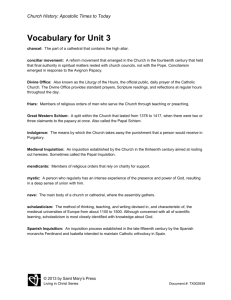

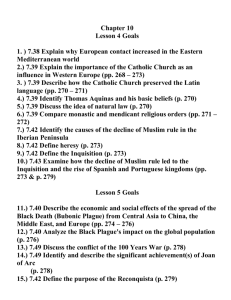

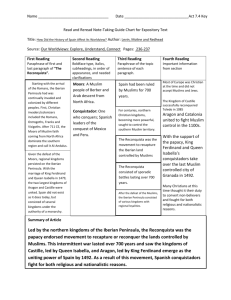

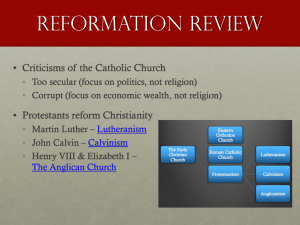

Inquisition in Spain, Portugal etc.

advertisement