The Last Lecture Topics of Discussion

advertisement

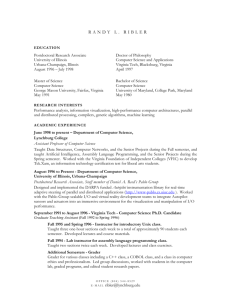

The Last Lecture Topics of Discussion: Author Randy Pausch: Randy Pausch was a professor of Computer Science, Human Computer Interaction, and Design at Carnegie Mellon University. From 1988 to 1997, he taught at the University of Virginia. He was an award-winning teacher and researcher, and worked with Adobe, Google, Electronic Arts (EA), and Walt Disney Imagineering, and pioneered the non-profit Alice project. (Alice is an innovative 3-D environment that teaches programming to young people via storytelling and interactive game-playing.) He also co-founded The Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon with Don Marinelli. (ETC is the premier professional graduate program for interactive entertainment as it is applies across a variety of fields.) Randy lost his battle with pancreatic cancer on July 25th, 2008. (Source: www.thelastlecture.com) Important People Mentioned in Pausch’s book: Jai-his wife Dylan, Logan, and Chloe- his 3 children Jeffrey Zaslow- This is who Randy Pausch would tell his story to on his daily bike rides; Zaslow adapted these stories into The Last Lecture. Michele Reiss- Jai and Randy’s psychotherapist, who specialized in treating couples in which one member is terminally ill Steve Seabolt- close friend of Randy’s Randy’s father- tough WWII veteran; founded a nonprofit group to help immigrant kids’ learn English; sold auto insurance; Randy considered him a smart man and followed his advice his whole life Randy’s mother- a former no-nonsense English teacher Tammy- Randy’s sister, who is 2 years older than him. Jack Sheriff- friend who helps paint Randy’s room when he is a child Jim Graham- Randy’s high school football coach, encouraged the fundamentals Chip Walter- co-wrote a book with William Shatner on scientific breakthroughs first mention in Star Trek; this indirectly led to Randy meeting Shatner Jon Snoddy- imaginer in charge of Disney Aladdin virtual reality ride Jessica Hodgins- co-worker of Randy he occasionally brought with him to doctor’s appointments Dr. Herb Zeh- one of Randy’s doctors Dr. Robert Woolf- Randy’s oncologist; Randy was very impressed by the way he delivered bad news Robbee Kosak- Randy’s co-worker who sees him happy in his car and sends him an email Andy van Dam- Randy is a teaching assistant to him; Andy gives him great advice by telling him, “Randy, it’s such a shame that people perceive you as being so arrogant, because it’s going to limit what you’re going to be able to accomplish in life.” (p. 68) Chris and Laura- his sister’ children Tommy Burnett- achieved his childhood dream of working on a Star Wars film Don Marinelli- a drama professor at Carnegie Mellon who co-founded the Entertainment Technology Center with Randy Dennis Kosgrove- Alice’s lead designer Caitlin Kelleher- a professor working getting girls more interested in computer programming through story telling Sandy Blatt- Randy’s former landlord who was a paraplegic Jackie Robinson- first African-American to play Major League Baseball; Randy had a photo of him in his office and Randy was surprised that few students knew his story Dennis Cosgrove- Randy fights for him to not get kicked out of school after he makes an F; eventually he takes charge of the Alice project Norman Meyrowitz- brought a lightbulb to class, which really impressed Randy Nico Habermann- an interview with this man got Randy into the PhD program at Carnegie Mellon Fred Brooks, Jr.- a highly respected computer scientist who was a lifelong mentor to Randy Jared Cohon- president of Carnegie Mellon Scott Sherman- Randy’s college roommate he goes on a scuba diving trip with Article: “A Beloved Professor Delivers the Lecture of a Lifetime” by Jeffrey Zaslow, originally published in The Wall Street Journal on September 22, 2007. Note: This was the original article that inspired people to seek out the lecture online and made Randy Pausch a worldwide phenomenon and inspiration. Randy Pausch, a Carnegie Mellon University computer-science professor, was about to give a lecture Tuesday afternoon, but before he said a word, he received a standing ovation from 400 students and colleagues. He motioned to them to sit down. "Make me earn it," he said. They had come to see him give what was billed as his "last lecture." This is a common title for talks on college campuses today. Schools such as Stanford and the University of Alabama have mounted "Last Lecture Series," in which top professors are asked to think deeply about what matters to them and to give hypothetical final talks. For the audience, the question to be mulled is this: What wisdom would we impart to the world if we knew it was our last chance? It can be an intriguing hour, watching healthy professors consider their demise and ruminate over subjects dear to them. At the University of Northern Iowa, instructor Penny O'Connor recently titled her lecture "Get Over Yourself." At Cornell, Ellis Hanson, who teaches a course titled "Desire," spoke about sex and technology. At Carnegie Mellon, however, Dr. Pausch's speech was more than just an academic exercise. The 46-year-old father of three has pancreatic cancer and expects to live for just a few months. His lecture, using images on a giant screen, turned out to be a rollicking and riveting journey through the lessons of his life. He began by showing his CT scans, revealing 10 tumors on his liver. But after that, he talked about living. If anyone expected him to be morose, he said, "I'm sorry to disappoint you." He then dropped to the floor and did one-handed pushups. Clicking through photos of himself as a boy, he talked about his childhood dreams: to win giant stuffed animals at carnivals, to walk in zero gravity, to design Disney rides, to write a World Book entry. By adulthood, he had achieved each goal. As proof, he had students carry out all the huge stuffed animals he'd won in his life, which he gave to audience members. After all, he doesn't need them anymore. He paid tribute to his techie background. "I've experienced a deathbed conversion," he said, smiling. "I just bought a Macintosh." Flashing his rejection letters on the screen, he talked about setbacks in his career, repeating: "Brick walls are there for a reason. They let us prove how badly we want things." He encouraged us to be patient with others. "Wait long enough, and people will surprise and impress you." After showing photos of his childhood bedroom, decorated with mathematical notations he'd drawn on the walls, he said: "If your kids want to paint their bedrooms, as a favor to me, let 'em do it." While displaying photos of his bosses and students over the years, he said that helping others fulfill their dreams is even more fun than achieving your own. He talked of requiring his students to create videogames without sex and violence. "You'd be surprised how many 19-year-old boys run out of ideas when you take those possibilities away," he said, but they all rose to the challenge. He also saluted his parents, who let him make his childhood bedroom his domain, even if his wall etchings hurt the home's resale value. He knew his mom was proud of him when he got his Ph.D, he said, despite how she'd introduce him: "This is my son. He's a doctor, but not the kind who helps people." He then spoke about his legacy. Considered one of the nation's foremost teachers of videogame and virtual-reality technology, he helped develop "Alice," a Carnegie Mellon software project that allows people to easily create 3-D animations. It had one million downloads in the past year, and usage is expected to soar. "Like Moses, I get to see the Promised Land, but I don't get to step foot in it," Dr. Pausch said. "That's OK. I will live on in Alice." Many people have given last speeches without realizing it. The day before he was killed, Martin Luther King Jr. spoke prophetically: "Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place." He talked of how he had seen the Promised Land, even though "I may not get there with you." Dr. Pausch's lecture, in the same way, became a call to his colleagues and students to go on without him and do great things. But he was also addressing those closer to his heart. Near the end of his talk, he had a cake brought out for his wife, whose birthday was the day before. As she cried and they embraced on stage, the audience sang "Happy Birthday," many wiping away their own tears. Dr. Pausch's speech was taped so his children, ages 5, 2 and 1, can watch it when they're older. His last words in his last lecture were simple: "This was for my kids." Then those of us in the audience rose for one last standing ovation. Article: “The Professor’s Manifesto: What It Meant to Readers” by Jeffrey Zaslow, published in The Wall Street Journal on September 27, 2007. Note: This article was published only a few days after Zaslow’s original article as Pausch’s worldwide recognition began to change his life. As a boy, Randy Pausch painted an elevator door, a submarine and mathematical formulas on his bedroom walls. His parents let him do it, encouraging his creativity. Last week, Dr. Pausch, a computer-science professor at Carnegie Mellon University, told this story in a lecture to 400 students and colleagues. "If your kids want to paint their bedrooms, as a favor to me, let 'em do it," he said. "Don't worry about resale values." As I wrote last week, his talk was a riveting and rollicking journey through the lessons of his life. It was also his last lecture, since he has pancreatic cancer and expects to live for just a few months. After he spoke, his only plans were to quietly spend whatever time he has left with his wife and three young children. He never imagined the whirlwind that would envelop him. As video clips of his speech spread across the Internet, thousands of people contacted him to say he had made a profound impact on their lives. Many were moved to tears by his words -- and moved to action. Parents everywhere vowed to let their kids do what they'd like on their bedroom walls. "I am going to go right home and let my daughter paint her wall the bright pink she has been desiring instead of the "resalable" vanilla I wanted," Carol Castle of Spring Creek, Nev., wrote to me to forward to Dr. Pausch People wanted Dr. Pausch to know that his talk had inspired them to quit pitying themselves, or to move on from divorces, or to pay more attention to their families. One woman wrote that his words had given her the strength to leave an abusive relationship. And terminally ill people wrote that they would try to live their lives as the 46-yearold Dr. Pausch is living his. "I'm dying and I'm having fun," he said in the lecture. "And I'm going to keep having fun every day, because there's no other way to play it." For Don Frankenfeld of Rapid City, S.D., watching the full lecture was "the best hour I have spent in years." Many echoed that sentiment. ABC News, which featured Dr. Pausch on "Good Morning America," named him its "Person of the Week." Other media descended on him. And hundreds of bloggers world-wide wrote essays celebrating him as their new hero. Their headlines were effusive: "Best Lecture Ever," "The Most Important Thing I've Ever Seen," "Randy Pausch, Worth Every Second." In his lecture, Dr. Pausch had said, "Brick walls are there for a reason. They let us prove how badly we want things." Scores of Web sites now feature those words. Some include photos of brick walls for emphasis. Meanwhile, rabbis and ministers shared his brick-wall metaphor in sermons this past weekend. Some compared the lecture to Lou Gehrig's "Luckiest Man Alive" speech. Celina Levin, 15, of Marlton, N.J., told Dr. Pausch that her AP English class had been analyzing the Gehrig speech, and "I have a feeling that we'll be analyzing your speech for years to come." Already, the Naperville, Ill., Central High School speech team plans to have a student deliver the Pausch speech word for word in competition. As Dr. Pausch's fans emailed links of his speech to friends, some were sheepish about it. "I am a deeply cynical person who reminds people frequently not to send me those sappy feel-good emails," wrote Mark Pfeifer, a technology project manager at a New York investment bank. "Randy Pausch's lecture moved me deeply, and I intend to forward it on." In Miami, retiree Ronald Trazenfeld emailed the lecture to friends with a note to "stop complaining about bad service and shoddy merchandise." He suggested they instead hug someone they love. Near the end of his lecture, Dr. Pausch had talked about earning his Ph.D., and how his mother would kiddingly introduce him: "This is my son. He's a doctor, but not the kind who helps people." It was a laugh line, but it led dozens of people to reassure Dr. Pausch: "You ARE the kind of doctor who helps people," wrote Cheryl Davis of Oakland, Calif. Dr. Pausch feels overwhelmed and moved that what started in a lecture hall with 400 people has now been experienced by millions. Still, he has retained his sense of humor. "There's a limit to how many times you can read how great you are and what an inspiration you are," he says, "but I'm not there yet." Carnegie Mellon has a plan to honor Dr. Pausch. As a techie with the heart of a performer, he was always a link between the arts and sciences on campus. A new computer-science building is being built, and a footbridge will connect it to the nearby arts building. The bridge will be named the Randy Pausch Memorial Footbridge. "Based on your talk, we're thinking of putting a brick wall on either end," joked the university's president, Jared Cohon, announcing the honor. He went on to say: "Randy, there will be generations of students and faculty who will not know you, but they will cross that bridge and see your name and they'll ask those of us who did know you. And we will tell them." Dr. Pausch has asked Carnegie Mellon not to copyright his last lecture, and instead to leave it in the public domain. It will remain his legacy, and his footbridge, to the world. Article: “A Final Farewell” by Jeffrey Zaslow, published in The Wall Street Journal on May 3, 2008 Note: In this article Jeffrey Zaslow reflects on what was like knowing and writing The Last Lecture with Randy Pausch. Saying goodbye. It's a part of the human experience that we encounter every day, sometimes nonchalantly, sometimes with great emotion. Then, eventually, the time comes for the final goodbye. When death is near, how do we phrase our words? How do we show our love? Randy Pausch, a professor at Pittsburgh's Carnegie Mellon University, has become famous for the way in which he chose to say goodbye to his students and colleagues. His final lecture to them, delivered last September, turned into a phenomenon, viewed by millions on the Internet. Dying of pancreatic cancer, he showed a love of life and an approach to death that people have found inspiring. For many of us, his lecture has become a reminder that our own futures are similarly -- if not as drastically -- brief. His fate is ours, sped up. Since the lecture, I've been privileged to spend a great deal of time with Randy, while co-writing his new book, "The Last Lecture." I've seen how, in some ways, he is peacefully reconciled to his fate, and in other ways, understandably, he is struggling. The lecture was directed at his "work family," a call to them to go on without him and do great things. But since the talk, Randy has been most focused on his actual family -- his wife, Jai, and their three children, ages 6, 3, and 1. For months after receiving his terminal diagnosis last August, Randy and Jai (pronounced "Jay") didn't tell the kids he was dying. They were advised to wait until Randy was more symptomatic. "I still look pretty healthy," he told me in December, "and so my kids remain unaware that in my every encounter with them I'm saying goodbye. There's this sense of urgency that I try not to let them pick up on." Through both his lecture and his life, Randy offers a realistic road map to the final farewell. His approach -pragmatic, heartfelt, sometimes quirky, often joyous -- can't help but leave you wondering: "How will I say goodbye?" Maybe 150. That's how many people Randy expected would attend his last lecture. He bet a friend $50 that he'd never fill the 400-seat auditorium. After all, it was a warm September day. He assumed people would have better things to do than listen to a dying computer-science professor in his 40s give his final lesson. Randy lost his bet. The room was packed. He was thrilled by the turnout, and determined to deliver a talk that offered all he had in him. He arrived onstage to a standing ovation, but motioned to the audience to sit down. "Make me earn it," he said. He hardly mentioned his cancer. Instead, he took everyone on a rollicking journey through the lessons of his life. He talked about the importance of childhood dreams, and the fortitude needed to overcome setbacks. ("Brick walls are there for a reason. They let us prove how badly we want things.") He encouraged his audience to be patient with others. ("Wait long enough, and people will surprise and impress you.") And, to show the crowd that he wasn't ready to climb into his deathbed, he dropped to the floor and did push-ups. His colleagues and students sat there, buoyed by his words and startled by how the rush of one man's passion could leave them feeling so introspective and emotionally spent -- all at once saddened and exhilarated. In 70 minutes onstage, he gave his audience reasons to reconsider their own ambitions, and to find new ways to look at other people's flaws and talents. He celebrated mentors and protégés with an open heart. And through a few simple gestures -- including a birthday cake for his wife -- he showed everyone the depth of his love for his family. In his smiling delivery, he was so full of life that it was almost impossible to reconcile the fact that he was near death -- that this performance was his goodbye. I'm a columnist for The Wall Street Journal, and a week before Randy gave the lecture, I got a heads-up about it from the Journal's Pittsburgh bureau chief. Because my column focuses on life transitions, she thought Randy might be fodder for a story. I was aware that professors are often asked to give "last lectures" as an academic exercise, imagining what wisdom they would impart if it was their final chance. In Randy's case, of course, his talk would not be hypothetical. I first spoke to him by phone the day before his talk, and he was so engaging that I was curious to see what he'd be like onstage. I was slightly ill at ease in our conversation; it's hard to know what to say to a dying man. But Randy found ways to lighten things up. He was driving his car, talking to me on his cellphone. I didn't want him to get in an accident, so I suggested we reconnect when he got to a land line. He laughed. "Hey, if I die in a car crash, what difference would it make?" I almost didn't go to Pittsburgh to see him. The plane fare from my home in Detroit was a hefty $850, and my editors said that if I wanted, I could just do a phone interview with him after the talk, asking him how it went. In the end, I sensed that I shouldn't miss seeing his lecture in person, and so I drove the 300 miles to Pittsburgh. Like others in the room that day, I knew I was seeing something extraordinary. I hoped I could put together a compelling story, but I had no expectations beyond that. Neither did Randy. When the lecture ended, his only plan was to quietly spend whatever time he had left with Jai and the kids. He never imagined the whirlwind that would envelop him. The lecture had been videotaped -- WSJ.com posted highlights -- and footage began spreading across thousands of Web sites. (The full talk can now be seen at thelastlecture.com.) Randy was soon receiving emails from all over the world. People wrote about how his lecture had inspired them to spend more time with loved ones, to quit pitying themselves, or even to shake off suicidal urges. Terminally ill people said the lecture had persuaded them to embrace their own goodbyes, and as Randy said, "to keep having fun every day I have left, because there's no other way to play it." In the weeks after the talk, people translated the lecture into other languages, and posted their versions online. A university in India held a screening of the video. Hundreds of students attended and told their friends how powerful it was; hundreds more demanded a second screening a week later. In the U.S., Randy reprised part of his talk on "The Oprah Winfrey Show." ABC News would later name him one of its three "Persons of the Year." Thousands of bloggers wrote essays celebrating him. Randy was overwhelmed and moved by the response. Still, he retained his sense of humor. "There's a limit to how many times you can read how great you are and what an inspiration you are," he said. "But I'm not there yet." Years ago, Jai had suggested that Randy compile his advice into a book for her and the kids. She wanted to call it “The Manual.” Now, in the wake of the lecture, otheres were also telling Randy that he had a book in him. He resisted at first. Yes, there were things he felt an urge to express. But given his prognosis, he wanted to spend his limited time with his family. Then he caught a break. Palliative chemotherapy stalled the growth of his tumors. “This will be the first book to ever list the drug Gemcitabine on the acknowlegments page,” he joked. But he still didn’t want the book to get in the way of his last months with his kids. So he came up with a plan. Because exercise was crucial to his health, he would ride his bicycle around his neighborhood for an hour each day. This was time he couldn’t be with his kids, anyway. He and I agreed that he would wear a cellphone headset on these rides, and we’d talk about everything on his mind—the lecture, his life, his dreams for his family. Every day, as soon as his bike ride came to an end, so did our conversation. “Gotta go!” he’d say, and I knew he felt an aching urge (and responsibility) to return to his family life. But the next day, he’d be back on the bike, enthusiastic about the conversation. He confided in me that since his diagnosis, he had found himself feeling saddest when he was alone, driving his car or riding his bike. So I sensed that he enjoyed my company in his ears as he pedaled. Randy had a way of framing human experiences in his own distinctive way, mixing humor here, unexpected inspiration there, and wrapping it all in an uncommon optimism. In the three months after the lecture, he went on 53 long bike rides, and the stories he told became not just his book, but also part of his process of saying goodbye. Right now, Randy's children -- Dylan, Logan and Chloe -- are too young to understand all the things he yearns to share with them. "I want the kids to know what I've always believed in," he told me, "and all the ways in which I've come to love them." Those who die at older ages, after their children have grown to adulthood, can find comfort in the fact that they've been a presence in their offspring's lives. "When I cry in the shower," Randy said, "I'm not usually thinking, 'I won't get to see the kids do this' or 'I won't get to see them do that.' I'm thinking about the kids not having a father. I'm focused more on what they're going to lose than on what I'm going to lose. Yes, a percentage of my sadness is, 'I won't, I won't, I won't.' But a bigger part of me grieves for them. I keep thinking, 'They won't, they won't, they won't.' " Early on, he had vowed to do the logistical things necessary to ease his family's path into a life without him. His minister helped him think beyond estate planning and funeral arrangements. "You have life insurance, right?" the minister asked. "Yes, it's all in place," Randy told him. "Well, you also need emotional insurance," the minister explained. The premiums for that insurance would be paid for with Randy's time, not his money. The minister suggested that Randy spend hours making videotapes of himself with the kids. Years from now, they will be able to see how easily they touched each other and laughed together. Knowing his kids' memories of him could be fuzzy, Randy has been doing things with them that he hopes they'll find unforgettable. For instance, he and Dylan, 6, went on a minivacation to swim with dolphins. "A kid swims with dolphins, he doesn't easily forget it," Randy said. "We took lots of photos." Randy took Logan, 3, to Disney World to meet his hero, Mickey Mouse. "I'd met him, so I could make the introduction." Randy also made a point of talking to people who lost parents when they were very young. They told him they found it consoling to learn about how much their mothers and fathers loved them. The more they knew, the more they could still feel that love. To that end, Randy built separate lists of his memories of each child. He also has written down his advice for them, things like: "If I could only give three words of advice, they would be, 'Tell the truth.' If I got three more words, I'd add, 'All the time.' " The advice he's leaving for Chloe includes this: "When men are romantically interested in you, it's really simple. Just ignore everything they say and only pay attention to what they do." Chloe, not yet 2 years old, may end up having no memory of her father. "But I want her to grow up knowing," Randy said, "that I was the first man ever to fall in love with her." Saying goodbye to a spouse requires more than just loving words. There are details that must be addressed. Shortly after his terminal diagnosis, Randy and his family moved from Pittsburgh to southeastern Virginia, so that after he dies, Jai and the kids will be closer to her family for support. At first, Jai didn't even want Randy returning to Pittsburgh to give his last lecture; she thought he should be home, unpacking boxes or interacting with the kids. "Call me selfish," Jai told him, "but I want all of you. Any time you'll spend working on this lecture is lost time, because it's time away from the kids and from me." Jai finally relented when Randy explained how much he yearned to give one last talk. "An injured lion still wants to roar," he told her. In the months after the talk, while chemo was still keeping his tumors from growing, Randy wouldn't use the word "lucky" to describe his situation. Still, he said, "a part of me does feel fortunate that I didn't get hit by the proverbial bus." Cancer had given him the time to have vital conversations with Jai that wouldn't be possible if his fate were a heart attack or car accident. What did they talk about? For starters, they both tried to remember that flight attendants offer terrific caregiving advice: "Put on your own oxygen mask before assisting others." "Jai is such a giver that she often forgets to take care of herself," Randy said. "When we become physically or emotionally run down, we can't help anybody else, least of all small children." Randy has reminded Jai that, once he's gone, she should give herself permission to make herself a priority. Randy and Jai also talked about the fact that she will make mistakes in the years ahead, and she shouldn't attribute them all to the fact that she'll be raising the kids herself. "Mistakes are part of the process of parenting," Randy told her. "If I were able to live, we'd be making those mistakes together." In some ways, the couple found it helpful to try to live together as if their marriage had decades to go. "We discuss, we get frustrated, we get mad, we make up," Randy said. At the same time, given Randy's prognosis, Jai has been trying to let little stuff slide. Randy can be messy, with clothes everywhere. "Obviously, I ought to be neater," Randy said. "I owe Jai many apologies. But do we really want to spend our last months together arguing that I haven't hung up my khakis? We do not. So now Jai kicks my clothes in a corner and moves on." A friend suggested to Jai that she keep a daily journal. She writes in there things that get on her nerves about Randy. He can be cocky, dismissive, a know-it-all. "Randy didn't put his plate in the dishwasher tonight," she wrote one night. "He just left it there on the table and went to his computer." She knew he was preoccupied, heading to the Internet to research medical treatments. Still, the dish bothered her. She wrote about it, felt better, and they didn't need to argue over it. There are days when Jai tells Randy things, and there's little he can say in response. She has said to him: "I can't imagine rolling over in bed and you're not there." And: "I can't picture myself taking the kids on vacation and you not being with us." Randy and Jai have gone to a therapist who specializes in counseling couples in which one spouse is terminally ill. That's been helpful. But they've still struggled. They've cried together in bed at 3 a.m., fallen back asleep, woken up at 4 a.m. and cried some more. "We've gotten through in part by focusing on the tasks at hand," Randy said. "We can't fall to pieces. We've got to get some sleep because one of us has to get up in the morning and give the kids breakfast. That person, for the record, is almost always Jai." For Randy, part of saying goodbye is trying to remain optimistic. After his diagnosis, Randy's doctor gave him advice: "It's important to behave as if you're going to be around awhile." Randy was already way ahead of him: "Doc, I just bought a new convertible and got a vasectomy. What more do you want from me?" In December, Randy went on a short scuba-diving vacation with three close friends. The men were all aware of the subtext; they were banding together to give Randy a farewell weekend. Still, they successfully avoided any emotional "I love you, man" dialogue related to Randy's cancer. Instead, they reminisced, horsed around and made fun of each other. (Actually, it was mostly the other guys making fun of Randy for the "St. Randy of Pittsburgh" reputation he had gotten since his lecture.) Nothing was off-limits. When Randy put on sunscreen, his friend Steve Seabolt said, "Afraid of skin cancer, Randy? That's like putting good money after bad." Randy loved that weekend. As he later explained it: "I am maintaining my clear-eyed sense of the inevitable. I'm living like I'm dying. But at the same time, I'm very much living like I'm still living." Since Randy's lecture began spreading on the Internet, he has heard from thousands of strangers, many offering advice on how they dealt with final goodbyes. A woman who lost her husband to pancreatic cancer said his last speech was to a small audience: her, his children, parents and siblings. He thanked them for their guidance and love, and reminisced about places they had gone together. Another woman, whose husband died of a brain tumor, suggested that Randy talk to Jai about how she'll need to reassure their kids, as they get older, that they will have a normal life. "There will be graduations, marriages, children of their own. When a parent dies at such an early age, some children think that other normal life-cycle events may not happen for them, either." Randy was moved by comments such as the one he received from a man with serious heart problems. The man wrote to tell Randy about Krishnamurti, a spiritual leader in India who died in 1986. Krishnamurti was once asked what was the most appropriate way to say goodbye to a man who was about to die. He answered: "Tell your friend that in his death, a part of you dies and goes with him. Wherever he goes, you also go. He will not be alone." In his email to Randy, this man was reassuring: "I know you are not alone." The chemotherapy keeping Randy alive took a toll on his body. By March, he was fighting off kidney and heart failure, along with debilitating fatigue. Still, he kept a commitment to go to Washington, D.C., to speak before Congress on behalf of the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network. He spoke forcefully about research needed to fight pancreatic cancer, the deadliest of all the cancers, and then held up a large photo of Jai and the kids. When he pointed to Jai, he told the congressmen: "This is my widow. That's not a grammatical construction you get to use every day.... Pancreatic cancer can be beat, but it will take more courage and funding." Randy has now stopped chemotherapy, and as he regains his strength, he hopes to begin liver-specific treatments. He is engaged in the process, but expects no miracles. He knows his road is short. Meanwhile, I feel forever changed by my time with Randy; I saw his love of life from a front-row seat. He and I traded countless emails, and I've filed them all safely in my computer. His daily emails -- smart, funny, wise -- have brightened my inbox. I dread the day I will no longer hear from him. Randy rarely got emotional in all his hours with me. He was brave, talking about death like a scientist. In fact, until we got to discussing what should be in the book's last chapter, he never choked up. The last chapter, we decided, would be about the last moments of his lecture -- how he felt, what he said. He thought hard about that, and then described for me how his emotions swelled as he took a breath and prepared to deliver his closing lines. It was tough, he said, "because the end of the talk had to be a distillation of how I felt about the end of my life." In the same way, discussing the end of the book was emotional for him. I could hear his voice cracking as we spoke. Left unsaid was the fact that this part of our journey together was ending. He no longer needed to ride his bike, wearing that headset, while I sat at my computer, tapping away, his voice in my ears. Within weeks, he had no energy to exercise. Randy is thrilled that so many people are finding his lecture beneficial, and he hopes the book also will be a meaningful legacy for him. Still, all along, he kept reminding me that he was reaching into his heart, offering his life lessons, mostly to address an audience of three. "I'm attempting to put myself in a bottle that will one day wash up on the beach for my children," he said. And so despite all his goodbyes, he has found solace in the idea that he'll remain a presence. "Kids, more than anything else, need to know their parents love them," he said. "Their parents don't have to be alive for that to happen." Chapter cut from the book: Question: Why do you think this chapter was cut? THE LOST CHAPTER The Bridge When I was first diagnosed with cancer, I went to see Carnegie Mellon’s president, Jared Cohon, to let him know. He met me in his reception area, and just making small-talk, told me I looked thin and trim. “I see you’re down to your fighting weight,” he said. “Well, that’s what I’ve come to talk to about,” I told him as he closed his door. “I’m thin because I have cancer.” He immediately vowed to do whatever he could for me, to call anyone he knew in medicine who might help. And then he took out his business card and wrote his cell-phone number on the back of it. “This is for Jai,” he said. “You tell her to call me, day or night, if there’s anything this university can do to help, or anything I can do as an individual.” President Cohon, and others at the university, did indeed make great efforts on my behalf. My surgeon later said to me: “Every time the phone rings, it’s another person politely insinuating that you’re not the guy to lose on the table.” But Carnegie Mellon also had given me a break by reconsidering my graduate-school application. Then, years later, the school hired me. Then it allowed me to set up academic programs that few other universities would even consider. Now, once again, I felt this school rallying behind me. Let me just say it: To the extent that a human being can love an institution, I love Carnegie Mellon. On the day of my last lecture, I was told that President Cohon was out of town and couldn’t attend. I was disappointed. But actually, his plan was to fly back to Pittsburgh the afternoon of the talk. He arrived halfway through the lecture, and I saw him enter the room out of the corner of my eye. I paused for a second. He stood against the side wall, watching me speak. I didn’t know it, but he was set to follow me on stage. He also had a surprise. Less than a block from the lecture hall, a new computer-science building was under construction. A 220-foot-long footbridge, three stories high, is being built to connect the computer center to the nearby arts and drama building. President Cohon had come to announce that a decision had been made to name the bridge “The Randy Pausch Memorial Footbridge.” “Based on your talk,” he ad-libbed, “we’re thinking of putting a brick wall at either end. Let’s see what our students can do with that.” His announcement was an overwhelming moment in my life. The idea of this bridge took my breath away. Turned out, President Cohon wasn’t kidding about the brick walls, either. Carnegie Mellon gave its architects and bridge designers the green light to be completely creative. They first considered having some kind of hologram of a brick wall on the bridge, allowing students to walk right through it. Now they’re planning to design the bridge in a way that gives pedestrians a sense that a brick wall is ahead of them at the end. I’ve never been a big fan of memorials or buildings being named in people’s memories. Walt Disney had said he didn’t like the idea of statues of dead guys in the park. And yet, I’m a big believer in symbols as a way to communicate. The symbolism of this bridge is just amazing to me because I've spent my career trying to be a bridge. My goal was always to connect people from different disciplines, while helping them find their way over brick walls. I am moved and pleased when I picture all the people who will one day cross that bridge: Jai, our kids, my former students and colleagues, and a lot of young people with somewhere to go. Pausch Footbridge Design To Commemorate "First Penguin Award" Note: This article describes the footbridge mentioned in the lost chapter. It is currently being built. At the Randy Pausch Memorial Service this past Monday, President Jared Cohon announced that the aluminum panel sidewalls to the Pausch Memorial Footbridge connecting the Purnell Center for the Arts to the new Gates Center for Computer Science will have an abstract design of cutout penguins. The design commemorates the "The First Penguin Award" that Pausch established for his Building Virtual Worlds class, which was given to the team of students who took the greatest risk but failed to achieve their goal. "The title of the award came from the notion that when penguins are about to jump into water that might contain predators, well, somebody's got to be the first penguin," Pausch said in his book "The Last Lecture." The design was created by Mack Scogin, architect for the new School of Computer Science Complex. In addition to the abstract design, Cohon said that the sidewalls would have programmable LED lights running continuously across the top and bottom. The LED lights are from Philips Color Kinetics, founded by Carnegie Mellon alumni George Mueller and Ihor Lys, who was recently named National Inventor of the Year by the Intellectual Property Owners Education Foundation. C & C Lighting Design, owned by Drama Professor Cindy Limauro and her husband, Christopher Popowich, are creating the lighting design. "We will be programming the lights to change colors in a variety of visual looks that can also be triggered by motion sensors. In addition to our lighting, students will be able to log on to the system at designated times to create their own lighting looks," Limauro said. Near the Gates Center, the bridge also will have a brick wall covered with more aluminum penguin cutout panels and LED lights. The barrier serves as a reminder of Pausch's adage that brick walls exist to make you realize how badly you want something. "It is only when you get to the end of the bridge that you realize it isn't a dead end brick wall. There is a door to the right that goes into the building," Limauro said. (Source: http://www.cmu.edu/news/weekly/2008/September/september-25.shtml) Information from Carnegie Mellon University: We at Carnegie Mellon have been blessed to know and work with Randy Pausch and to see the profound influence he has had on our students, on entertainment technologies and on the teaching of computer science. We--all of us-are fortunate that Randy has been able to record his insights into how a good life is lived. Randy’s gifts of inspiration are no longer restricted to our lecture halls and labs; they are now here for all to read and experience. — Jared L. Cohon, President, Carnegie Mellon University Carnegie Mellon is a private research university with more than 10,000 undergraduate and graduate students participating in a distinctive mix of programs in engineering, computer science, robotics, business, public policy, fine arts and the humanities. A global university, Carnegie Mellon has campuses in Pittsburgh, PA, Silicon Valley, CA, and Doha, Qatar. Carnegie Mellon also has degree-granting programs in Asia, Australia and Europe. Watch videos and get more information about The Last Lecture DVD, Randy's other lectures, and media coverage for the book at Randy Pausch's Carnegie Mellon website. The Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University is the premiere professional graduate program for interactive entertainment as it is applied across a variety of fields. Co-founded by Don Marinelli and Randy Pausch, the ETC emphasizes leadership, innovation and communication by creating challenging experiences through which students learn how to collaborate, experiment, and iterate solutions. Graduates are prepared for any environment where technologists and artists work closely on a team; like theme parks, children and science museums, web sites, mobile computing, video games and more. (Source: www.thelastlecture.com) www.alice.org Note: Alice is the program that Randy Pausch initiated at Carnegie Mellon. It is available to download for free at www.alice.org. It looks pretty awesome, so if you are interested in creating animation and video games, check it out. Alice is an innovative 3D programming environment that makes it easy to create an animation for telling a story, playing an interactive game, or a video to share on the web. Alice is a freely available teaching tool designed to be a student's first exposure to object-oriented programming. It allows students to learn fundamental programming concepts in the context of creating animated movies and simple video games. In Alice, 3-D objects (e.g., people, animals, and vehicles) populate a virtual world and students create a program to animate the objects. In Alice's interactive interface, students drag and drop graphic tiles to create a program, where the instructions correspond to standard statements in a production oriented programming language, such as Java, C++, and C#. Alice allows students to immediately see how their animation programs run, enabling them to easily understand the relationship between the programming statements and the behavior of objects in their animation. By manipulating the objects in their virtual world, students gain experience with all the programming constructs typically taught in an introductory programming course. (Source: www.alice.org) Article: “Shrines to Childhood” by Kate Stone Lombardi, published in The New York Times on April 5, 2009 Note: This article talks about what happens to childhood bedrooms after the child moves out. It is worth noting since many of you will be going away to college next year, and Randy Pausch had such an attachment to his childhood room. MY son’s room has been described more than once as a shrine. The object of his homage? The New York Rangers. We are not just talking about a few posters on the wall. Nearly every square inch trumpets Paul’s support of the team. A huge Rangers banner that hangs from the ceiling dominates the room. In the corner is a larger-than-life cardboard cutout of Wayne Gretzky, hockey stick outstretched, waiting for a pass. The bed has not only a Rangers cover and a Rangers pillow, but also sheets with hockey pucks on them. There are signed hockey sticks over the windows, which themselves are decorated with Rangers decals. The computer mouse pad has the team logo. There are framed, signed Rangers jerseys above the computer. It goes without saying that the walls are covered with posters, photographs and calendars that celebrate the team. (Ticket stubs from games are kept in a separate box, memories too precious to stick on the wall.) I think you get the picture. My son is the kind of fan whose spirits rise and fall with the performance of the team, who follows every blip of Rangers news, remains highly opinionated about the strengths and weaknesses of each player, and who sounds to me at this point as if he’s ready to step up to the coach’s job, in the event that the latest one doesn’t work out. This room didn’t come together overnight, of course. The memorabilia was collected from the time he was an early fan — back in his elementary school days — until now. Today he is a college sophomore. He still lives and breathes hockey. But he doesn’t really live in that room anymore. I am careful about going in there while he’s at school, because it makes me miss him too much. Just standing in the doorway sets me back. That’s because to me this room is more than a monument to a hockey team. It’s really a shrine to the little boy who grew up there. Paul was placed in a crib as a newborn in that room. He spent endless hours of his childhood in there, playing with his Matchbox cars, painstakingly organizing his hockey cards, reading and, as he got older, studying, cramming for SATs, logging hours on Facebook with his friends and, finally, packing for college. When I look past all the Rangers stuff, I can still see remnants of other parts of Paul’s childhood. High up on a shelf is the stuffed penguin he once slept with. There are a few little cars on the shelf — and of course, a few miniZambonis. There are class pictures from elementary school, team pictures from high school, soccer trophies and a program from a jazz concert he played in. Recently, I spotted a brochure about a college study-abroad program — he hopes to spend a semester in Spain next year. There was also a pile of clothes he had outgrown. As it is, he can barely fit his long frame in that childhood bed. This, I know, is a room in transition. His sister’s room is just down the hall, and farther along in the process of transforming from a child’s room to the room of someone who once lived there. Jeanie graduated from college two years ago. Her room, too, mirrors the girl she once was. The canopied bed still has a Laura Ashley spread, and there are matching curtains on the windows. But there is also a Zebra-patterned throw that appealed to her in middle school. At one point she balked at her pink walls and carpets — now the carpet is a moss green and the walls a sky blue. It feels as if you are outside and it also feels very much like a reflection of Jeanie’s spirit. Photos of laughing groups of friends are tacked on the wall, spread on the bureau and tucked into the corners of her mirror. There are half-melted candles and countless hair accessories. The shelves and the desk are crammed with dozens of books, ranging from childhood favorites to Michel Foucault’s “Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth,” with plenty of trashy novels and great literature in between. But things are also starting to disappear from that room. A lamp went to her apartment in the city. So did some sheets and blankets. And a small painting that used to hang on her wall. And some framed photos. It’s still my daughter’s room, but as she settles more deeply into her independent life, her essence gets more and more stripped out of those four walls. I would be lying to say that I miss the disorder — the scattered papers, the piles of clothes, the dirty tea mugs — that were also very much a part of Jeanie’s occupancy. But I do miss the girl who lived there. On a recent college vacation, Paul brought a friend home, and as they entered his room, it seemed like the Rangers shrine had for the first time become slightly embarrassing. “It’s sort of a little boy’s room,” he said with a small smile. Paul will probably always root for the team and follow its fortunes. In the years to come, he will see great players rise and fall, playoffs come and go, and coaches hired and fired. And if all the stars align, he will see the Rangers bring home another Stanley Cup, something that will bring him enormous joy no matter what age he’ll be. But the little-boy adoration that was reflected in his room has already been replaced with a more nuanced understanding of professional sports. I suspect, over time, his monument to the hockey team will slowly be dismantled. A poster here. A signed photograph there. I doubt that the Rangers bedspread will make the move to an adult apartment, though you never know. If it doesn’t, I doubt I will ever remove it. The Last Lecture Homework Assignment: "If you lead your life the right way, the karma will take care of itself. The dreams will come to you."- Randy Pausch Make a list of your childhood and/or current dreams (probably you will have at least five, but I am not requiring that you have a certain number of dreams—this is about your dreams, after all). They must fit onto a standard piece of printer paper, and you must also include a photograph of yourself as a child. You may also choose to creatively decorate this to fit your personality. Be forewarned that this project will be hung up in the classroom. It should be formatted as thus: YOUR NAME’S DREAMS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. PHOTOGRAPH This project will be worth 25 points. The Last Lecture Cooperative Group Activity One of the many wonderful points Randy Pausch made in his book was the need for his students to work together and contribute equally. With that in mind, I am going to assign you to a group of approximately four and give you a box of paper clips. Your goal will be to put together the biggest, best, most creative object you can with these paper clips. When the time expires, everyone reconvenes at a predefined location for the show-and-tell and judging process. This in-class activity will be worth 10 points. Short Essay #1: Illustrative/Exemplification essay on The Last Lecture For your first essay, you are going to write your own 500-750 word essay giving advice on how to live your life, based on the life lessons you have learned so far. You need to break up your advice into five to seven short chapters and give each chapter a title (and you will need to give the overall essay a title). You will also need to include short anecdotes from your life to support your life lessons. You will turn in this typed essay on __________________. It will also need to be turned in to www.turnitin.com by the time class begins. You will put the hard copy draft on top, with your www.turnitin.com receipt stapled underneath. Be prepared to share one of your chapters with the class the day it is due. This essay is worth 75 points.