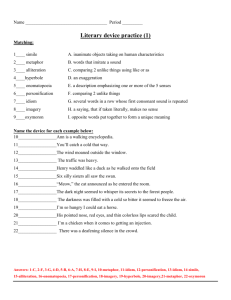

The Onlooker

advertisement