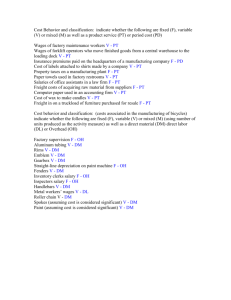

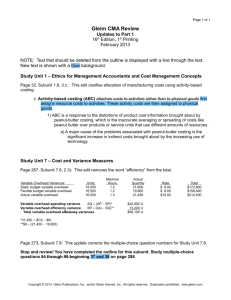

ACC 311 - Managerial Accounting

advertisement