criminal - kurtz

advertisement

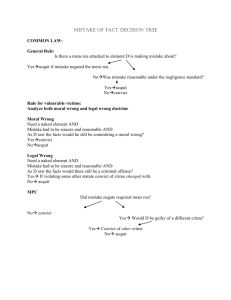

Criminal Fall 2003 Outline Anisa Abdullahi Background I. Sources of criminal law a. Statutes: Legislature defines what is against the law b. Constitution: Defines what is permissible in law c. Administrative Agencies: Create regulations for particular industries d. Courts: Create common-law rules II. Basic elements of every crime a. A voluntary act (actus reus) b. Culpable intent (mens rea) c. Concurrence between the mens rea and the actus reus d. Causation of harm III. Model Penal Code a. Adopted in 1962 by the American Law Institute—judges, lawyers, legal scholars, etc. i. To clarify and improve the law ii. A rational way of looking at the law iii. Restatement was too broad b. It is the law nowhere c. MPC says there are three types of elements to a crime: i. Conduct—all crimes ii. Circumstance—some crimes iii. Results—some crimes d. Divided into two parts: i. First part has general provisions with definitions, mens rea, defenses, etc. ii. Second part details the criminal codes dealing with actual crimes like theft, rape, arson, etc. IV. Theories of punishment a. Utilitarianism: Punishment is justifiable because it promotes the interest of society; it achieves some other good—maintaining social order by preventing crime (possible problem: assumes people will/can be deterred or rehabilitated); forward-looking i. Deterrence (General): To maintain social order 1. Concentrates on preventing future crimes by warning society not to do it 2. Punishment designed to minimize or eliminate anti-social behavior 3. Provides an indirect warning of consequences through the example criminal if they too choose to violate the law ii. Rehabilitation (Specific deterrence): To reform the person who committed the crime 1. Concentrates on preventing future crimes by reforming or “fixing” the criminal 2. Trying to entice the offender away from a life of crime iii. Incapacitation: To keep those who don’t follow the law out of society 1. Idea is that you can’t commit a crime if you are locked up—specific prevention 2. Protects the innocent from those who have proven themselves to be dangerous b. Retribution: Punishment is justified on the grounds that wrongdoing merits punishment; doesn’t depend on the result (unlike the way utilitarian theories are forward-looking) i. The offender deserved the punishment because of wrong behavior (legally, not necessarily morally) ii. Idea of an eye for an eye 1. Makes the victim or victim’s family feel better iii. Not designed to have an impact on anyone else but the criminal iv. Many will say that this is how criminal punishment began—historical rather than modern (but people see it as a good theory) V. Levels of punishment a. Necessary to punish in proportion to the seriousness of the crime: i. If the punishment is the same for all crimes, people will be more likely to commit the more serious ones ii. If the punishment is too severe, the jury will be eager to acquit for small crimes VI. b. Retribution is not only a rationale for punishment, but also a limit on punishment Burden of proof a. Burden of production—to first bring in particular evidence i. D has burden of production for an affirmative defense like insanity or self-defense 1. This then shifts to ultimate burden of persuasion back to the state ii. State has burden of production for mens rea b. Burden of persuasion—ultimate task of convincing the finder of fact (usu. jury) i. The state has the burden of proving that D acted culpably with regard to all material elements of the crime (beyond a reasonable doubt) ii. If it’s a tie, D wins e. Lenity principle i. Interpreting statutes such a way so that if there is ambiguity in the statute, favor goes to D. ii. Reasons for this principle: 1. Want to avoid wrongful convictions a. Better 10 go free than 1 innocent go to jail 2. Puts the burden of proof on the state as it should be a. State has to prove beyond a reasonable doubt b. D only has to provide a reasonable doubt 3. Once D is acquitted, no double jeopardy a. Prevents state from appealing an acquittal Actus Reus I. Two Levels a. General: Every crime must have an act b. Specific: The specific act required for a particular crime II. Why have an actus reus requirement? a. Evidentiary function: i. Bad act is the best way to tell what the bad thoughts were—objective manifestation of bad intent ii. Since D isn’t required to testify, bad act might be the best way to get information b. Act makes the actor more dangerous than just having thoughts i. We don’t want to punish people for things they think but don’t actually do ii. Provides a place to repent/turn back (before acting): locus poenitentiae c. People need to know what bad acts are in order for deterrence to work d. Promotes the idea of culpability by holding people responsible for their acts e. Proctor: D had not crossed the line to committing an overt act when he simply “kept” a place with the intent to sell liquor. (If he had actually possessed liquor it might have been different) III. 6 Elements of Actus Reus a. Past—has already occurred b. Voluntary—D chose to do it c. Bad/Wrongful/Dangerous d. Conduct—not just thoughts e. Specified in advance f. By statute IV. Omission a. Usually an actus reus is an affirmative kind of behavior b. Generally the law does not punish the failure to do something i. Misfeason—doing something wrong ii. Nonfeason—not doing something c. Some states do have laws that make people act, but for the most part we don’t want to make people do things they don’t want to do i. Autonomy argument: 1. People have the right to live their lives as they choose, with the right to walk away as well as the right to be a hero V. 2. Obligating people to do something leaves them without the option to act out of the goodness of their hearts ii. Morality argument: 1. State doesn’t have the right to define morality 2. There is a difference between doing something bad and not doing something good iii. Mechanical argument: 1. Difficult to determine who would be responsible 2. Hypo: Burning building with child inside while people were walking by d. Exception to the general rule: People who have a legal duty i. Everyone has to pay income taxes ii. Jones: When a woman didn’t feed the baby she was talking care of for her friend, the court reversed for a new trial because jury was not instructed to find a legal duty before convicting for involuntary manslaughter. iii. Examples of when there might be a legal duty (from Wisconsin): 1. Statute imposes it 2. Status relationship—parent and child 3. Contractual duty 4. Voluntarily assumed care (sequester)—telling everyone you’re going to do it iv. Seems we can punish omissions Voluntariness a. Courts generally read this requirement into statutes as it is rarely explicitly stated, but the MPC does explicitly state that it is required b. Lack of voluntariness negates the actus reus element i. Newton: D was carrying a gun and ammunition on a plane traveling from Luxembourg to the Bahamas which had to land in NY. Court ruled that he did not voluntarily violate the NY statute that made carrying the weapon and ammunition illegal. c. MPC § 2.01: Requirement of Voluntary Act i. (1) A person is not guilty of an offense unless his liability is based on conduct which includes a voluntary act… ii. (2) The following are not voluntary acts within the meaning of this Section: 1. (a) a reflex or convulsion 2. (b) a bodily movement during unconsciousness or sleep 3. (c) conduct during hypnosis or resulting from hypnotic suggestion 4. (d) a bodily movement that otherwise is not a product of the effort or determination of the actor, either conscious or habitual iii. …(4) Possession is an act, within the meaning of this Section, if the possessor knowingly procured or received the thing possessed or was aware of his control thereof for a sufficient period to have been able to terminate his possession. d. Insanity v. Automatism i. Insanity is rarely used as a defense 1. Usually not very successful 2. Burden of proof on D 3. Go to the asylum if proven ii. Automatism negates the actus reus 1. D raises a reasonable doubt with outside evidence (still hard to prove) 2. A version of involuntariness 3. Burden of proof on the state to override doubt 4. Go home if proven 5. (Huey) Newton: D shot officer after being shot in the abdomen. Court let the jury consider that D acted out of “reflex shock.” e. Lack of Voluntariness Defense i. Not very broad in scope ii. Same thing as saying “I didn’t do it.” iii. Some acts are such that the philosopher would say they were involuntary, but the law will say they are voluntary 1. For example: Man stealing bread in order to feed his starving kids a. Involuntariness requires no choice, this is just a bad choice between stealing and letting kids starve 2. However, man with a gun to his head is acting under duress and has a defense—but this is not an involuntariness defense 3. Decina: D had epileptic seizure while driving and killed four people on sidewalk. Court ruled that he was criminally liable because he knew he was subject to attacks and deliberately made the choice to drive. 4. Martin: D was on highway manifesting an intoxicated condition. Court ruled that he was involuntarily and forcibly carried there by the police and reversed the conviction. 5. Johnson: D took cocaine while pregnant and was convicted for delivering drugs to her baby just after it was born and before the umbilical cord was cut. Court reversed because there was inadequate evidence of delivery, even if there was an act there was no proof it was voluntary, and even if it was voluntary the legislature had said it didn’t want to punish mothers for delivering crack babies. (illustrates the principle of lenity) f. Time Framing: Sometimes our judgment about what is going on is affected by exactly how broad or narrow a picture we take of the episode. i. If we take a short/narrow picture: Instant behavior looks more involuntary ii. If we take a long/broad picture: Long-term behavior looks more voluntary 1. Example: In Decina case, the seizure looks involuntary but when you look back to see that he chose to drive knowing he had a condition. g. Involuntariness vs. Lack of Mens Rea i. Involuntariness says, “I didn’t choose to act.” ii. Lack of mens rea says, “I chose to act, but I didn’t mean to…” 1. As a practical matter, it isn’t really going to be any different in terms of what happens to D who comes out not guilty if it was involuntary or if there is a lack of mens rea iii. Closely tied to a lack of mens rea defense in that in these cases D could have recast his argument to say that he didn’t intend to do it. However, arguing a lack of mens rea necessarily means you concede the actus reus. h. Status Crimes i. Generally, a person cannot be punished for mere “status.” 1. Narrow interpretation: Status is not an act 2. Broader interpretation: Status is not a voluntary act ii. Robinson: D was convicted for being addicted to narcotics and argued that it was unconstitutional to do so. Court ruled that an addiction was more like having an illness and not an actual act, reversing the conviction. (Dissent argued the slippery slope—next case will be the addicted user, then the addicted user who had to steal, etc.) 1. Broad interpretation—the Constitution requires voluntariness and you can’t be convicted for something you have no control over 2. Narrow interpretation—the Constitution doesn’t necessary require a voluntary act, but it requires an act 3. Note two rationales for the decision: a. Involuntary conduct cannot be punished. D could not stop being an addict without medical assistant. b. Punishment must be for past, not future, conduct. D’s addiction implied a desire or propensity to commit punishable acts in the future. iii. Powell: D convicted for being intoxicated in a public place. Court upheld the conviction because he wasn’t charged with an alcoholic (status) but rather for being in a public place while drunk (act). 1. In line with the narrow view of Robinson because it required an act. 2. But also looks like the broad view in that it must be saying D acted voluntarily or it would be reversing the trial court’s finding that he had a compulsion to appear in public. Mens Rea I. Levels of culpability a. Virtually every crime requires some mental element or culpability with regard to the actus reus be proved beyond a reasonable doubt (exception: strict liability crimes) b. Common law uses many different terms for defining mens rea (very messy) i. Mens rea ii. Culpability iii. Criminal intent—misleading because it suggests we only punish people when the intend; we sometimes punish people who can honestly say they didn’t intend to do the crime c. MPC §2.02(2): Kinds of Culpability Defined (edited—full on page 1170) i. Purposely- A person acts purposely with respect to an element of an offense when it is his conscious object to engage in conduct of that nature or to cause such a result or he is aware of, believes, or hopes such circumstances exist. ii. Knowingly- A person acts knowingly with respect to an element of an offense when he is aware that his conduct is of that nature or that such circumstances exist and he is aware that it is practically certain that his conduct will cause such a result. iii. Recklessly- A person acts recklessly with respect to an element of an offense when he consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the element exists or will result from his conduct. The risk must be such that its disregard involves a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a law-abiding person would observe in the actor’s situation. iv. Negligently- A person acts negligently with respect to an element of an offense when he should be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the element exists or will result from his conduct. The risk must be such that his failure to perceive it involves a gross deviation from the standard of care a reasonable person would observe in the actor’s situation. d. For virtually all crimes, knowing behavior is punished to the same degree as purposeful behavior. e. Chart on page 217 regarding four levels of culpability (three types of elements: conduct, circumstances, or result) i. Purposely 1. Circumstance: He is aware of such circumstances or hopes they exist 2. Result: It is his conscious object to cause such result 3. Conduct: It is his conscious object to engage in conduct of that nature ii. Knowingly 1. Circumstance: He is aware that such circumstances exist 2. Result: He is aware that it is practically certain that his conduct will cause such a result 3. Conduct: He is aware that this conduct is of that nature. iii. Recklessly 1. Circumstance: He consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element exists 2. Result: He consciously disregards a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element will result from his conduct. (gross deviation from the standard conduct of law-abiding persons in this situation) iv. Negligently 1. Circumstance: He should be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element exists. 2. Result: He should be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element will result from his conduct. f. Default level of culpability—Recklessly (at least) i. Thus if a legislature wants negligence to be the mens rea, it must expressly state so. (think objective vs. subjective culpability) ii. MPC § 2.02(3) “When the culpability sufficient to establish a material element of an offense is not prescribed by law, such element is established if a person acts purposely, knowingly or recklessly with respect thereto.” II. III. IV. V. g. MPC § 2.02(4): Stated culpability applies to all material elements of the crime unless otherwise provided. h. MPC § 2.02(5): If a certain level of culpability is required, any higher level of culpability will suffice. (If recklessness is required, then purpose or knowledge works just as well) i. MPC § 2.02(7): If you know to a substantial certainty that something is true, the fact that you don’t know for sure (avoid finding out—willful blindness) that it’s true is not a defense. j. MPC § 2.02(8): Requirement of willfulness is satisfied by acting knowingly. k. Subjective v. Objective Culpability i. It might be more accurate to show that there is a jump between the first three levels and negligence. Some argue negligence should not even be criminal. ii. There is a difference between punishing someone subjectively because of what evilness was in his mind—purpose, knowing, reckless—and objectively because of what a reasonable person would have had in his mind—negligence. iii. The negligent person was unaware of the risk and is not evil in the same way as the other three levels. Why have a mens rea requirement? a. Punishment wouldn’t seem fair if the person didn’t mean to do it b. If you punish people without requiring fault, it wouldn’t really deter people from doing bad things since they can be punished for acting “innocently” c. Faulkner: D was trying to steal rum and light a match which burned down the ship. Court ruled that there had to be some mental element attached to the setting of the fire beyond that for stealing rum. Normative v. Descriptive a. Normative (value-laden/emotional): i. English student would say that it means “evil” b. Descriptive (objective) i. Statute would say it means “intentional” General v. Specific Intent a. General: Intending to do an act that leads to the consequences; refers to the broader question of D’s blameworthiness or guilt b. Specific: Intending the resulting consequences; refers to the mens rea requirement of any crime Exception: Strict Liability a. Three ways to define strict liability i. Pure strict liability: No culpability (mens rea) is required for any element of the crime ii. Impure (partial) strict liability: Mixture between culpability and no culpability requirements for different elements of the crime iii. Substantive strict liability: Prosecution and conviction where there is no moral culpability 1. Example: Driving over the speed limit—only reason we think it is a bad thing is because it is against the law a. Mala in se—wrong in itself b. Mala prohibitum—wrong because of statutes b. Under strict liability, acting reasonably (off the chart) is no defense. Perfection is required in order to avoid conviction. c. Arguments for strict liability i. Retribution: D did something wrong and should be punished ii. Burden of proof: Hard to prove the mental state of D iii. To protect the rights of the people being injured. iv. Deterrence: 1. Specific: D will act more carefully next time. 2. General: Others will act more carefully based on example set by punishing D v. Incapacitation: Even if D had no mental culpability, at least he won’t do it while in jail. vi. Forces people to check out what the laws are, otherwise they might remain ignorant on purpose d. Arguments against strict liability i. Deterrence won’t work because people will know that they can be punished even if they act carefully or “innocently” VI. ii. Punishment without blameworthiness seems immoral and wrong iii. If you look really closely at the situation, there probably was something D did wrong anyway. e. MPC’s take on strict liability i. MPC § 2.05(2)(a): “When absolute liability is imposed with respect to any material element of an offense defined by a statute other than the Code and a conviction is based upon such liability, the offense constitutes a violation..” ii. MPC § 1.04(5) says a violation is punishable only by a fine or other civil penalty. iii. MPC (and some states) has a big problem with strict liability f. Complicity: MPC § 2.06(1) Liability for Conduct of Another i. “A person is guilty of an offense if it is committed by his own conduct or by the conduct of another person for which he is legally accountable, or both.” g. Note that the MPC says a strict liability offense is not a crime, but a violation i. MPC is reluctant to accept strict liability because punishment without blameworthiness seems immoral and wrong h. Balint: D convicted for selling opium derivative without proper documentation even though he did not know them to be as such. Court ruled that if there was a greater good, punishing people without “scienter” (knowledge) is allowed. i. Kurtz argues this is backwards because the mala in se crimes require culpability while regulatory offenses are strict liability—more dangerous crime is harder to prove. ii. The court’s argument was that the regulatory violations could affect many people—public welfare offenses i. Dotterweich: D charged with vicarious liability for his company’s mislabeling of drugs and court upheld conviction. i. Kurtz calls this strict liability on strict liability because both the worker and D were strictly liable. j. Morrisette: D took air force bomb casings from bombing range and sold them for profit, thinking they belonged to no one. Court ruled that this was not the type of crime that merited strict liability— “knowingly converts government property” and that he had to know it was government property in order to be convicted. k. X-Citement Video: Supreme Court upheld sexual exploitation of minors act but said that culpability was required with regard to the minor’s age—D must have scienter of child’s youth. l. U.S.D.C.: D produced a depiction of sexual performance of a minor and statute did not contain the word “knowingly” because legislature had removed it. Court ruled D would have a defense if he could present evidence of mistake with regard to her age. Mistake of Fact a. Generally, a mistake of fact is a defense if it negatives the mens rea requirement for any material element of the offense—MPC 2.04(1) b. Ignorance differs from mistake (i.e. not knowing something vs. knowing something wrong), but it can also serve as a defense if it negatives the mens rea requirement c. To determine if mistake or ignorance negatives the mens rea requirement, the court must look at: i. The wording of the applicable statute, noting two rules of construction: 1. It is assumed that the offense is not strict-liability offense unless the statute says otherwise 2. If the statute requires a particular level of culpability with regard to one material element of the offense, it is assumed that the level of culpability is required for each material element of the offense (distributive culpability rule) ii. If the statute is silent w/ regard to culpability, assume that the statute requires the default level of culpability (recklessness under MPC) d. Ryan: D was convicted of attempting possession of a hallucinogen weighing more than 625 mg, even though he argued he did not know how much there was. Court reversed because the statute didn’t have a specific reference to culpability for knowing the weight and thus it would have to construe in D’s favor. (notions of lenity, anti-strict liability) e. Even an unreasonable mistake about a material element of a crime can negative the culpability required in regard to an element of the crime (i.e. the age of a minor in statutory rape case)—IS THIS RIGHT???? VII. i. MPC § 2.04(1)(a): “Ignorance or mistake as a matter of fact or law is a defense if (a) the ignorance or mistake negatives the purpose, knowledge, belief, recklessness or negligence required to establish a material element of the offense.” ii. But the more unreasonable the mistake is, the more likely the jury is going to find D acted recklessly, rather than mistakenly. 1. If the mistake is particularly unreasonable, the jury might even find D acted knowingly iii. What is a reasonable mistake? 1. Reasonable to mistake age when girl shows you an ID, looks the age, friend tells you she’s that age 2. Unreasonable to mistake age when you think she’s 16 and you’re picking her up at middle school f. Lesser moral/legal wrong i. Opposed to the notion of mens rea is the notion that if you’ve done something wrong the fact that it turns out that you’ve done something even worse than that means that because you’ve done the wrong you should be punishable for the worse thing and not the lesser wrong you thought you were doing. 1. Kurtz took a hat he thought was worth $6 (petty theft), but it turns out to be a rare hat worth 5 billion dollars (grand theft)—if you subscribe to the lesser legal wrong doctrine, you would say that he knew he was doing something wrong and can be convicted for grand theft. a. He had the mens rea for petty theft b. It’s his problem that he ended up committing grand theft c. Normally the state would have to prove a mens rea for the greater crime 2. Everybody knows you shouldn’t take young girls from their family, Kurtz thought she was 17 (which if she had been would not have been a illegal), but she turns out to be 13 (which is illegal)—the lesser moral wrong doctrine would say there is no problem with conviction for the crime because he knew he was committing the moral wrong 3. These are ways to convict of a crime without proving the requisite mens rea. ii. Prince: D took a girl under 16 years of age away from her home, but she was actually 14. Judge Blackburn said his mistake about her age was not a defense because there is no mens rea requirement with regard to her age. Judge Brett says that if he is non-culpable with regard to her age, he is not guilty—lesser legal wrong. Judges Bramwell and Denman say the act is immoral in itself to take a girl from her family and thus he is guilty—lesser moral wrong. Conviction was upheld. g. Lima: Court decided to follow MPC and say that the default requirement for mens rea was recklessness. Shows that 2.02 is the most influential provision in the MPC. h. Guest: D were charged with statutory rape of a 15 year old, but argued they thought she was 18. Court allowed a defense of reasonable mistake with regard to her age. i. There is such a thing as a reckless mistake Mistake of Law a. Traditionally, mistake of fact is a defense but mistake of law is not. i. “Ignorance of the law is no excuse”—Everyone is presumed to know the law 1. Encourage people to know the law 2. Don’t want to encourage people to remain ignorant 3. Don’t want unequal treatment for the mistaken and the nonmistaken 4. Baker: D argued he did not know it was against the law to peddle counterfeit Rolex watches. Court knowledge of the illegality of the behavior is not required and thus lack of knowledge is not a defense. ii. Argument for why it should be a defense: 1. It is unfair because it presumes everyone knows the law not only of the place they live, but of other places as well 2. If no knowledge then no deterrence 3. If no knowledge no mens rea or culpability iii. Argument for why it should not be a defense: b. c. d. e. 1. Makes law too subjective because it puts a premium on ignorance 2. If it were it would put a great burden on the state by requiring proof that D knew the law a. The state is required to prove nothing regarding D’s knowledge of whether or not his behavior is proscribed by law unless the definition of the offense so provides—MPC 2.02(9) Line between mistake of law and mistake of fact is permeable i. One can often transform one into another (like the above examples) 1. I thought he was already dead—sounds like fact 2. But to the extent that we define homicide as killing a person—it could be a mistake of law Exception to the general rule is when the mistake negatives the mens rea—MPC doesn’t distinguish between mistake of fact and mistake of law: i. MPC § 2.04(2): “Although ignorance or mistake would otherwise afford a defense to the offense charged, the defense is not available if the defendant would be guilty of another offense had the situation been as he supposed. In such case, however, the ignorance or mistake of the defendant shall reduce the grade and degree of the offense of which he may be convicted to those of the offense of which he would be guilty had the situation been as he thought it was.” Governing vs. Nongoverning i. Governing law: Mistake as to how the offense is defined (about the law you are being prosecuted under)—not a defense ii. Non-governing law: Mistake of law embedded in the meaning of a particular circumstance element—can be a defense iii. The problem with this formulation is that the non-governing law is incorporated into the governing law and thus the distinction is unclear. iv. Bray: D did not know he was a felon (non-governing law) or that he had to register as such in the state of California after moving there (governing law). Court allowed the defense of mistake because it was about non-governing law—Either his mistake negated the mens rea or he had an excuse for his lack of knowledge. v. Smith: D unlawfully removed fixtures (governing law) he had installed in apartment, damaging the walls, floors, etc., arguing he thought it was his property (non-governing law). Court allowed the defense of mistake because it was about non-governing law. Mistake of law as an excuse i. Some excuse defenses include: 1. Insanity—you have the mens rea, you just don’t know it’s wrong. 2. Duress or coercion ii. Acting in reliance upon statement of the law 1. MPC 2.04(3): “A belief that conduct does not legally constitute an offense is a defense to a prosecution for that offense based upon such conduct when: a. (a) the statute or other enactment defining the offense is not known to the actor and has not been published or otherwise reasonably made available prior to the conduct alleged, or b. he acts in reasonable reliance upon an official statement of the law, afterward determined to be invalid or erroneous, contained in (i) a statute or other enactments; (ii) a judicial decision, opinion or judgment; (iii) an administrative order or grant of permission; or (iv) an official interpretation of the public officer or body charged by law with responsibility for the interpretation, administration or enforcement of the law defining the offense.” 2. Hopkins: Reverend erected sign soliciting his ability to perform marriages despite knowing there was a statute against it because the state’s attorney had advised him sign would not violate law. Court upheld conviction because D didn’t contend the DA had mislead him, only that he didn’t know he was violating the law. a. Probably not reasonable to rely on DA either, since he knew the law. VIII. iii. Unique statute 1. Lambert: Where felons had to register and D omitted to do so, the court said D had the burden of proving he didn’t have notice of the statute (affirmative defense). a. Courts generally have not followed this decision. iv. If D made a bona fide effort to determine applicability of law 1. Long: Where D’s lawyer told him his divorce was legitimate so he got remarried and violated a bigamy law, the court ruled he had the option of a defense. a. Three types of arguments D can make: i. Didn’t know it was against the law—not a defense ii. Didn’t know the law applied—not a defense iii. Didn’t know the law applied and tried in good faith to find out if it did—gets a defense 2. Twitchell: Where Christian Scientists read church handbook and relied on Attorney Generals’ interpretation of the law, the court reversed and left it open for prosecution to take to retrial. Mistake continued a. “Willful” i. Some courts do necessarily see this word to mean that ignorance is a defense. ii. Some courts say that it means D had to know about the existence of the rules in order to be held in violation. b. Defense of mistake of fact or law can be seen two ways i. Negation of mens rea 1. Prohibits prosecution from making a prima facie case 2. Burden of proof remains on the state ii. Affirmative defense 1. An excuse that D’s behavior is not blameworthy 2. Burden of proof shifts to D Homicide I. Generally a. The actus reus of all homicides is the unlawful taking of another human life b. Different kinds of homicides are distinguished on the basis of different levels of culpability and different circumstances i. Distinction between murder and manslaughter is not congruent with the distinction between intentional and unintentional ii. Not all intentional killing is murder (i.e. self defense) iii. Malice Aforethought 1. A traditional idea that you won’t see in modern statutes. 2. Term of art created by common law that provides the dividing line between more serious homicides from less serious ones—separates murder from manslaughter 3. Does not have a precise meaning, but can be described as “intention to cause or willingness to undertake a serious risk of causing the death of another, when that intent or willingness is based on an immoral or unworthy aim.” 4. Doesn’t necessarily include premeditation, but can. 5. Includes anger, hatred, revenge and every other unlawful and unjustifiable motive 6. Implied by any deliberate or cruel act against another 7. Malice aforethought (above the line) includes: a. Intentional murder: i. Intent to kill b. Unintentional murder: i. Intent to do serious bodily harm ii. Knowledge that death or serious bodily harm will likely occur iii. Depraved heart (unintentional homicide involving “extreme recklessness with regard to a serious risk to human life) iv. Felony-murder II. 8. Homicides that don’t include malice aforethought (below the line) a. Voluntary manslaughter (heat of passion) b. Involuntary manslaughter i. Violation of an objective standard (recklessness or negligence) 1. In some jurisdictions, violations of an objective standard are reckless killings other than the depraved heart kind 2. In some jurisdictions, vehicular homicide is a separate category ii. Misdemeanor manslaughter iii. Negligent homicide (MPC) iv. Premeditation 1. Dividing line between 1st and 2nd degree murder a. Many states do not have two degrees b. Some states have 3rd degree murder c. Usually there is no unintentional 1st degree murder unless it is felony murder 2. Qualitative vs. Quantitative view of premeditation: a. Quantitative: How much time is required i. The implication of the term is that some period of time is required to premeditate, but no court has given a bright-line rule about how much time is required for premeditation b. Qualitative: How much do you have to think before you do it i. Other courts focus on whether it was cold-blooded or committed with a second thought ii. Usually, courts can’t get around looking at the time factor c. Special homicides i. Common-law rule is that suicide is homicide ii. Statutes typically deal with the killing of law enforcement officers differently d. Different state statutes on homicides i. Typically idiosyncratic in that different states define the kinds of homicides differently ii. Some define the type of homicide based on who the victim is (i.e. police officer) iii. Legislatures find situations that are out of the ordinary and then treat them in a special way Murder a. Intentional i. In Georgia, malice murder = intentional murder 1. MPC 210.2: “Except as provided in Section 210.3(1)(b), criminal homicide constitutes murder when: a. It is committed purposely or knowingly; or b. It is committed recklessly under circumstances manifesting an extreme indifference to the value of human life.” Such reckless and indifference are presumed if the actor is engaged or is an accomplice in the commission of, or an attempt to commit, or flight after committing or attempting to commit robbery, rape or deviate sexual intercourse by force or threat of force, arson, burglary, kidnapping or felonious escape.” ii. Premeditated murder—First degree 1. Historically, the line of premeditation distinguished between capital murder and murder resulting in a prison sentence. The courts then decided there couldn’t be a crime that automatically resulted in capital punishment. 2. Where a jurisdiction divides murder into 1st and 2nd degrees, premeditation distinguishes between the two a. The line between premeditation and intentional is fuzzy b. Trend is to go away from this approach 3. Some courts use qualitative terms (see above) a. Thought before actions b. Considered and reflected upon a preconceived act c. D gave killing a second thought d. Done in cold blood 4. Other courts speak in quantitative terms (see above) a. D had time to think about the crime i. Not a bright-line test because premeditation can occur in an instant depending on how much time is required iii. Transferred intent: 1. If the intent is to kill a human being, mistake is no defense 2. If D intends to shoot A but winds up killing B, he can be convicted for murdering B and attempting to murder A iv. Franklin: D, who had escaped from custody, shot (gun went off) victim through door while trying to get car keys. Court ruled that the instructions were flawed due to two maxims that required the jury to find malice if they found he fired the gun, alleviating the state’s burden. 1. Two maxims: a. Sane people who do things do them voluntarily b. Most people intend the natural and probable consequences of their voluntary acts 2. But, people do things where they don’t intend the consequences a. Double-decker bus driver v. Myers: Court ruled that there had to be intent to kill and malice. As a result, 62 inmates won retrials and the court eventually reversed itself. 1. Intent is typically a code word or translation of malice. b. Unintentional (Reckless/depraved heart murder or felony murder) i. Reckless/depraved heart murder: 1. Some recklessness is so extreme that we consider those who engage in such conduct to be murderers a. Intent to do serious bodily harm (where death results) b. Knowledge that death or grievous harm will occur c. MPC defines it as “extremely recklessly killing under circumstances of extreme indifference to value of human life” 2. Examples: a. Playing Russian roulette or poker b. Nanny shaking baby to death c. Medical murders such as giving a massive overdose of anesthesia or failing to monitor a patient’s condition d. Not properly maintaining murderous animals such as pit bulls trained to fight 3. Mayes: D threw beer glass at wife who was carrying an oil lamp. Court upheld the conviction for reckless murder because he acted with an abandoned and malignant heart. (MPC would say it was an extreme disregard for human life) ii. Felony murder 1. A killing committed in either perpetration of or an attempt to perpetrate a felony 2. What is required: a. Needs to be part of the felony as “one continuous transaction”—the killing need not have occurred while committing the felony i. Some causal connection between the felony and the killing ii. Hypo: Bank robber driving carefully down the street after leaving the bank is not guilty of felony murder if a child darts out in front and is killed b. Some jurisdictions require that the killing be done in furtherance of the felony c. Some jurisdictions use the identity of the victim i. If the victim is an innocent bystander—felony murder ii. If the victim is a co-felon—not felony murder d. Neither causation nor foreseeability are required 3. Stamp: Victim had a heart attack after armed robbery. Court ruled that D could be convicted for murder on the basis of the commission of an inherently dangerous felony. 4. Effect of the felony murder rule a. Takes burden of proving a mens rea off of the prosecution so that something off the chart is turned into the most severe crime we have. b. State doesn’t have to prove foreseeability (if it did, then it would be negligence) c. In some states, D can be convicted of both murder and the predicate crime. d. In Georgia, D can only be convicted of one of the crimes. 5. Rationale for felony murder rule: a. When someone commits a felony, they have shown themselves to be a bad person—Felony mens rea includes malice aforethought b. Deterrence i. Discourages people from committing felonies ii. Even if people are not deterred, they are encouraged to commit felonies more carefully and safely c. Retribution i. People who kill during felonies act with the moral equivalent of a depraved heart murderer ii. MPC 210.2(1)(b): “…reckless and indifference are presumed if the actor is engaged or is an accomplice in the commission of, or an attempt to commit, or flight after committing or attempting to commit robbery, rape or deviate sexual intercourse by force or threat of force, arson, burglary, kidnapping or felonious escape.”—disguised felony murder. 6. Criticism of felony murder rule: a. Studies show that death rarely occurs in connection with non-dangerous (?) felonies b. Doesn’t work as a deterrent because people who commit crimes usually assume it won’t result in death c. Many felony murders could be successfully tried as depraved heart murders d. Violates the fundamental precept of mens rea and we should especially not make an exception for the most severe crime—murder e. There are felonies which are not dangerous (i.e. embezzlement) 7. Common law v. Modern approach a. Originally, all felonies except manslaughter were predicate felonies b. As more felonies have evolved, it became necessary to limit predicate felonies for felony murder to those that are inherently dangerous (i.e. killing during income-tax fraud is not felony murder) i. Test for determining dangerousness: 1. Objective: Is this felony likely to create serious harm to others in general? 2. Subjective: Is there a high probability that this particular felony caused by this particular D will cause serious harm? ii. Problem with test for dangerousness: 1. Danger of post-hoc rationale—reasoning backwards so that since someone is dead, it must have been dangerous 2. Can’t really calculate the likelihood of death iii. Court’s interpretation is going to be guided by how it feels about the felony murder rule 8. Current state of felony murder laws a. Almost every state has some version of felony murder, but the trend has been to abolish or modify this rule (i.e. by limiting it to a list or inherently dangerous felonies) b. Different approaches/Limitations on scope of rule i. Type of felony: Some jurisdictions have statutes that enumerate specific felonies as predicates for the rule (i.e. theft, rape, robbery, etc.) ii. Time frame: Must be in furtherance of, in the course of, the felony iii. Other jurisdictions state that only “inherently dangerous” felonies are predicates for felony murder. 1. Gives wiggle room for discretion 2. Also creates problem of deciding what is inherently dangerous—in every felony murder case, it WAS in fact dangerous 3. Can limit it to mean that a deadly weapon was involved 9. Co-felons a. Accomplices are responsible for the acts of their co-felons b. If the co-felon shoots and kills someone during the crime, the other(s) are subject to felony murder charges as well c. If one felon kills his co-felon, the rule does not apply in some states 10. Augmentation of liability: In some jurisdictions, felony murder elevates liability 11. Merger rule: Killing merges with the predicate felony to make D criminally liable for the predicate felony only (i.e. the killing that results from manslaughter is still manslaughter) a. When the purpose of the underlying felony is to kill or seriously harm someone, felony murder cannot merge with that felony to create a more culpable killing. b. The predicate felony must be dangerous enough for the rule to apply, but not so dangerous that it would cause death or serious bodily harm in itself c. Can’t have aggravated assault or voluntary manslaughter as predicate felonies i. Child abuse—some courts say it is not inherently dangerous, others say it is so dangerous that it falls under the merger rule d. Moran: D killed police officers. Court ruled that the aggravated assault against each cope merged into the killing of each (think of them as separate). 12. Other ways to limit felony murder rule a. Get rid of it all together, there are plenty of ways to prove murder b. Only allow it outside of strict liability so that some independent level of culpability must be shown with regard to the killing c. Requiring that D act recklessly while committing a felony to raise it to murder III. Manslaughter a. Voluntary i. Intentional homicide that lacks malice and the killer either acted in the heat of passion after “adequate provocation” or acted in an honest but unreasonable belief the killing was necessary for self-defense. 1. Distinct from intentional murder in that it lacks malice aforethought (it is below the line) 2. Heat of passion requires that there cannot be a “cooling off period” 3. Walker: D killed man who was trying to get him to gamble and then drew a knife on him and his friends. Court reversed the conviction for murder and directed a verdict of voluntary manslaughter. ii. MPC 210.3(1): “Criminal homicide constitutes manslaughter when… 1. (a) a homicide which would otherwise be murder is committed under the influence of extreme mental or emotional disturbance for which there is no reasonable explanation or excuse. The reasonableness of such explanation or excuse shall be determined from the viewpoint of a person in the actor’s situation under the circumstances as he believes them to be.” 2. This is somewhat different from the traditional definition a. Uses the word “reasonable” b. “Extreme mental or emotional disturbance” replaces “heat of passion”— might broaden the window to include such things as stress, etc. c. Talks about D’s perspective d. Focuses on D and excuses rather than provocation e. Not a question of whether victim brought it on himself, but rather if we understand why D did what he did 3. Notice that the focus on D brings up the question: What is included in his “situation” a. Age, sex, personality, race. i. Kurtz says race can have two impacts: 1. Generalize people into stereotypes—all Jewish people are excitable 2. How it played into the individual’s reaction to something—A racial slur is going to affect someone who is that race differently than someone from outside the race ii. Gender raises the issue of stereotypes like men being hot-blooded and women being unreasonable b. MPC’s comments say it is ambiguous on purpose and leaves it open for the jury to decide which factors matter iii. GA statute: “Sudden violent and irresistible passion resulting from serious provocation.” iv. D is typically arguing voluntary manslaughter as a defense against a charge for murder 1. Kind of a compromise because otherwise it is murder on the one hand and acquittal on the other. 2. Three ways in which this may work as an argument on appeal: a. D presents voluntary manslaughter evidence but trial court refuses to instruct on it b. D presents voluntary manslaughter evidence but trial court instructs incorrectly c. D presents voluntary manslaughter evidence, the instruction is correct, but no reasonable jury would have found murder (problem alleged in Walker) 3. This compromise can be described as partial justification or partial excuse a. Justification: D was a little right for killing the guy b. Excuse: D did a bad thing, but it could be understood at least a little bit 4. Note that if the judge gives the wrong kind of pro-D instruction it can become difficult on appeal. a. Hypo: Judge Chauvinist instructs the jury that heat of passion always occurs when a man finds his wife having relations with another. i. If D is acquitted, it won’t go to the appeals court ii. If D is convicted of voluntary manslaughter, he likely won’t appeal iii. But if D is convicted of murder, he can’t complain about the voluntary manslaughter instruction on appeal v. Provocation 1. Objective AND subjective standard required a. An ordinary person must have been provoked in same situation (adequate) b. This particular D must have been provoked (actual) 2. Common law approach: a. Provided certain circumstances when provocation could occur because the ordinary person would be provoked under the circumstances—pigeon hole approach i. Fighting ii. Assault and battery iii. Seeing one’s wife in adultery or a narrative about it (honor defense) iv. NOT words 3. Modern law approach/Reformed rules: a. A question of provocation will go to the jury (see Berry case below) i. Designed to send more cases to the jury b. But the judge still has a role in that he could say there is no way a reasonable jury could find it was a reasonable provocation and thus it won’t go to the jury. i. Hypo: D kills someone for wearing a Cubs hat instead of a Yankees hat. Judge could decide a jury could not possibly find this to be sufficient provocation. ii. Nourse article argues this new approach is still too relaxed—slippery slope c. Must be adequate—if a reasonable person would lose self-control and actual—this D lost self-control 4. Rowland: D killed his wife after catching her with another man. Court ruled that this was adequate provocation and reversed the murder conviction. a. (Es) brevis furor: “Anger is short madness” 5. Mistake (with regard to provocation) a. Majority view—Mistake of fact is a defense if there is a reasonable belief and that is what excites the heat of passion i. Example: D kills man he reasonably believes just had sex with his wife, but it turns he’s wrong b. Minority view—Mistake of fact is not a defense i. Example: They would actually have to be having an affair for D to get a voluntary manslaughter instruction 6. Gradual/Cumulative provocation a. Sudden anger is not cumulative by definition and thus, gradual or cumulative provocation is usually not sufficient for heat of passion i. Supported by the idea that we want to encourage people to seek other ways of carrying out their emotions ii. The longer we let it go, the harder it is to have evidence of the initial provocation iii. Gives the victim a chance to rehabilitate or be forgiven iv. Gounagias: Man sodomized D and then went around telling people. Court ruled that it was not a heat of passion killing but rather “brooding thought, resulting in the design to kill.” v. But note that the modern idea of send-cases-to-the-jury has come into play on this idea: 1. Berry: D killed wife who taunted him after she went to Israel, found lover, and wouldn’t stop screaming during their fight. Court ruled that jury could decide if provocation was sufficient, ignoring the cumulative aspects of the situation. vi. Cooling time 1. Objective AND subjective standard required a. An ordinary person must have lacked cooling time in same situation b. This particular D must have lacked cooling time 2. Traditional view a. When homicide occurs after an unreasonable period of time has elapsed since provocation, there was sufficient cooling time (to constitute murder) i. Can’t have cumulative provocation 1. Manslaughter is something sudden and not something that results from a series of events ii. Want people to seek other means to deal with emotions 3. Fraley: D killed man who allegedly killed his son 9 or 10 months ago. Court ruled the amount of time that had passed was sufficient cooling time and upheld the charge of murder. a. D may have passed the subjective test, but not the objective test. You need BOTH. b. Outcome might have been different if this was the first time he saw the victim. vii. Rationale for voluntary manslaughter 1. Less culpable than a murderer (compromise) 2. Not as criminal as murder 3. D thought he was at least a little right to kill or had a reason to kill 4. Victim “deserved” it a. Under tort law, this would be assumption of the risk viii. Theories of punishment (why we punish this less than murder) 1. Deterrence: People won’t be deterred more when they are acting on the spur of the moment if there is more punishment 2. Retribution: Punish less because less culpable 3. Rehabilitation: Not as necessary because of the extreme circumstances 4. Incapacitation: Again, not as necessary because of the extreme circumstances ix. Reasonable person standard: 1. An average person acting under same or similar circumstances a. Age is a factor for consideration i. 15-year-old should be held to standard of reasonable person of his age b. Not clear whether gender, race, education should be taken into consideration i. Perhaps if it has something to do with provocation, it might c. Can’t make it too subjective d. MPC—jury determines whether it was reasonable in the actor’s situation b. Involuntary (Unintentional homicide committed recklessly or highly negligently) i. Two types: 1. Felony manslaughter(?)—violation of an objective standard a. Reckless or negligence (note that earlier, we said reckless was a subjective standard) i. MPC carves out a separate category for negligent homicide. b. Involves a disregard or ignorance of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that death or serious bodily injury might occur (not as extreme as involuntary murder requires) i. Some jurisdictions add a separate category for vehicular homicide 2. Misdemeanor manslaughter a. Junior version of felony murder—non-predicate felony manslaughter b. Difference between dangerous felonies and non-dangerous felonies ii. Culpability requirements 1. Split of authority: a. Some jurisdictions include both negligent and reckless killings under involuntary manslaughter b. Other jurisdictions make distinctions between negligent and reckless killings c. Others only say reckless 2. MPC makes a distinction between negligence, recklessness, and extreme recklessness a. Negligence is manslaughter (210.4) i. 3rd degree felony b. Recklessness is manslaughter (210.3) c. Extreme recklessness is (depraved heart) murder (210.2(b)) 3. Criminal negligence a. Actor should have been aware of the risks (ignorant of the risks) b. D didn’t want or desire the result to happen c. D didn’t know it was going to happen d. Could be argued that D was not negligent at all because each of us would have acted the same way e. Psychology of negligence—major blunders can happen even to experts or the experienced when they are acting out of habit i. Example: Double-decker bus driving into bridge ii. Become conditioned because he is used to doing something a certain way 4. Reasons why we do hold people liable a. Retribution: Someone died b. Deterrence: We don’t want people acting on autopilot i. Same as strict liability argument where we want people to act extremely carefully 5. Welansky: D’s nightclub caught on fire (while he was somewhere else) and had inadequate exits so many were killed. Court ruled that the statute allowed a finding of negligence—even though they say it is reckless—for involuntary manslaughter and uphold the conviction. Rape I. II. III. Classroom a. Difficult to talk about i. The crime that has most likely affected some of us directly or indirectly ii. Just on the other side of something private and good b. How rape is a different kind of crime: i. Victim has experienced something different than other victims ii. Switches concerns so that those who are ordinarily concerned with D are concerned with the victim 1. Blue-collar, white-collar 2. Women are usually pro-D unless it is about rape iii. More controversial than it is clear-cut 1. Leads to classic “he said, she said” problem as it almost always occurs in a private place 2. One out of five incidents are not reported 3. Informally involves something potentially suspicious about the victim so that she has to defend herself in ways victims of burglary don’t 4. Racial issue polarizes us in these cases in a way other crimes don’t iv. Elements are confusing 1. Force and lack of consent are not identical a. No consent, no force—victim is passed out b. Force, but consent—S & M 2. But most cases show that if there was no consent, there was likely force and vice versa Developments in rape law a. Procedural barriers to conviction have come down: i. Time limitation for when report of rape had to made gone ii. No longer does victim have to have corroborating evidence iii. Practice of instructing jury that rape was easily charged but difficult to prove no longer allowed b. New barriers to make conviction easier: i. Rape shield laws prohibit D from admitting evidence about victim’s background (i.e. sexual history, way she was dressed) ii. “Proving” element has changed 1. No longer formally requires resistance to prove force or nonconsent 2. Force doesn’t require physical beating or threat 3. Some states have eliminated force requirement completely and make the failure to have an affirmative consent the requirement instead c. Scope of rape law has expanded: i. Marital exception no longer exists ii. Rape statutes have been made gender-neutral (not in Georgia) iii. The physical act of rape no longer requires penetration—sexual assault Typical Elements a. The sexual act IV. V. b. D acted forcibly c. Against victim’s will d. No explicit mens rea requirement MPC 2.13.1 a. Fairly traditional b. “A male who has sexual intercourse with a female not his wife is guilty of rape if: i. He compels her to submit by force or by threat of imminent death, serious bodily injury, extreme pain or kidnapping, to be inflicted on anyone; or ii. He has substantially impaired her power to appraise or control her conduct by administering or employing her without her knowledge drugs, intoxicants or other means for the purpose of preventing resistance; or iii. The female is unconscious; or iv. The female is less than 10 years old.” c. Pro-defendant— i. Stranger rape is 1st degree but date rape is 2nd degree ii. She can’t have slept with D before, be a social companion, be his wife, be mentally incapable iii. Requires prompt complaint and corroboration iv. Jury is instructed that victim’s testimony could be affected by her emotional involvement, even though they would not be told this in burglary or assault cases d. Pro-state— i. Doesn’t talk about resistance or nonconsent, just force ii. Threat can be directed against anyone (i.e. “I’ll kill your brother if you don’t sleep with me”) iii. Unconscious victim is explicitly mentioned Evolution of actus reus requirement—to show force a. Phase 1: Utmost resistance i. Law required “the most vehement exercise of every physical power to resist the penetration” 1. Insufficient resistance when the victim only tried to escape, but didn’t oppose the force 2. Based on the belief that a woman would risk life and limb to preserve her chastity— fighting to the very end 3. Puts up a guard to protect from the deceitful woman who cried rape when her fornication was discovered ii. Prof. Coughlin notes that the charge of rape was originally a defense for women who were charged with adultery or fornication 1. 19th century rape law was not intended to encourage sexual autonomy, but rather to confine it 2. In order to defend against the charge, a woman would have to show a. Lack of actus reus—was not voluntary b. Lack of mens rea—did not know it was not her husband or did not think she was having sex c. Duress—did it because she thought she would be hurt or killed iii. This requirement makes the victim have to gamble since her resistance can either discourage her attacker or encourage him to inflict more serious injury. iv. Brown: Court reversed conviction where victim didn’t protest beyond saying “let me go” because she was required to oppose force with force and show the “most vehement exercise of every physical power to resist.” b. Phase 2: Earnest resistance i. Resistance of a type reasonably to be expected from a person who genuinely refuses to participate in sex under all particular circumstances 1. Shows both force and lack of consent 2. Puts the burden on the victim to show resistance or the futility of resistance ii. Dorsey: Woman was raped by taller, bigger man in elevator—no actual resistance, no verbal threat, she didn’t say “no” and took off her own clothes. Court affirmed conviction because a jury could have found she used reasonable resistance under the circumstances. VI. iii. Powell: Court said she did not consent, but did not reasonably resist. Shows that the burden is on the victim to do something. c. Phase 3: Forcible compulsion: i. Legal rejection of resistance requirement, so that elements of rape become the combination of force and nonconsent 1. Resistance may still help establish force, but it is not necessary to prove force 2. Pro-state way of looking at rape ii. Reasons for abandoning the resistance requirement 1. A woman can not resist and still not be consenting 2. People react differently in particular situations—psychological infantilism like freezing, etc. 3. Resistance can be dangerous to resist by increasing the risk of injury 4. State is unwilling to file cases with no resistance iii. State only has to prove force and nonconsent 1. Victim must fear immediate and unlawful bodily injury iv. Barnes: Victim was buying marijuana from D when wouldn’t let her leave and physically threatened her. Court abandoned the resistance requirement and upheld conviction. v. Prof. Anderson argues for retaining the resistance element: 1. There are so few really dangerous rapes that we ought to encourage people to resist 2. Resistance will deter people from rape 3. Problems with her argument: a. Resistance can turn a bad rape into a really dangerous rape b. Makes women responsible for resistance (puts burden on victim) d. Phase 4: Nonconsent i. Most jurisdictions have reached this point ii. Under this view, force is not considered at all. iii. State only has to prove that the sex was not consented to 1. To see if there is consent, focus on the victim’s behavior from D’s eyes—would it have reasonably appeared to a reasonable D that she was consenting? iv. Prof. Dripps says we spend too much time arguing about consent when we should be looking at: 1. Sexually motivated assault—purposely or knowingly putting victim in fear of violence for purpose of causing sexual submission 2. Sexual expropriation—sexual act over verbal protest of victim without purposely or knowingly putting her in fear of physical injury v. Prof. West says this a bad argument because there is violence in all rape and depriving someone of sexual autonomy is just as bad as threatening to kill someone. vi. Smith: D forced himself on victim after their date and she eventually gave in. Court ruled that consent depended on how her manifestation of such consent was reasonably construed and upheld the conviction because her ultimate lack of resistance was clearly not consent. 1. D should have known she was not consenting—negligence e. Phase 5: Lack of an affirmative expression of consent i. Few jurisdictions have gone this far ii. State only has to prove that there is no explicit expression of consent 1. Doesn’t necessarily mean that they have to be written or spoken 2. Consent can be manifested through behavior iii. Failure to say “yes” means “no” iv. State Ex Rel. M.T.S: D went into girl’s bedroom and when she woke up he was having sex with her. Court upheld conviction because she failed to say yes. Mens rea requirement a. Most courts leave this out of their discussion of rape i. D usually denies the actus reus ii. Some cases have raised the mens rea issue b. Traditionally, the requirement of force showed that D had the requisite mens rea i. If he knew she didn’t want to have sex, he must have had the mens rea for rape ii. If D jumped to a defense of lack of mens rea, he was conceding the actus reus 1. D first says she consented, but in the alternative that he believed she was consenting and should have a defense a. In England, House of Lords has said that the mens rea for rape is intent to have unconsented sex b. Some courts have held that purpose or knowledge (or at least recklessness) is required with regard to nonconsent c. Other courts have implicitly held that there is no mens rea requirement c. Public policy debate i. Prof. Estrich says courts should require a mens rea and allow reasonable mistake so that if it’s off the chart (below negligence), he has a defense 1. It will benefit victims because it will take the focus off the victim and will allow juries who would be unwilling to convict D who did not act recklessly or knowingly with regard to nonconsent but who did act negligently 2. The current system focuses too much on the victim and intentional D are acquitted because victim was feigning consent and he knew she was. ii. Prof. Henderson, disagreeing with Estrich, says that explicitly requiring mens rea with regard to nonconsent will open the door to looking at victim’s history and behavior—focus on victim 1. D could argue that he thought she consented because they had a previous sexual relationship, she behaved a certain way, etc. 2. Reasonable mistake will only get us into the issue of what is “reasonable” to men and women (might be different things)—and that it will likely end up being the male version which favors D and not the victim d. Fischer: D and victim had sexual history involving “rough sex.” Court said he could not have a mistake of fact defense with regard to her consent because the legislature had not given him one. Attempt I. Generally a. A chameleon crime in that it always takes on the “color” of whatever substantive crime it is attached to—attempt in the abstract means nothing i. An inchoate/unfinished or undeveloped crime where the ultimate harm has not occurred 1. Hypo: Man standing outside Brooks hall with a lit match and a note on his shirt saying he is going to set the building on fire ii. No single crime of attempt—always attached to another crime b. Reasons for punishing attempt i. People who are trying to commit a crime have shown themselves to be dangerous ii. Preemptively stops people from committing the ultimate crime 1. If not, we would have to wait until the commission of the full crime was complete before punishing iii. Wouldn’t be fair to let someone go just because they happened to fail to commit the full crime 1. Shooting at someone and missing is just as bad of an act as if the bullet hits them c. Why punish less than for the ultimate crime? (MPC says to punish it the same) i. Person who killed is really worse than the one who didn’t commit the crime 1. Tells us that results count ii. Should be extra punishment for the completion of the crime iii. If we punish too much the jury won’t convict when they think it is unfair iv. To provide an incentive for the criminal to turn back before committing the crime 1. If it is punished at the same level, there is no reason to turn back d. Two kinds of attempt i. Screw-up: Shoot and miss ii. Actus interruptus: Shooter is tackled before he shoots (getting caught while trying) e. GA statute §16-4-1: A person commits the offense of criminal attempt when, with the intent to commit a specific crime, he performs any act which constitutes a substantial step toward the commission of that crime. II. III. Mens rea a. Majority view is that attempt requires intent (purpose) to commit the acts that constitute the crime i. D must intend to commit the act he committed and intend to commit the substantive crime ii. Why require a higher level mens rea? 1. Makes up for a low actus reus requirement 2. Want to make sure that D is a dangerous person since he is for all intensive purposes “innocent” iii. No such thing as attempted result crime 1. Cannot attempt involuntary manslaughter or reckless homicide because you don’t intend that someone die in those instances 2. Lyerla: D fired at pickup truck and killed one passenger, but was convicted of attempted second degree murder for other two. Court reversed attempt conviction because you cannot intend to act recklessly. (Can’t intend that someone dies—the result element of the crime—with a reckless state of mind) iv. Can attempt reckless behavior crimes 1. Can attempt to recklessly drive v. MPC gloss says D doesn’t have to intend with regard to circumstance elements, only what the crime required. 1. b. Minority view is that attempt doesn’t require purpose, but rather only requires that D acted voluntarily i. Says that the majority view creates a gap where if you act in any way less than intentionally and come close to causing harm, your acts are not punishable. ii. MPC tries to fill this gap with reckless endangerment. c. MPC 5.01: “A person is guilty of an attempt to commit a crime if, acting with the kind of culpability otherwise required for commission of the crime, he: i. Purposely engages in conduct that would constitute the crime if the attendant circumstances were as he believes them to be; or ii. When causing a particular result is an element of the crime, does or omits to do anything with the purpose of causing or with the belief that it will cause such result without further conduct on his part; or iii. Purposely does or omits to do anything which, under the circumstances as he believes them to be, is an act or omission constituting a substantial step in a course of conduct planned to culminate in his commission of the crime.” Actus reus a. Four approaches to tell where to draw the line between preparation and attempt: i. Proximity: focuses on the nearness of what has been done toward the ultimate crime—if it is close enough, sufficient for actus reus (want to be sure there was a dangerous act before we try to stop it) 1. The last proximate act a. D must have committed the last act necessary to commit the ultimate crime b. Most pro-D approach c. Excludes all the crimes of actus interruptus d. Example: Point the gun and pull the trigger, but didn’t kill i. NOT: 1. Giving 8 of 9 doses of poison 2. Pointing the gun 2. Physical proximity a. D must have been physically close to the ultimate crime b. Example: Trying to find the bank manager that had money, but never actually found him—no physical proximity 3. Dangerous proximity a. Combines an analysis of how dangerous the crime is and how close D came to committing it 4. Indispensable element a. In most crimes there is something that can be identified as indispensable to the commission of the ultimate crime b. Example: When committing loan fraud, having the form filled out fraudulently ii. Probable desistance: 1. D has reached the point at which it is unlikely he will return 2. Premise behind this approach is that people return all the time and the actus reus is supposed to separate the dangerous people from the not-so dangerous people 3. Focuses on what has been done rather than what remains to be done 4. Finds the dangerous person before physical proximity or the last act 5. Critics say this approach is artificial and imprecise iii. Equivocality (res ipsa loquitur or the thing speaks for itself) 1. An unequivocal act has been committed 2. Not going to find an actus reus of attempt without it being very obvious to anybody of what was going on 3. A bright-test by definition 4. Focuses on what has been done 5. Assures an evil intent 6. Criticisms: a. Acts rarely speak from themselves short of the last act b. If we wait for the last act, we’ve waited too long c. It may look like attempt, but is really something innocent i. Brooks hall hypo: lighting a match is not illegal iv. MPC approach 5.01(1) 1. “Purposely engages in conduct that would constitute the crime if the attendant circumstances were as he believes them to be…” a. Sounds like he has already done the crime—looks like last act approach 2. “When causing a particular result is an element of the crime, does or omits to do anything with the purpose of causing or with the belief that it will cause such result without further conduct on his part” a. Talks about result element—looks like last act approach 3. “Purposely does or omits to do anything which, under the circumstances as he believes them to be, is an act or omission constituting a substantial step in a course of conduct planned to culminate in his commission of the crime.” a. Substantial step involves conduct that is strongly corroborative of the actor’s criminal purpose b. Can fit in with the idea of the actus interruptus c. Pro-state kind of test i. Doesn’t sound like you necessarily mean you have to get to the last act ii. Doesn’t require physical proximity, dangerousness, etc. but just a substantial step d. Can argue D-oriented aspect i. Under prior test, state had to prove proximate act, an act which spoke for itself, or an act beyond the point of probable return ii. Under this test, state has to prove a substantial step and that it is strongly corroborative 1. Strongly corroborative, but not substantial—tell everyone you’re going to kill the dean 2. Substantial step, but not corroborative—walk into dean’s office twirling a loaded gun b. Defenses to attempt i. Abandonment 1. After the actus reus of attempt has been committed, D abandons his attempt a. Split authority on whether this is allowed as a defense—most don’t allow it 2. Must be complete and voluntary a. D cannot get abandonment defense if he did it because he realized he was about to get or screwed up 3. Arguments for allowing it as a defense a. Gives D an incentive to turn back b. Attempt is about purpose and D turning back casts doubt on his intent to begin with—many states doubt this ii. Impossibility 1. If D has committed some mistake by which it is impossible for him to commit the crime, some states allow a defense 2. Generally, legal impossibility is a defense but factual impossibility is not a. Distinction between the two is unclear b. MPC and Kurtz would solve the problem by looking at whether D intended to commit acts we consider to be criminal i. IF D buys a coat he thinks it stolen, whether it was actually a legally classified as a “stolen good” should not matter because he intended to buy stolen goods. 3. Three special situations: (Kurtz only likes the third) a. Inherent impossibility i. D’s attempt to kill someone with voodoo 1. From D’s perspective, he committed the last act necessary for the ultimate crime. 2. MPC would allow conviction for attempted murder, but since the conduct is unlikely to result in a criminal act it will not be b. Neutral act i. D shoots stuffed deer out-of-season 1. State could say he’s attempting to hunt, but D could argue he’s doing target practice 2. MPC would allow conviction if his intent was to commit a crime, but it’s hard to determine that under these facts c. Fictional crime i. D thinks it is a crime to commit mopery and does so 1. No DA will take this to court because it isn’t a crime to mope 2. Ignorance of the law is no defense (for everyone)