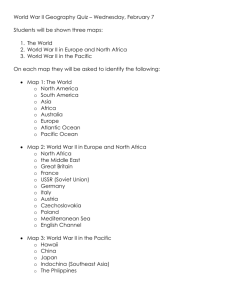

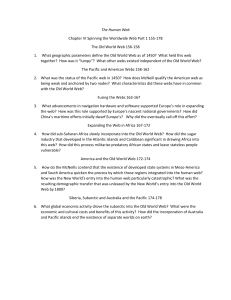

section iii. overview of conflict in the pacific

advertisement