UNIT I - Kentucky Interagency Council on Homelessness (KICH)

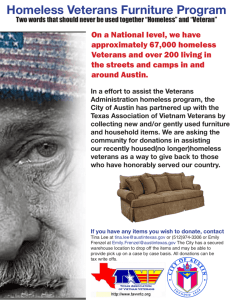

advertisement