Total Quality

Management (TQM)

This image is hidden. Click

to adjust visibility.

Add

Image

Add

Video

Advertisement

Related Terms: ISO 9000; Quality Circles; Quality Control

Total Quality Management (TQM) refers to management methods used to enhance

quality and productivity in business organizations. TQM is a comprehensive management

approach that works horizontally across an organization, involving all departments and

employees and extending backward and forward to include both suppliers and

clients/customers.

TQM is only one of many acronyms used to label management systems that focus on

quality. Other acronyms include CQI (continuous quality improvement), SQC (statistical

quality control), QFD (quality function deployment), QIDW (quality in daily work), TQC

(total quality control), etc. Like many of these other systems, TQM provides a framework

for implementing effective quality and productivity initiatives that can increase the

profitability and competitiveness of organizations.

Home

Knowledge

Competency Framework

Qualifications

Training

Membership

Community

The CQI

My CQI

Home>Knowledge>Tools and resources>Factsheets>Total quality management (TQM)

Research and reports

ISO 9001:2015 Review

Body of Knowledge

Tools and resources

o Journal of Quality

o Quality Survival Guide

o Small business standard

o Video library

o Factsheets

Introduction to quality

Selecting a certification body

Total quality management (TQM)

Quality awards

Integrated management systems

Continual improvement

Quality World magazine

Quality Express newsletter

Find a consultant

Find an auditor

Careers in quality

Find a job

Total quality management (TQM)

Total quality management is a management approach centred on quality, based on the

participation of an organisation's people and aiming at long term success (ISO

8402:1994). This is achieved through customer satisfaction and benefits all members of

the organisation and society.

In other words, TQM is a philosophy for managing an organisation in a way which

enables it to meet stakeholder needs and expectations efficiently and effectively, without

compromising ethical values.

TQM is a way of thinking about goals, organisations, processes and people to ensure that

the right things are done right first time. This thought process can change attitudes,

behaviour and hence results for the better.

What TQM is not

TQM is not a system, a tool or even a process. Systems, tools and processes are

employed to achieve the various principles of TQM.

What does TQM cover?

The total in TQM applies to the whole organisation. Therefore, unlike an ISO 9000

initiative which may be limited to the processes producing deliverable products, TQM

applies to every activity in the organisation. Also, unlike ISO 9000, TQM covers the soft

issues such as ethics, attitude and culture.

What is the TQM philosophy?

There are several ways of expressing this philosophy. There are also several gurus whose

influence on management thought in this area has been considerable, for example

Deming, Juran, Crosby, Feigenbaum, Ishikawa and Imai. The wisdom of these gurus has

been distilled into eight principles defined in ISO 9000:2000.

The principles of quality management:

There are eight principles of quality management:

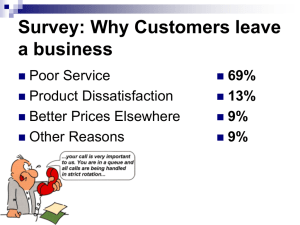

customer-focused organisation - organisations depend on their customers and

therefore should understand current and future customer needs, meet customer

requirements and strive to exceed customer expectations

leadership - leaders establish unity of purpose, direction and the internal

environment of the organisation. They create the environment in which people

can become fully involved in achieving the organisation's objectives

involvement of people - people at all levels are the essence of an organisation and

their full involvement enables their abilities to be used for the organisation's

benefit

process approach - a desired result is achieved more efficiently when related

resources and activities are managed as a process

system approach to management - identifying, understanding and managing a

system of interrelated processes for a given objective contributes to the

effectiveness and efficiency of the organisation

continual improvement - continual improvement is a permanent objective of an

organisation

factual approach to decision making - effective decisions are based on the logical

and intuitive analysis of data and information

mutually beneficial supplier relationships - mutually beneficial relationships

between the organisation and its suppliers enhance the ability of both

organisations to create value

How does TQM differ from the EQA model?

The European Quality Award model is used to assess business excellence. Business

excellence is the result of adopting a TQM philosophy and realigning the organisation

towards satisfying all stakeholders (customers, owners, shareholders, suppliers,

employees and society). The quality award criteria offers measures of performance rather

than a methodology.

Why should a company adopt TQM?

Adopting the TQM philosophy will:

make an organisation more competitive

establish a new culture which will enable growth and longevity

provide a working environment in which everyone can succeed

reduce stress, waste and friction

build teams, partnerships and co-operation

When should a company adopt TQM?

TQM can be adopted at any time after executive management has seen the error of its

ways, opened its mind and embraced the philosophy. It cannot be attempted if

management perceives it as a quick fix, or a tool to improve worker performance.

How should a company adopt TQM?

Before TQM is even contemplated

TQM will force change in culture, processes and practice. These changes will be more

easily facilitated and sustained if there is a formal management system in place. Such a

system will provide many of the facts on which to base change and will also enable

changes to be implemented more systematically and permanently.

The first steps

In order to focus all efforts in any TQM initiative and to yield permanent benefits, a

company must answer some fundamental questions:

what is its purpose as a business?

what is its vision for the business?

what is its mission?

what are the factors upon which achievement of its mission depends?

what are its values?

what are its objectives?

A good way to accomplish this is to take top management off site for a day or two for a

brainstorming session. Until management shares the same answers to these questions and

has communicated them to the workforce there can be no guarantee that the changes

made will propel the organisation in the right direction.

Methodology

There are a number of approaches to take towards adopting the TQM philosophy. The

teachings of Deming, Juran, Taguchi, Ishikawa, Imai, Oakland etc can all help an

organisation realign itself and embrace the TQM philosophy. However, there is no single

methodology, only a bundle of tools and techniques.

Examples of tools include:

flowcharting

statistical process control (SPC)

Pareto analysis

cause and effect diagrams

employee and customer surveys

Examples of techniques include:

benchmarking

cost of quality

quality function deployment

failure mode effects analysis

design of experiments

Measurements

After using the tools and techniques an organisation needs to establish the degree of

improvement. Any number of techniques can be used for this including self-assessment,

audits and SPC.

Pitfalls

TQM initiatives have been prone to failure because of common mistakes. These include:

allowing external forces and events to drive a TQM initiative

an overwhelming desire for quality awards and certificates

organising and perceiving TQM activities as separate from day-to-day work

responsibilities

treating TQM as an add-on with little attention given to the required changes in

organisation and culture

senior management underestimating the necessary commitment to TQM

CQI Members

Please log in to access your CQI member services, update your details and pay

subscriptions.

Log in

See Also

Total quality

Print page

Add to Favorites

Save to...

Digg

De.licio.us

Facebook

Google Bookmarks

Reddit

Stumbleupon

Contact the CQI

Terms and conditions

Privacy Policy

Accessibility

Sitemap

Incorporated by Royal Charter and registered as a charity number 259678

© 2014 the CQI. All Rights Reserved. This website uses cookies, please view our

Privacy Policy

v1.0.0.9

ORIGINS

TQM, in the form of statistical quality control, was invented by Walter A. Shewhart. It

was initially implemented at Western Electric Company, in the form developed by Joseph

Juran who had worked there with the method. TQM was demonstrated on a grand scale

by Japanese industry through the intervention of W. Edwards Deming—who, in

consequence, and thanks to his missionary labors in the U.S. and across the world, has

come to be viewed as the "father" of quality control, quality circles, and the quality

movement generally.

Walter Shewhart, then working at Bell Telephone Laboratories first devised a statistical

control chart in 1923; it is still named after him. He published his method in 1931 as

Economic Control of Quality of Manufactured Product. The method was first introduced

at Western Electric Company's Hawthorn plant in 1926. Joseph Juran was one of the

people trained in the technique. In 1928 he wrote a pamphlet entitled Statistical Methods

Applied to Manufacturing Problems. This pamphlet was later incorporated into the

AT&T Statistical Quality Control Handbook, still in print. In 1951 Juran published his

very influential Quality Control Handbook.

W. Edwards Deming, trained as a mathematician and statistician, went to Japan at the

behest of the U.S. State Department to help Japan in the preparation of the 1951 Japanese

Census. The Japanese were already aware of Shewhart's methods of statistical quality

control. They invited Deming to lecture on the subject. A series of lectures took place in

1950 under the auspices of the Japanese Union of Scientists and Engineers (JUSE).

Deming had developed a critical view of production methods in the U.S. during the war,

particularly methods of quality control. Management and engineers controlled the

process; line workers played a small role. In his lectures on SQC Deming promoted his

own ideas along with the technique, namely a much greater involvement of the ordinary

worker in the quality process and the application of the new statistical tools. He found

Japanese executive receptive to his ideas. Japan began a process of implementing what

came to be known as TQM. They also invited Joseph Juran to lecture in 1954; Juran was

also enthusiastically received.

Japanese application of the method had significant and undeniable results manifesting as

dramatic increases in Japanese product quality—and Japanese success in exports. This

led to the spread of the quality movement across the world. In the late 1970s and 1980s,

U.S. producers scrambled to adopt quality and productivity techniques that might restore

their competitiveness. Deming's approach to quality control came to be recognized in the

United States, and Deming himself became a sought-after lecturer and author. Total

Quality Management, the phrase applied to quality initiatives proffered by Deming and

other management gurus, became a staple of American enterprise by the late 1980s. But

while the quality movement has continued to evolve beyond its beginnings, many of

Deming's particular emphases, particularly those associated with management principles

and employee relations, were not adopted in Deming's sense but continued as changing

fads, including, for example, the movement to "empower" employees and to make

"teams" central to all activities.

TQM PRINCIPLES

Different consultants and schools of thought emphasize different aspects of TQM as it

has developed over time. These aspects may be technical, operational, or

social/managerial.

The basic elements of TQM, as expounded by the American Society for Quality Control,

are 1) policy, planning, and administration; 2) product design and design change control;

3) control of purchased material; 4) production quality control; 5) user contact and field

performance; 6) corrective action; and 7) employee selection, training, and motivation.

The real root of the quality movement, the "invention" on which it really rests, is

statistical quality control. SQC is retained in TQM in the fourth element, above,

"production quality control." It may also be reflected in the third element, "control of

purchased material," because SQC may be imposed on vendors by contract.

In a nutshell, this core method requires that quality standards are first set by establishing

measurements for a particular item and thus defining what constitutes quality. The

measurements may be dimensions, chemical composition, reflectivity, etc.—in effect any

measurable feature of the object. Test runs are made to establish divergences from a base

measurement (up or down) which are still acceptable. This "band" of acceptable

outcomes is then recorded on one or several Shewhart charts. Quality control then begins

during the production process itself. Samples are continuously taken and immediately

measured, the measurements recorded on the chart(s). If measurements begin to fall

outside the band or show an undesirable trend (up or down), the process is stopped and

production discontinued until the causes of divergence are found and corrected. Thus

SQC, as distinct from TQM, is based on continuous sampling and measurement against a

standard and immediate corrective action if measurements deviate from an acceptable

range.

TQM is SQC—plus all the other elements. Deming saw all of the elements as vital in

achieving TQM. In his 1982 book, Out of the Crisis, he contended that companies needed

to create an overarching business environment that emphasized improvement of products

and services over short-term financial goals—a common strategy of Japanese business.

He argued that if management adhered to such a philosophy, various aspects of

business—ranging from training to system improvement to manager-worker

relationships—would become far healthier and, ultimately, more profitable. But while

Deming was contemptuous of companies that based their business decisions on numbers

that emphasized quantity over quality, he firmly believed that a well-conceived system of

statistical process control could be an invaluable TQM tool. Only through the use of

statistics, Deming argued, can managers know exactly what their problems are, learn how

to fix them, and gauge the company's progress in achieving quality and other

organizational objectives.

MAKING TQM WORK

In the modern context TQM is thought to require participative management; continuous

process improvement; and the utilization of teams. Participative management refers to the

intimate involvement of all members of a company in the management process, thus deemphasizing traditional top-down management methods. In other words, managers set

policies and make key decisions only with the input and guidance of the subordinates

who will have to implement and adhere to the directives. This technique improves upper

management's grasp of operations and, more importantly, is an important motivator for

workers who begin to feel like they have control and ownership of the process in which

they participate.

Continuous process improvement, the second characteristic, entails the recognition of

small, incremental gains toward the goal of total quality. Large gains are accomplished

by small, sustainable improvements over a long term. This concept necessitates a longterm approach by managers and the willingness to invest in the present for benefits that

manifest themselves in the future. A corollary of continuous improvement is that workers

and managers develop an appreciation for, and confidence in, TQM over a period of time.

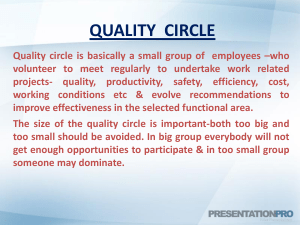

Teamwork, the third necessary ingredient for TQM, involves the organization of crossfunctional teams within the company. This multidisciplinary team approach helps

workers to share knowledge, identify problems and opportunities, derive a

comprehensive understanding of their role in the overall process, and align their work

goals with those of the organization. The modern "team" was once the "quality circle," a

type of unit promoted by Deming. Quality circles are discussed elsewhere in this volume.

For best results TQM requires a long-term, cooperative, planned, holistic approach to

business, what some have dubbed a "market share" rather than a "profitability" approach.

Thus a company strives to control its market by gaining and holding market share

through continuous cost and quality improvements—and will shave profits to achieve

control. The profitability approach, on the other hand, emphasizes short-term stockholder

returns—and the higher the better. TQM thus suits Japanese corporate culture better than

American corporate culture. In the corporate environment of the U.S., the short-term is

very important; quarterly results are closely watched and impact the value of stocks; for

this reason financial incentives are used to achieve short term results and to reward

managers at all levels. Managers are therefore much more empowered than employees—

despite attempts to change the corporate culture. For these reasons, possibly, TQM has

undergone various changes in emphasis so that different implementations of it are

sometimes unrecognizable as the same thing. In fact, the quality movement in the U.S.

has moved on to other things: the lean corporation (based on just-in-time sourcing), Six

Sigma (a quality measure and related programs of achieving it), and other techniques.

PRACTICING TQM

As evident from all of the foregoing, TQM, while emphasizing "quality" in its name, is

really a philosophy of management. Quality and price are central in this philosophy

because they are seen as effective methods of gaining the customer's attention and

holding consumer loyalty. A somewhat discriminating public is thus part of the equation.

In an environment where only price matters and consumers meekly put up with the

successive removal of services or features in order to get products as cheaply as possible,

the strategy will be less successful. Not surprisingly, in the auto sector, where the

investment is large and failure can be very costly, the Japanese have made great gains in

market share; but trends in other sectors—in retailing, for instance, where labor is

imposed on customers through self-service stratagems—a quality orientation seems less

obviously rewarding.

For these reasons, the small business looking at an approach to business ideal for its own

environment may well adapt TQM if it can see that its clientele will reward this approach.

The technique can be applied in service and retail settings as readily as in manufacturing,

although measurement of quality will be achieved differently. TQM may, indeed, be a

good way for a small business, surrounded by "Big Box" outlets, to reach precisely that

small segment of the consuming public that, like the business itself, appreciates a high

level of service and high quality products delivered at the most reasonable prices

possible.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Basu, Ron, and J. Nevan Wright. Quality Beyond Six Sigma. Elsevier, 2003.

Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis. MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study,

1982.

Juran, Joseph M. Architect of Quality. McGraw-Hill, 2004.

"The Life and Contributions of Joseph M. Juran." Carlson School of Management,

University of Minnesota. Available from http://parttimemba.csom.umn.edu/Page1275.aspx. Retrieved on 12 May 2006.

Montgomery, Douglas C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control. John Wiley & Sons,

2004.

"Teachings." The W. Edwards Deming Institute. Available from

http://www.deming.org/theman/teachings02.html. Retrieved on 12 May 2005.

Youngless, Jay. "Total Quality Misconception." Quality in Manufacturing. January 2000.

0

COMMENTS

Add your comment