paper - Command and Control Research Portal

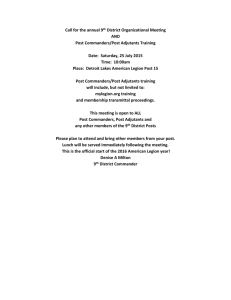

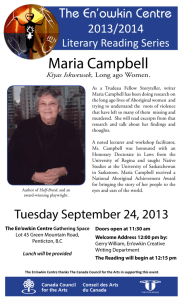

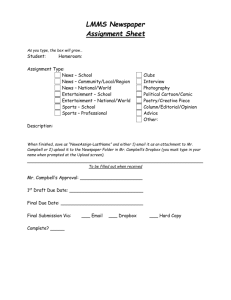

advertisement