I could not have learned the piano from anyone for though there were persons who felt that I still lack something, no one knew what.... Three years with Kalkbrenner are a long time; too long. Even Kalkbrenner admits that, now that he has examined more closely.... But I would be willing to stick to it for three years if that will only enable me to take a big step forward in what I have undertaken. I understand enough not to become a copy of Kalkbrenner. Nothing will interfere with my perhaps overbold but at least not ignoble desire to create a new world for myself....4 1 Letter to Jan Bialoblocki, Warsaw, Nov. 2, 1826. Letter to his family, Vienna, August 19, 1829. 3 Letter to Tytus Wojciechowski, Warsaw, April. 10, 1830. 4 Letter to Joseph Elsner, Paris, Dec. 14, 1831. 2 1 The reader should be reminded that Chopin dedicated his first piano concerto to Kalkbrenner. Regarding his composition, Chopin rarely discussed the nature of his inspiration, but one hint in an early letter suggests that his ideas rarely came easily. For the last week I have written nothing either for men or for God.... I very seldom get an idea like the one that came to my fingers so easily one morning on your piano.5 Perhaps the most valuable insight comes to us second-hand from Liszt, who overheard Chopin respond to a lady who asked about the source of his emotions. Regardless of my transient joys, I am never free of a feeling of melancholy which somehow forms the base of my heart.6 Chopin mentioned this word again in a rare description of the specific emotions he was feeling in the “Adagio” of his first piano concerto. The Adagio of the new concerto in E minor is not meant to be loud, it’s more of a romance, quiet, melancholy. It should give the impression of gazing tenderly at a place which brings to the mind a thousand dear memories. It is a sort of meditation in beautiful spring weather, but by moonlight.7 By 1848, a year before his death, Chopin suggested that the creative ideas were not coming. Of musical ideas there can be no question; I am utterly out of the running and make on myself the impression of an ass at a masquerade, or rather a violin’s E string on a bass viol: astonished, tricked, knocked off balance....8 Chopin left a few insights to his actual compositional process. An early letter mentions the importance of being in the mood and of getting the beginning right. The Rondo of the new concerto is not finished, and for that one must be in the mood. I am not even hurrying with it, because once I’ve got the opening Allegro I don’t worry about the rest.9 5 Letter to Tytus Wojciechowski, Warsaw, Dec. 27, 1828. Quoted in Edward N. Waters, Frederic Chopin (London: Collier-Macmillan, 1963), 79. 7 Letter to Tytus Wojciechowski, Warsaw, May 15, 1830. 8 Letter to Auguste Franchomme, Edinburgh, Aug. 6, 1848. 9 Letter to Tytus Wojciechowski, Wassaw, May 15, 1830. 6 2 His correspondence offers a few more hints on his compositional process, including the need for a piano for composition,10 that he loves the labor of writing11 and that he has difficulty composing in Winter.12 For anyone who studies the piano compositions of Chopin it is immediately clear that he had an early tendency to want to leave behind the old classical forms. He mentions this in a charming early letter. As I have no established reputation as yet, the musicians of Breslau admired and feared to admire. They could not make out whether the compositions were good, or whether they only thought they were good. One of the local connoisseurs came up to me and praised the novelty of the form, saying that he had never before heard anything in that form. I don’t know who he was, but he was perhaps the one who understood me best.13 The one thing that is clear with regard to Chopin’s compositional process is that he placed great importance on the ability to criticize one’s own efforts. He credits his old teacher, Elsner, for forming this part of his discipline. To be a great composer, one must have enormous knowledge, which, as you have taught me, demands not only listening to the work of others, but still more listening to one’s own work.14 One can see this honest self-evaluation even at a very early date in his comment about his Introduction and Polonaise in C Major, “there is nothing in it but glitter; a salon piece for ladies.”15 Chopin found Time to be a necessary element of good self-criticism. He writes his family, When one does a thing, it appears good, otherwise one would not write it. Only later comes reflection and one discards or accept the thing. Time is the best censor and patience a most excellent teacher.16 He makes this same point in another letter in which he compares compositions to children: when they are young they always seem good to the parents.17 And again 10 Letter to Juljan Fontana, Palma, Dec. 14, 1838. Undated letter to Fontana. 12 Letter to his family, Nohant, Oct. 1, 1845. 13 Letter to his family, Breslau, Nov. 9, 1830. 14 Letter to Elsner, Paris, Dec. 14, 1831. 15 Letter to Tytus Wojciechowski, Warsaw, Nov. 14, 1829. 16 Letter to his family, Nohant, Oct. 11, 1846. 11 3 regarding his Impromptu in F sharp major, he worries that it may be poor, “I don’t know yet, it’s too new.”18 One finds this hesitancy, given the lack of the perspective of time, even in the case of one of his last works, his Cello Sonata in G minor. Sometimes I am satisfied with my violoncello sonata, sometimes not. I throw it into the corner, then take it up again.19 Finally, as a matter of completing the record, there is the problem of publication. Publishers represented a basic worry for all the early great composers; Mozart personally proof-read when possible to guard against errors, Beethoven raged at publishers because of errors and in the case of Chopin it was a constant worry that he was being cheated financially. He mentions the important Vienna publisher, Haslinger, in 1830. Haslinger is shrewd. He wants to put me off, courteously but lightly, so that I may give him my compositions for nothing.... Pay, beast!20 The most striking characteristic of Chopin’s correspondence dealing with publication is an apparent hostility toward Jewish publishers. At letter of 1839 gives instructions to a friend for selling some of his manuscripts. Get 500 for the ballade from Probst, and then take it to Schlesinger. If I have got to deal with Jews, let it at least be Orthodox ones. Probst may swindle me even worse, for he’s a sparrow whose tail you can’t salt. Schlesinger has always cheated me but he has made a lot out of me and won’t want to refuse another profit. Be polite to him because the Jew likes to pass for somebody.21 The following week Chopin writes his friend again and he is even more excited. Pleyel’s a fool and Probst a rascal.... No doubt you have received my long letter about Schlesinger. Now I wish, and beg you, give my letter to Pleyel (who finds my manuscripts too expensive). If I have to sell them cheap I would rather let it be to Schlesinger than search for impossible new connections. As Schlesinger can always count on England, and as I am finished with Wessel, let him sell them to whom he likes. The same with the Polonaises in Germany, for Probst is a sly bird; I know him of old. Let Schlesinger sell to whom he likes, not necessarily to Probst. It’s nothing to me. He adores me, because he’s skinning me. Only have a clear 17 Letter to Juljan Fontana, Nohant, August, 1839. Letter to Juljan Fontana, Nohant, Oct. 10, 1839. 19 Letter to his family, Nohant, Oct. 11, 1846. 20 Letter to his family, Vienna, Dec. 1, 1830. 21 Letter to Juljan Fontana, Marseilles, March 13, 1839. 18 4 understanding with him about the money and don’t give up the manuscripts except for cash. I will send Pleyel a receipt. The fool, can’t he trust either me or you? Good Lord, why must one have dealings with scoundrels! Well, I prefer to do business with a real Jew. And Probst is a rascal to pay me 300 for the mazurkas! Why, the last mazurkas brought me 800 at the first jump.... I would rather sell my manuscripts for nothing as in the old days, than have to bow and scrape to such fools. And I’d rather be humiliated by one Jew then three.... Scoundrels, scoundrels....22 A month later he describes his publishers as “Germans, Jews, rascals, scoundrels, offal, dog-hangers, etc.”23 We suspect that getting accurate publications was as difficult as with all earlier composers. Chopin seems exhausted when he writes the publisher, Schlesinger, In the Impromptu which you have published in the Gazette municipale of June 9 the pages are wrongly numbered, which renders my composition incomprehensible.24 22 Letter to Juljan Fontana, Marseilles, March 17, 1839. The reader sees here the fact that there was nothing resembling the modern copyright rights. The same work would be sold in different countries, even in the same town, in editions by different publishers. Confusion still reigns somewhat. The last time we checked one could arrange and perform a work by Stravinsky in the United States, but the same arrangement could not be performed in Canada. 23 Letter to Juljan Fontana, Marseilles, April 25, 1839. 24 Letter to Maurice Schlesinger, Nohant, July 22, 1843. 5